By Binny Yadav

“Let us remember: one word may kindle a fire, another may quench it.”

—George Eliot, Middlemarch

In the solemn chambers of law, where every word defines rights, duties, and destinies, George Eliot’s warning reverberates anew. The Supreme Court in Zoharbee & Anr vs Imam Khan (D) Thr. LRs & Ors, recently delivered a stern admonition: “Linguistic precision is not a procedural formality—it is a substantive necessity in judicial work.”

The case, rooted in a property dispute under Mohammedan Law, revealed a fault line that runs deep in India’s judicial system. The apex court found that an English translation of a trial court’s judgment—originally written in a regional language—was so poorly executed that it distorted the facts and reasoning. The appellate court, relying on that flawed translation, had struggled to understand the case itself.

The result, the bench of Justices Sanjay Karol and Prashant Kumar Mishra warned, was not merely inconvenience—it was an erosion of justice.

WHEN WORDS FAIL JUSTICE

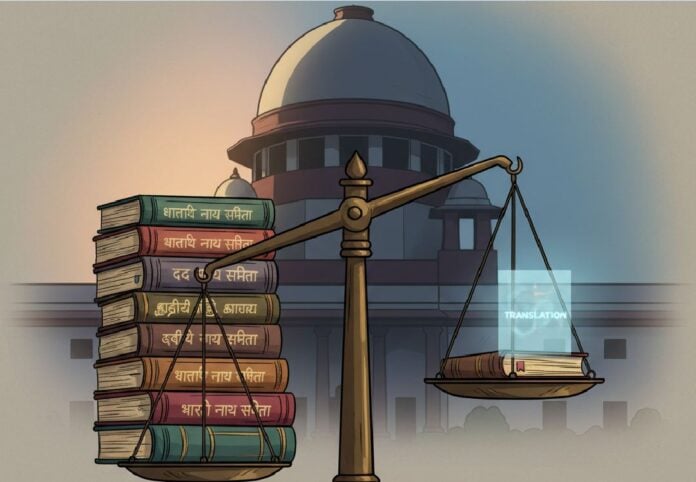

In India’s judicial hierarchy, where lower courts function in local languages and higher courts in English, translation serves as the fragile bridge between fact and finality. When that bridge cracks, justice falters.

As the Supreme Court put it: “Every word, every comma has an impact on the overall understanding of the matter.”

The Constitution foresaw this challenge. Article 348 mandates English as the language of higher courts, yet allows states—with presidential assent—to use regional languages. However, every such judgment must be accompanied by an authoritative English version under Section 7 of the Official Languages Act, 1963. Translation, therefore, is not a courtesy—it is a constitutional and procedural necessity.

TRANSLATION ON TRIAL: PAST PRECEDENTS

The Zoharbee case is not an anomaly. Courts have repeatedly struggled with mistranslations and their legal fallout:

- Faulty Translation Costs Rs 25,000 (2016): The Supreme Court fined a petitioner for submitting an incomprehensible translation of a Hindi High Court order, lamenting that the bench had to “struggle for one hour to figure out the sense of the order”.

- English Prevails in Conflicts (2025): The Allahabad High Court ruled in Maya Shukla vs Secretary/Examination Controller that, in case of conflict, the English text of a statute prevails—a reminder that linguistic inconsistency can warp legislative intent.

- AI in Action: High Courts such as Kerala, Delhi and Orissa now use the Supreme Court’s SUVAS AI tool to publish vernacular translations. Yet all explicitly declare the English version as binding—an acknowledgment that inclusivity must not come at the cost of precision.

A SYSTEM BETWEEN PROMISE AND PERIL

By 2025, the Supreme Court had translated over 36,000 judgments into Hindi and nearly 47,000 into other regional languages—an impressive leap towards democratizing access.

But the process remains fraught. Machine translations often stumble over legal idioms, cultural nuances, or syntactic ambiguity. A mistranslation like turning “held by the defendant” into “held for the defendant” can invert the very meaning of a property ruling.

Such errors, experts warn, are not rare—they are systemic. They threaten not only procedural correctness, but the very right to fair hearing. As the Court itself has noted, the right to understand a judgment in one’s own language is part of natural justice.

BRIDGING THE GAP

To address this crisis, the Supreme Court has created an AI-Assisted Legal Translation Advisory Committee to oversee work done through SUVAS and the e-Courts platforms. Yet, accuracy in AI-driven translation hovers around 15-20 percent without human review.

The human translators, underpaid and often undertrained, bear the burden of converting dense legal reasoning into clear and faithful text—a task demanding both linguistic and legal mastery.

Despite the scale of India’s judicial machinery—handling over 50 million cases—there is still no dedicated institutional mechanism for translation quality control. The absence of such linguistic infrastructure is a silent administrative shortfall that now demands urgent reform.

THE VERDICT BEYOND THE CASE

The Zoharbee judgment, then, is more than a reprimand—it is a call for introspection. India’s multilingualism is not an inconvenience; it is a constitutional reality. Ensuring linguistic accuracy is not about semantics or pride—it is about the integrity of justice itself.

In the end, as the Supreme Court reminded, “the spirit of a judgment lies not just in the words chosen, but in how faithfully those words are conveyed across languages.” Translation, therefore, is not a clerical act—it is an act of justice.

—The writer is a New Delhi-based journalist, lawyer and trained mediator