By Sanjay Raman Sinha

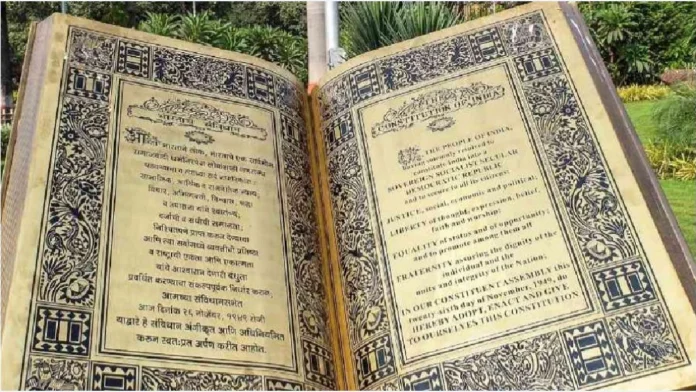

Once again, a familiar demand has found its way into national discourse: the removal of the words “secular” and “socialist” from the Preamble to the Constitution. This time, the call is louder and more coordinated, emerging from voices within the ruling establishment and affiliated ideological groups.

RSS General Secretary Dattatreya Hosabale fired the opening salvo, soon echoed by Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar—who labelled the inclusion of these terms “an insult to the spirit of Sanatan”—and Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, who dismissed them as alien concepts borrowed from the West.

Sarma argued that Article 14, which guarantees equality before the law, is sufficient to ensure constitutional parity. But this line of reasoning is both reductive and historically inconsistent.

EMERGENCY ORIGINS AND POLITICAL BAGGAGE

It is true that the words “secular” and “socialist” were not part of the original Constitution. In fact, Constituent Assembly member KT Shah repeatedly proposed their inclusion, but these amendments were rejected by Dr BR Ambedkar, chair of the Drafting Committee. Ambedkar, along with Jawaharlal Nehru, feared that enshrining “secular” explicitly might be interpreted as anti-religion, a risk they were unwilling to take in a newly partitioned and volatile India.

Eventually, it was during Indira Gandhi’s Emergency regime in 1976, via the 42nd Amendment, that the two terms were added. Alongside fundamental duties and other sweeping changes, the Preamble was updated to describe India as a “sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic”.

Despite the Emergency’s authoritarian excesses, the succeeding Janata Party government in 1977 chose to retain the amendment, indicating a tacit endorsement of its conceptual validity.

JUDICIAL SEAL OF APPROVAL

Over the years, the judiciary has repeatedly validated the inclusion and interpretation of these terms. In Kesavananda Bharati vs State of Kerala (1973), the Supreme Court held that secularism is a basic feature of the Constitution. The then Chief Justice of India SM Sikri’s view was unambiguous: Parliament cannot amend the basic structure of the Constitution, including the values expressed in the Preamble.

In Minerva Mills vs Union of India (1980), the Supreme Court reinforced socialism as an aspirational ideal, rooted in Directive Principles of State Policy. Most recently, in 2024, the Supreme Court again upheld the Preamble changes as constitutionally valid, provided they do not violate fundamental rights or the Constitution’s underlying structure.

BEYOND WORDS: THE POLITICS OF PRACTICE

While the legal debate is important, the more pressing question is how these ideals are implemented at the ground level. The Constitution does not define secularism or socialism; their meanings are inferred and actuated through policies.

If Congress-era socialism was Nehruvian in design and Indira Gandhi’s “Garibi Hatao” in spirit, the Narendra Modi government’s “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas” represents a contemporary variant—one that emphasizes inclusion, but within the framework of market-led reforms and majoritarian politics.

But the economic disparity persists. The top 10 percent of India’s population holds 77 percent of the national wealth, while the bottom 50 percent saw just one percent of wealth growth in 2017. This deepening inequality, combined with a growing fusion of state and religion, raises alarms about the relevance and application of these ideals—not just their mention in the Preamble.

THE ROAD AHEAD: LAW VS IDEOLOGY

Article 368 of the Constitution empowers Parliament to amend the Constitution, including the Preamble—but not at the cost of its basic structure. Any legislative move to delete “secular” or “socialist” could face judicial invalidation.

Ultimately, the conflict is not legal alone—it is ideological. It reflects a clash between visions of India: one that remains pluralistic and inclusive, and another that seeks to reframe nationalism through cultural and economic lenses.

As debates grow sharper and more politicized, what must not be lost is this: words matter—not just in law books, but in lived reality.

SECULAR ETHOS OF THE CONSTITUTION

Supreme Articles that embody secularism:

- Article 14: Equality before the law.

- Article 15: Prohibits discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth.

- Article 25: Freedom of conscience and religion.

- Article 26: Autonomy of religious denominations.

- Article 27: Prohibits taxes for religious promotion.

- Article 28: No religious instruction in state-run schools.

- Articles 29 and 30: Protect minority language, culture, and institutions.

SECULARISM AND THE COURTS

Judicial landmarks on secularism:

- St. Xavier’s College vs State of Gujarat

“There is no mysticism in the secular character of the State… no one shall be discriminated against on the ground of religion…”

- SR Bommai vs Union of India

“ …religious tolerance and equal treatment of all religious groups and protection of their life and property and of the places of their worship are an essential part of secularism enshrined in our Constitution… ”

- Ismail Faruqui vs Union of India

“It is clear from the Constitutional scheme that it guarantees equality in the matter of religion to all individuals and groups irrespective of their faith emphasizing that there is no religion of the state itself. The Preamble of the Constitution read in particular with Articles 25-28 emphasizes this aspect…”

- M Siddiq vs Mahant Suresh Das (Ram Janmabhoomi case)

“At its heart…the Constitution always respected and accepted: the equality of all faiths. Secularism cannot be a writ lost in the sands of time by being oblivious to the exercise of religious freedom by everyone.”