By Sujit Bhar

The 2023-24 Union budget was unique in some ways, while pretty much like many more in others. As the proposals sink in, it dawns on one that even with next year’s general elections staring the NDA in the face, and even with nine elections lined up for this year itself, populism wasn’t the prime mover this year. That’s unique, though not fair. And it fails to stand out among the rest, because it still remains indifferent to the fate of the poor of the country as Union budgets have always been.

The big, drumbeat news was the huge growth (33%, to Rs 10 lakh crore) in capex for infra. This will, in turn, force the government to go into borrowings. Borrowings and liabilities make up 34% of the government’s receipts. The Goods and Services Tax (GST) contributes 17%. A projected fiscal deficit of 5.9% might be overshot.

There is a rather dark side to this drumbeat announcement. The fact that the government has had to go into a further infra capital expenditure also means that the private sector has its purse strings tied up and is not investing. That has left the government to try and pick up the slack, which is a clear admission to failure by the government on this front and it becomes imperative to look into why the private sector remains apathetic to go into investment mode.

Forget the Gautam Adani issue, because that cropped up pretty late. If the private sector has not been ploughing back its profits, or has not opened up its reserves, it means there is something seriously wrong with the state of governance in the country and/or that the private sector’s own market projections must have been grim.

Last August, the RBI had admitted that loan off-takes have not been up to expected levels. Data on the table also pointed at suboptimal capacity utilisation. At that time, the RBI had pointed out that while it expected private-sector capital expenditure (capex) to lift off in the quarters ahead, data showed a sad picture in the preceding years. The pandemic years’ inactivity remains a massive excuse for the government, but while growth was supposed to shoot up thereafter (with the new baseline making balance sheets looking healthier), that did not really happen.

The RBI last year admitted that though the envisioned total project cost of Rs 1.43 trillion almost doubled in contrast with the record low of Rs 75,558 crore in 2020-21—that is the new baseline effect—it still remained lower than pre-Covid levels. It is below the Rs 4 trillion annual loans sanctioned for projects since the glory days of corporate investment in 2010-11.

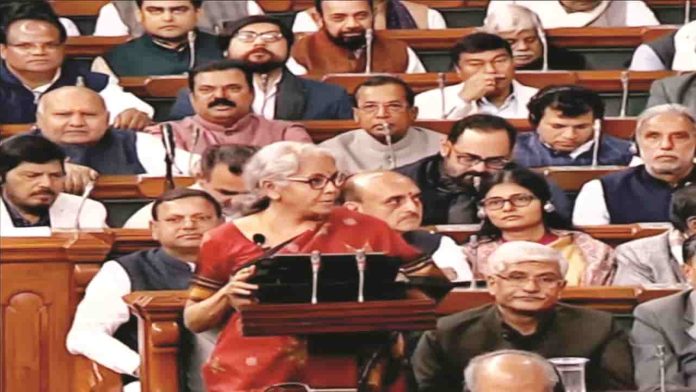

The second shady part is that while Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman stuck to a stated development agenda, which is a good optic, everybody knows that the trickledown fable that economists construct out of major infra proposals has always remained only in fairytale books in India. Huge development projects have a way of becoming self-serving events in themselves. Benefits never reach the marginalised in a sustained way.

The country is seeing growth, for sure, but this growth has mostly distanced itself from employment. India needs blue-collar employment in the long run. India needs its MSME sector—devastated through demonetisation and Covid—to be resurrected. If those sound populist measures, then so be it.

India also needs proper and timely goods movement and a fair payment structure in the farm sector, India’s largest employer. Contrast this to the mammoth infra capex, and we get a picture of a skewed development agenda that fails to identify the real disease, and treats symptoms instead.

Consider the theory of loans to MSMEs. To put it simply, a loan is required by a firm to service an order, to buy raw materials, for operational costs, to pay the workers and for incidentals. The bigger problem lies elsewhere, in the two sections of procuring orders and then ensuring payments. Without these, the very purpose of the loan is defeated. The same applies to the farm sector. Hence, if the government acts as a catalyst in order procurement, timely payments as well as the loan, these sectors can slowly come back to health.

The finance minister declared the Vivad Se Vishwas scheme for failing MSMEs. It says that MSMEs will receive 95% of the performance security from the government under this scheme in cases of failure to execute contracts. As explained above, this is the second part of the MSME medicine dose. The contract has to materialise in the first place.

These days, small businesses and the farm sector are living off their savings. The savings will not last, neither would the small entrepreneur or their employees, however long and wide new expressways are, or however modern the ports may be.

The focus, therefore, was never the poor; it never is. Capex sounds big; it sounds good in an election year. But, maybe populist would have sounded more real.

—The author writes on legal, economic and corporate issues, apart from social commentary. He is Executive Editor at India Legal