By Dr Swati Jindal Garg

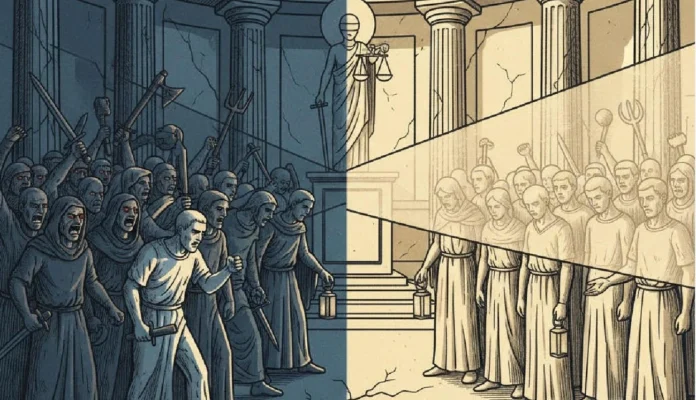

Mere presence at a crime scene involving a mob does not automatically make one a participant in the “unlawful assembly”. This crucial clarification came from the Supreme Court in the case of Zainul vs State of Bihar, setting a precedent that safeguards innocent bystanders from wrongful criminal liability.

A bench, comprising Justices JB Pardiwala and R Mahadevan, delivered the judgment, underscoring that guilt under Section 149 of the Indian Penal Code arises only when a person shares the common object of the assembly—not simply because they were present at the scene.

Justice Pardiwala, writing for the bench, laid down seven key parameters to determine criminal liability in such cases:

1. Time and place of the assembly’s formation.

2. Conduct and behaviour of its members near the scene.

3. Collective conduct of the group versus individual actions.

4. Motive behind the crime.

5. The sequence in which the incident unfolded.

6. Nature of weapons used.

7. Type and extent of injuries inflicted.

“Mere presence at the scene does not ipso facto render a person a member of the unlawful assembly unless it is established that such an accused shared its common object,” the Court held. “A bystander, to whom no specific role is attributed, would not fall within the ambit of Section 149,” the Court ruled.

The ruling came in response to an appeal filed by ten convicts from Katihar, Bihar, who had been charged under Sections 302 (murder) and 149 (unlawful assembly) after a 1988 brawl over paddy harvest resulted in two deaths. The Supreme Court found serious inconsistencies in the investigation, doubting the “genuineness of the FIR” and noting that the prosecution’s evidence failed to distinguish passive onlookers from active participants.

As a result, all ten were acquitted, with the Court emphasizing that mass trial cases demand utmost judicial caution to avoid miscarriages of justice.

The bench added that courts must look for credible evidence that an accused shared the unlawful assembly’s objective before convicting: “It is safe to convict only those whose presence is consistently established and to whom overt acts are attributed in furtherance of the common object,” the judgment observed.

By laying down these parameters, the apex court has effectively erected a legal safeguard against convicting those who may have been “in the wrong place at the wrong time”.

While reaffirming the doctrine of constructive liability under Section 149, the judges cautioned that its application must be tempered with prudence. The seven-point test now serves as a guiding framework—ensuring that justice distinguishes between those who act and those who merely witness.

—The author is an Advocate-on-Record practising in the Supreme Court, Delhi High Court and all district courts and tribunals in Delhi