On the occasion of the 75th birthday of the apex court, the chief justice has rightly called for introspection on a number of issues, including long court vacations, adjournment culture and lengthy arguments which delay judicial outcomes

By Sanjay Raman Sinha

“The old order changeth, yielding place to new.”

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson, poet

Diamond Jubilees are occasions for assessments and appraisals, for meditation, soul searching and blueprinting. As the Supreme Court turned 75, the celebratory gathering in the Court premises was attended by the chief justice and the prime minister.

On the occasion, Chief Justice DY Chandrachud called for introspection and to take note of the “challenges threatening the relevancy of the court as an institution” and begin “difficult conversations” starting with the necessity to continue with long vacations. “Let us begin the conversation on long vacations and whether alternatives such as flexi-time for lawyers and judges are possible,” he said.

The long vacations of the judiciary have always been criticised. When compared to the backlog of mounting cases and a slow, long winded judicial system, it is no wonder that there are critics of these vacations. The summer and winter holidays are an annual ritual which the Britishers bequeathed the Indian court system.

The Supreme Court on an average clocks 214 workdays per year. The summer vacation accounts for 45 days, winter vacation 15 days and Holi holidays are for a week. During Dusshera and Diwali, the Court closes for five days each.

As per the official statement of the law minister given on the floor of the House, the average number of working days of the Supreme Court was 224 days in 2019, 217 days in 2020 and 202 days in 2021.

On December 15, 2022, Law Minister Kiren Rijiju on the floor of the Upper House raised objections to the long vacations of courts saying they hamper the justice delivery system.

Supreme Court Rules, 2013, state “period of summer vacation shall not exceed seven weeks and the length of the summer vacation and the number of holidays for the court and the offices of the court shall be such as may be fixed by the Chief Justice and notified in the official Gazette so as not to exceed one hundred and three days”. The rules stipulate a maximum of 103 holidays, but the yearly average of vacations works out to 151 days. However, despite these vacation figures, the Supreme Court has a higher number of sitting days in comparison to apex courts of other countries.

The judiciary has its own reasons for justifying long leaves. A judge has long working hours, has to study cases prior to hearings and write judgments. Their stress levels are also high.

Justice Bhanwar Singh, former judge of the Allahabad High Court, told India Legal: “In fact, in district courts, the provisions for leave are not all that objectionable. Judges have to do lots of brainwork and hence, they need rest and recreation. In district courts, the same provision for leave and holidays must continue. As far as High Courts and the Supreme Court are concerned, a little cut in holidays can improve the situation. For example, in the Supreme Court, instead of a seven-week vacation, there could be four weeks only. Likewise, in High Courts, instead of four weeks, it should be reduced to three. There can be a little rationalisation in case of holidays and leave.”

The Justice Malimath Committee, set up in 2000, had suggested that the leave period should be reduced to 21 days to take care of pendency. It had suggested that the Supreme Court should work for 206 days and High Courts for 231 days every year. In 2009, the Law Commission of India had suggested that the holidays should be reduced to at least 10 to 15 days and court working hours should be increased by at least half an hour.

Various chief justices have also tried to streamline the vacation system of the apex court. In 2014, Chief Justice RM Lodha had suggested keeping the Supreme Court, High Courts and trial courts open throughout the year. Former Chief Justice TS Thakur had suggested holding court during holidays, if parties and lawyers mutually agreed.

Today, if Chief Justice Chandrachud revisits the issue with concern, a rethink in the vacation policy should be on the cards. However, without a concomitant change in legal processes and court proceedings and without a coherent meeting of minds of all concerned, this reform move won’t take off.

Justice Vimlesh Shukla, former judge of the Allahabad High Court, told India Legal: “Vacations which can be referred to as long are the summer ones. This can be curtailed by four weeks keeping in view the large scale pendency. Alternatively, the chief justice of India (CJI) or chief justices (CJs) of High Courts can ask judges to give an option for their sitting during vacations. Instead of vacation judges, the services of half of the strength of judges should be utilised. The CJI and CJs should consult brother judges and take their opinion and consent before effecting vacation changes.”

Another idea which the chief justice tossed was “whether alternatives such as flexi-time for lawyers and judges is possible”. Flexible timings for court hearing is possible option in order to tie the loose ends. A special day for specific types of hearings is another option.

So how many vacations do courts abroad have? The Supreme Court of the United States has argument days where only oral submissions are admitted. There are non-argument days where verdicts are read out and there are conference days where the judges discuss cases in private. These are spread over the total working days.

In many nations, the Supreme Courts observe a term-based system of hearing. The Australian High Court allocates two weeks per month for hearing arguments. The United States Supreme Court hears arguments for about five to six days each month. Such arrangements can be adopted in India with suitable modifications.

Evening courts have become a reality in India. Many function in the evenings after the regular hours and handle specific cases. In Delhi, evening courts operate in Dwarka, Rohini and Tis Hazari district courts, among others. With online hearings in vogue, off hour courts can be conducted conveniently. As these will stretch the court hours, the roster has to be organised in a judicious manner.

Justice Bhanwar Singh suggested: “The number of judges should be doubled as with the same infrastructure they may sit in two shifts—one morning and the other, evening. With this increase in strength, the government will not be burdened with infrastructure. Criminal courts may sit during the day, while in the second shift, civil cases may be heard till 8 pm. This is a solution under the flexi-time option. In the long run, the number of judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts may also be increased and accommodated in two shifts.”

Chief Justice Chandrachud also underlined the need to “emerge out of adjournment culture”. The issue of frequent and unplanned adjournments was addressed by the Supreme Court registry in December, where it had mandated the discontinuation of the practice of circulation of adjournment slips. Subsequently, the Supreme Court Bar Association (SCBA) and the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association raised concerns over circulars. Further to the furore, the Supreme Court had constituted a committee of judges for preparing a standard operating procedure for lawyers seeking adjournment of proceedings. While the SCBA had contested for legitimate grounds for seeking adjournments, the CJI had different reasons for his concern over adjournments. He had urged lawyers to not treat the Supreme Court as a “tarikh-pe-tarikh” court.

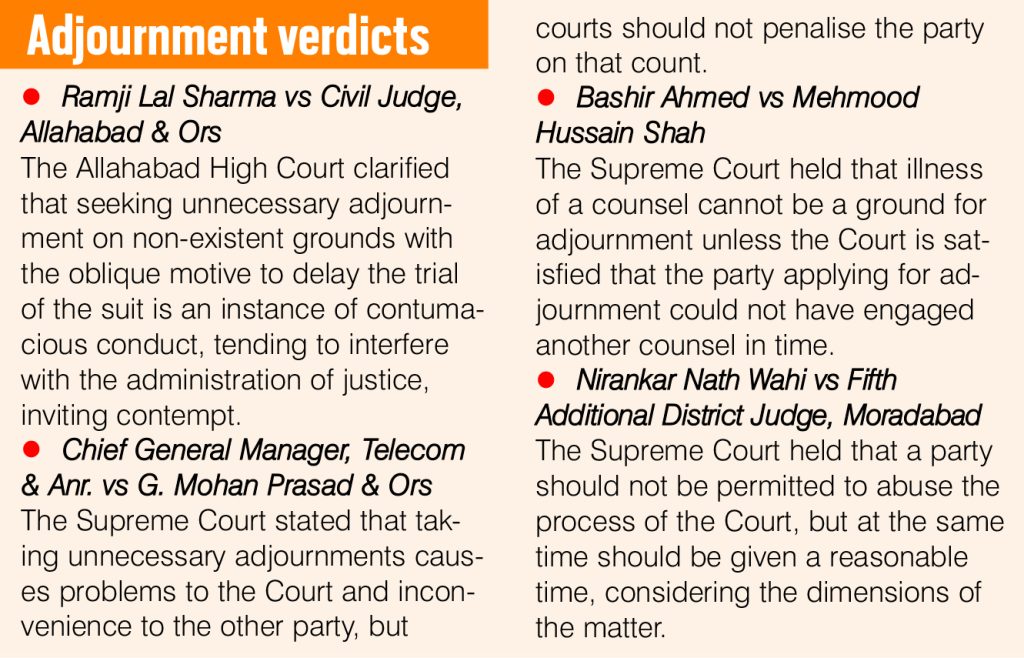

Adjournments are used to temporarily defer court proceedings for a reason. It is the discretion of the judge to issue them. If the parties fail to appear, then also an adjournment is resorted to. However, adjournments without significant reason can negatively impact case proceedings and cause delay. Unsubstantial or frivolous reasons for adjournment feted out by parties makes them liable to penalties. Keeping this in mind, the chief justice has cautioned against the indiscriminate practice of adjournment via slips. In fact, there are many verdicts where the apex court had cautioned against indiscriminate adjournments (see box).

Justice Vimlesh Shukla opined: “The Court may, if sufficient cause is shown, at any stage of the suit, grant time to the parties, and may from time to time adjourn the hearing of the suit for reasons to be recorded in writing. However, adjournment cannot be sought by a litigant in a routine manner. It must be a bona fide attempt, on behalf of the party.”

The chief justice was also concerned about lengthy oral arguments, which go on for days, delaying judicial outcomes. The practice of long arguments can be curtailed by setting timelines for them. In recent times, the Supreme Court has instructed the parties in many cases to adhere to timelines and set out argument schedules too. Written submissions can also curb long arguments. However, arguments are opportunities for the judges to ask questions directly to the counsels and clarify points.

Chief Justice Chandrachud also called for a level playing field for first generation lawyers. This is a recurring lament of these lawyers. With no godfather in the profession, they find it hard to gain a foothold and learn their trade effectively. The imbalance of privilege and opportunity is inherent in the dynamics and power structure of the law profession. It’s a field where personal linkages count as much as experience and legal acumen. How to set straight this imbalance is the moot question. This may demand shrugging off vested or personal interests for a more common good. But can the era of “elite men” be so easily be wished away?

Finally, the chief justice highlighted the changing demographics in the legal profession. “Men, women and others from marginalised segments have the will to work and the potential to succeed. Women, traditionally under-represented in the profession, now constitute 36.3% of the working strength of the district judiciary.” Women in black have definitely increased in numbers. The Supreme Court bench currently has three women judges.

In December, the chief justice had constituted an all-woman bench comprising Justices Hima Kohli and Bela M Trivedi to adjudicate transfer petitions involving matrimonial disputes and bail matters. This was the third such all-women judge bench in the Supreme Court history. The average tenure served by women judges is 4.3 years. This is a year less than the average tenure of all the judges in the Supreme Court. Clearly, it is not only the entry of women that matters, but also upward mobility. The glass ceiling may have been broken, but many need to go up through it.

All said, on the 75th anniversary of the Supreme Court, the progressive thoughts of the chief justice aptly resonate with a call for “difficult conversations” with the status quo.