By Vikram Kilpady

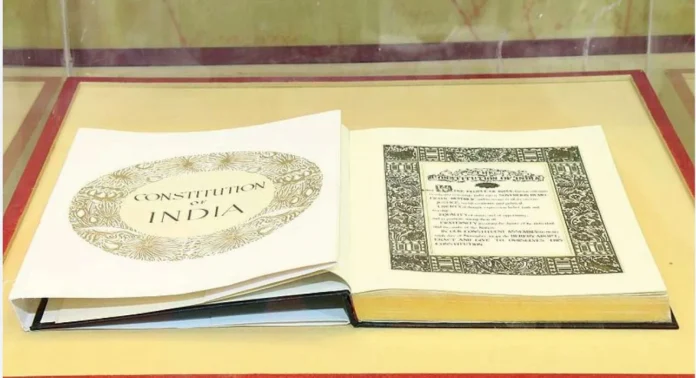

The Supreme Court recently laid to rest the controversy over the words “socialist” and “secular” added to the Preamble of the Constitution by the 42nd Amendment during the Emergency. The row was over the fact that the founding fathers who drafted the Constitution had not found it necessary to explicitly state the two foundational concepts by name in the Preamble, enacted in 1949. The two words were inserted under the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s express diktat.

The bench of Chief Justice of India Sanjiv Khanna and Justice Sanjay Kumar said “socialist” should not be narrowly interpreted as a restriction on the country’s economic worldview, but more as the State’s commitment to being a welfare state. “Neither the Constitution nor the Preamble mandates a specific economic policy or structure, whether left or right. Rather, ‘socialist’ denotes the State’s commitment to be a welfare State and its commitment to ensuring equality of opportunity. India has consistently embraced a mixed economy model, where the private sector has flourished, expanded, and grown over the years, contributing significantly to the upliftment of marginalized and underprivileged sections in different ways. In the Indian framework, socialism embodies the principle of economic and social justice, wherein the State ensures that no citizen is disadvantaged due to economic or social circumstances. The word ‘socialism’ reflects the goal of economic and social upliftment and does not restrict private entrepreneurship and the right to business and trade, a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(g),” the order said.

Justice Khanna recalled the recent majority judgment in the nine-judge Constitution bench in Property Owners Association and Others vs State of Maharashtra and Others, which said the Constitution allows the government to adopt a structure for economic governance that would subserve the policies for which it is accountable to the electorate. The Indian economy has transitioned from the dominance of public investment to the co-existence of public and private investment, the judge noted. Similarly, the order said “secular” should not be held to denote “opposed to religion”, as was the view of a few scholars and jurists during the Constituent Assembly debates in 1949.

“While it is true that the Constituent Assembly had not agreed to include the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ in the Preamble, the Constitution is a living document, as noticed above with power given to the Parliament to amend it in terms of and in accord with Article 368. In 1949, the term ‘secular’ was considered imprecise, as some scholars and jurists had interpreted it as being opposed to religion. Over time, India has developed its own interpretation of secularism, wherein the State neither supports any religion nor penalizes the profession and practice of any faith. This principle is enshrined in Articles 14, 15, and 16 of the Constitution, which prohibit discrimination against citizens on religious grounds while guaranteeing equal protection of laws and equal opportunity in public employment,” the order said.

“The Preamble’s original tenets—equality of status and opportunity; fraternity, ensuring individual dignity—read alongside justice—political, and liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship—reflect this secular ethos. Article 25 guarantees all persons equal freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion, subject to public order, morality, health, other fundamental rights, and the State’s power to regulate secular activities associated with religious practices. Article 26 extends to every religious denomination the right to establish and maintain religious and charitable institutions, manage religious affairs, own and acquire property, and administer such property in accordance with law. Furthermore, Article 29 safeguards the distinct culture of every section of citizens, while Article 30 grants religious and linguistic minorities the right to establish and administer their own educational institutions. Despite these provisions, Article 44 in the Directive Principles of State Policy permits the State to strive for a uniform civil code for its citizens,” the order said.

Addressing the challenges brought about by petitioners Dr Subramanian Swamy, Dr Balram Singh and Ashwini Kumar Upadhyay, the order said Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution allows it to make changes to the Preamble as well. One of the petitioners had argued that the tenure of the Fifth Lok Sabha (1971 to 1977) was extended by a year only for the duration of the Emergency, and that it did not enjoy the will of the people to make such changes to the Constitution, leave alone to the Preamble. Further, the petitioners had challenged whether the Preamble can be amended in 1976 retrospectively with effect from November 26, 1949 and on behalf of the Constituent Assembly, which no longer existed in 1976.

Delving into the petitioners’ arguments, the order said they do not require detailed adjudication as the flaws and weaknesses in the arguments are obvious and manifest. “These amendments were made in 1976. Article 368 of the Constitution permits amendment of the Constitution. The power to amend unquestionably rests with the Parliament. This amending power extends to the Preamble. Amendments to the Constitution can be challenged on various grounds, including violation of the basic structure of the Constitution. The fact that the Constitution was adopted, enacted, and given to themselves by the people of India on the 26th day of November, 1949, does not make any difference. The date of adoption will not curtail or restrict the power under Article 368 of the Constitution. The retrospectivity argument, if accepted, would equally apply to amendments made to any part of the Constitution, though the power of the Parliament to do so under Article 368, is incontrovertible and is not challenged,” the order said.

CJI Khanna said during the debates in Parliament on the 44th Amendment, the inclusion of secular and socialist by the 42nd Amendment came under scrutiny. “The word ‘secular’ was explained as denoting a republic that upholds equal respect for all religions, while ‘socialist’ was characterized as representing a republic dedicated to eliminating all forms of exploitation—whether social, political, or economic,” the order said. Noting the fact that “socialist” and “secular” have achieved widespread acceptance, with their meanings understood by “We, the people of India” without any semblance of doubt, the bench reiterated that the petitions filed in 2020, 44 years after “socialist” and “secular” became integral to the Preamble, makes the prayers particularly questionable.

Secularism has been, in fact, held to be a basic feature of the Constitution by the Supreme Court itself in many landmark decisions, the bench said. Listing the Kesavananda Bharati judgment, the SR Bommai judgment and the Ismail Faruqui verdict, the Court elaborated that the expression “secularism in the Indian context” is a term of the widest possible scope. The State maintains no religion of its own, all persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience along with the right to freely profess, practice and propagate their chosen religion, and all citizens, regardless of their religious beliefs, enjoy equal freedoms and rights.

The bench observed: “In RC Poudyal, the Court elucidated that although the term secular was not present in the Constitution before its insertion in the Preamble by the Constitution (Forty-second Amendment) Act, 1976, secularism essentially represents the nation’s commitment to treat persons of all faiths equally and without discrimination.” Referring to practices like untouchability, the court noted, “…the ‘secular’ nature of the State does not prevent the elimination of attitudes and practices derived from or connected with religion, when they, in the larger public interest impede development and the right to equality. In essence, the concept of secularism represents one of the facets of the right to equality, intricately woven into the basic fabric that depicts the constitutional scheme’s pattern.”

Socialist and secular in the Preamble have long been bugbears of the right wing. Secularism was lampooned and packed away as “pseudo-secularism”, and socialism was generally dismissed as a fossilised Cold War appendage. That, however, doesn’t prevent right-wing political parties from loosening their purse strings via Direct Benefit Transfer a few weeks ahead of the model code of conduct coming into force, like in Maharashtra, where a seemingly patchwork group pulled off a near impossible landslide. Like “secularism in the Indian context”, socialism in India is best served in the shape of doles, as the State cannot afford to take chances with its rambharose economic model. Much as we ape China, poorly at that, and pit ourselves against it, the inability of politicians and policy makers to devise a cogent economic model—a framework that would ensure a decent disposable income, capable of both letting the masses keep demand growing and holding inflation under check—will only see more handouts, while India cements itself as a middle-income economy. Then we can wonder about this year’s unsold cars and motorcycles during the usually ebullient festive season.