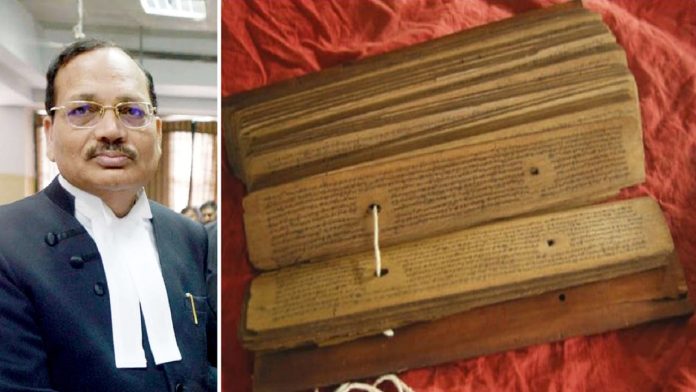

By Justice Kamaljit Singh Garewal

On the edge of the village is a small pond, on the banks of which grows a peepul tree. The village elders would gather under its shade in summer months to meet and exchange stories. Shepherds and cowherds brought their flock to drink water from the pond. Children frolicked mischievously on the flat ground nearby, watched over by their grandfathers. This was the typical scene from times immemorial. It was our rural idyll.

The peepul tree is centuries old and has watched the march of invading armies, seen the young set off to defend their country. After one lot of invaders was replaced by another, more sophisticated and better organised young men joined them to defend their Empire. But a band of fighters took up non-violence as the path to win freedom back. The peepul tree watched the transition to Independence, with great expectations. Inevitably, development came and machines began to plough the farm lands in the name of progress. The peepul tree too was cut down, while the pond got filled up and dried. With this advance of pseudo modernity, the centuries-old village life also slowly came to an end. The destruction of traditional village and small town life was now complete and our traditional ethical values were put in jeopardy.

The children who played on the grounds near the pond have grown into mature men and got married, but their children’s playgrounds have shrunk. They now have laptop screens to play their games. Only a few can be seen on the playing fields and from among them, some develop into sportsmen at the district, state or national level. The village elders of the 1930s and 1940s, though, have moved on. Is the rustic ethical life and standards of morality, inherited from the past, still with us even in small measure?

Sometimes in the village when a man was murdered or a child abducted or a woman molested, the elders would say that this was something very bad (bahut bura hua), and add that this should never have happened in their village, where everyone lived in a spirit of bhaichara (brotherhood). A strong denouncement of the perpetrators and their act and a clear statement of positive ethics. Sadly, the ethical voice now gets drowned in a myriad legal ways through which the perpetrators try to escape the clutches of law and sometimes, even punishment.

Therefore, the Indian Ethic must be examined, defined, applauded and re-enforced. It has been written into our DNA, in the Constitution and laws, it is practised in homes, schools, colleges, work places and in public life. But the danger we are facing as a nation is the weakening of ethical standards and basic morality. Our timeless bhaichara must be strengthened by stopping inter-faith competition and casteism. In its place, we should develop rational humanism and universal brotherhood of man, and respect the dignity of each individual. This is the true Indian Ethic.

The concept of morality was the subject of a recent talk delivered by Justice Surya Kant of the Supreme Court. He was speaking at Kurukshetra on Resurgent Bharat: Changing Contours of Law and Justice. He discussed how our legal system had evolved, and hailed India’s decision to supply Covid-19 vaccines to 80 other nations that could not have accessed it, and termed it an example of constitutional morality.

Discussing the evolution of our legal system, Justice Surya Kant said: “The evolution of our legal system does not begin with our liberation from British Rule, but it pre-dates Independent India. It is an accepted view among scholars that India had a form of legal system and structure even during the bronze age and the Saraswati Sindhu or the Indus Valley Civilisation. The most authoritative and famous text that lays out the uniquely Indian way of viewing law, politics, domestic and international affairs is Kautilya’s Arthashastra.”

Justice Kant further said that he was not advocating any particular principle or rule of law which was prevalent in ancient India, but it was certainly not something that we got from the Britishers. “We had a very rich heritage and that heritage is reflected from the very meaning of the word arthashastra, which conveys the intent behind all-encompassing Rules of Nature. In simple terms, Kautilya’s objective was to bestow upon us his understanding of the science of all things, whether they be economic trade or wealth, social polity and unity and administration of justice and law. It is our very own magnum opus on how to run a fully functioning State and is considered to be one of the earliest works of legal realism.”

Kautilya’s Arthashastra is our peepul tree. It was a treatise written about 2,400 years ago as a practical guide for kings, his ministers and officials. It covers every conceivable subject under the sun which still has relevance in modern administration and governance. The book is a masterpiece of topics like statecraft, politics, military warfare, law, accounting, taxation, fiscal policies, civil rules, internal and foreign trade, etc. Arthashastra must be studied and its principles followed by men and women in public life like judges, administrators, military and police officers, economists and planners. But guidance from this ancient text cannot help much in governance if we lack basic ethics.

Returning to real-life India, we see people flouting even traffic rules. At a railway level crossing, one sees impatient drivers overtaking waiting cars to get ahead. At bus stands, many refuse to form a queue to wait for their turn to be attended by the booking clerk. People seem to think that a push and a shove can help them get ahead quicker. Basic ethics have vanished. People carelessly throw household garbage on the roads. Many a time, unethical behaviour takes a serious turn, particularly when no one is watching, no one else knows and no one will tell. Giving and accepting bribes, concealing the real value of sale/purchase of land or a used car when only a part of the price is paid through a bank. And what about our open and blatant sifarish culture when connections are used to get a job, a posting, a promotion?

One of the most serious incidents which tested our ethics was the year-long farmers’ agitation of 2020-21. Three laws were passed by Parliament, supposedly for the benefit of farmers and agrarian economy. Farmers of the farming belt of North India organised themselves and registered their protests because they were the best judges of the benefits which the laws were promising to deliver to them. Therefore, the agitation was ethically and morally justified. But negotiations with government ministers did not make any progress in spite of a dozen meetings. Finally, the agitation involved hundreds of thousands of protesters, who camped under freezing conditions, faced cold winds, hot sun, dust storms, rain and all kinds of privations and hardships. After loss of hundreds of lives, the protest finally came to an end when the laws were all of a sudden withdrawn. The question which arises is this: which side was acting ethically and which was acting legally? How should one strike a balance between ethics and law? Was it kisan bhaichara v. the rest? Sadly, the much needed reforms have taken a back seat. Whereas ethics and morality should have been in the forefront to prevent such confrontations, the cost to the nation has been too dear to bear.

On ethics, one should draw guidance from the Constitution itself. The Preamble is the most outstanding provision which lays down principles of ethics. Next in importance are the Directive Principles of State Policy and Fundamental Duties. Many issues of enforcement of rights against the State, which take up so much judicial time and resources, would be otiose if handled by the State in an ethical and fair manner, in the first place. We know that this does not happen. As a result, the judiciary has to discharge an extraordinarily heavy burden.

The Indian situation on the subject of ethics remains very ambivalent, to say the least. In the ultimate analysis, ethics cannot be inculcated in the people of India without proper role models at all levels, starting from parents at home and school teachers at school. Ethics is not something which can be legislated upon. The Constitution shows us constitutional morality, but it is for the People of India who must follow the path and bring ethics and morality into their daily lives, at least in public affairs. The village elders under the peepul tree had an ethical message to convey for future generations, but they have passed on and the tree has been uprooted. Our selfish, self-centered, consumer-driven, materialistic people have put the Indian Ethic under serious challenge.

—The writer is former judge, Punjab & Haryana High Court, Chandigarh and former judge, United Nations Appeals Tribunal, New York