By Sujit Bhar

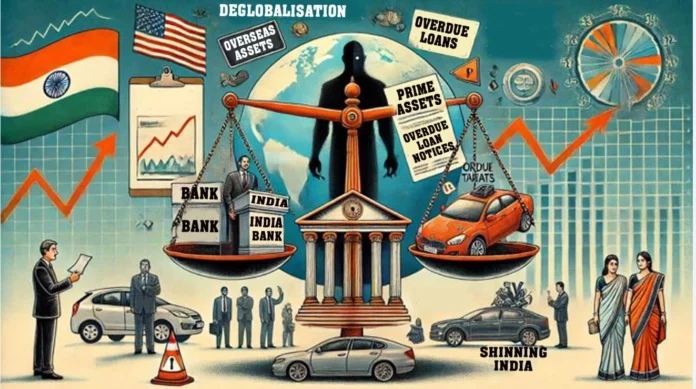

International financial scenarios present rather interesting paradoxes. While news of Americans falling behind on car payments at a record pace seems disturbing, bringing back memories of the 2008 subprime crisis, in India, even with its banking sector’s baggage of massive non-performing assets (NPAs), recent trends indicate a significant improvement. The gross NPA ratio declined from a peak of 11.5 percent in March 2018 to 3.9 percent in March 2023, reflecting enhanced asset quality and effective regulatory measures.

This is happening while, as per Fitch Ratings data, almost 6.6 percent of subprime auto borrowers in the US, those with poorer credit scores and greater financial risk, were at least 60 days behind on their car loans in January 2025, as per a report in the Daily Mail.

This is also happening while Southeast Asian nations are exhibiting tendencies towards what is being called “deglobalization”, characterized by increased protectionism and a focus on strengthening domestic industries.

So what is India doing right, within this significant shift that the global economic landscape is undergoing? This probably can be understood by the quality of assets that have gone into NPAs in the books of banks. This, probably, can also be understood in the declared quality of such assets. Those assets were mostly categorised as class A and above, deserving prime lending rates or lower. Those were assets that were preferred. Very few among such assets were so-called “sub-prime” in India.

On the other hand, India’s stance in the world financial order today is indecisive. There is no clear stance visible that defines India’s international economic dealings. All financial agreements of late, including the one that has seen tariffs on in the import of EVs into the country being slashed from over 100 percent to a mere 15 percent—this happened mostly due to pressure from Elon Musk the head of Tesla, and from US President Donald Trump—tend to disrupt any established financial policy that had been developed over years by economists. In an era of deglobalisation, India seems to be racing in the opposite direction.

The question is whether all these will benefit India. Trade relations with the US are extremely important for India, hence this may be seen as a good move. However, the recent rally back in the Indian stock markets notwithstanding, dealers have not shown much trust in the quality of Indian stocks, as Foreign Portfolio Investors started to pull out.

So, how has the Indian economy seemingly sidestepped a recession, as of now? That, too, seems to be in the quality of assets under consideration. As noted before, the quality of assets that went into NPA, were mostly classified as prime. Indian banks have learnt not to involve themselves with lower or the so-called subprime sector. While the loan disbursement rate has fallen, even Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has accepted that the prime reason for the faltering and virtual decimation of the Indian MSME sector is lack of funds. Yet, while the government does allocate funds to be loaned out to this sector—this is specifically important for the micro sector, which once involved the most people in employment within the economy, despite being the unorganised sector—the disbursement has been selective.

It is a matter of common sense that lenders would approach those who can repay. The social development facade has finally been stripped away, leaving those who desperately need funds in the lurch, with money flowing into coffers that may have survived without it for a while longer. The effect of this is a steady fall in employment, a decrease in wealth creation, and the creation of a freebie-dependent society, one that believes in the right to survive without the preceding clause of productive activity.

Even within this sanitised atmosphere, there have been disasters. The Reserve Bank of India’s recent crackdown on retail loans, for example, has slowed credit growth, impacting banks’ earnings and leading to increased bad debts. Major banks have reported surges in provisions for bad loans and deteriorating asset quality, prompting more cautious lending practices.

And let us remember that this is within an ecosystem that has been synthetically sanitized to exclude any entity that even remotely looks sub-prime. At the same time, Moody’s has affirmed that Indian banks and non-banking financial corporations (NBFCs) are well-positioned to withstand global banking sector stress, supported by strong domestic demand and improved credit conditions.

That brings us to the domestic demand issue. A recent study has exposed the size of the real middle class in India and the lack of depth of that is scary. The study has suggested that about a billion Indians today do not have the capacity to spend more than what is needed for basics. That leaves no more than 400 million Indians, of who half would be children. The total purchasing power of India lies in a very shallow pool, and whatever Moody’s has found out seems like a mirage in a desert.

So what is the way forward for India? In light of global deglobalization trends, India faces the challenge of balancing protectionist policies with the need to remain integrated into the global economy. Striking this balance is crucial to ensure sustained economic growth without isolating the country from beneficial international trade relationships.

That is easier said than done, but these are tough times and tough decisions are warranted.