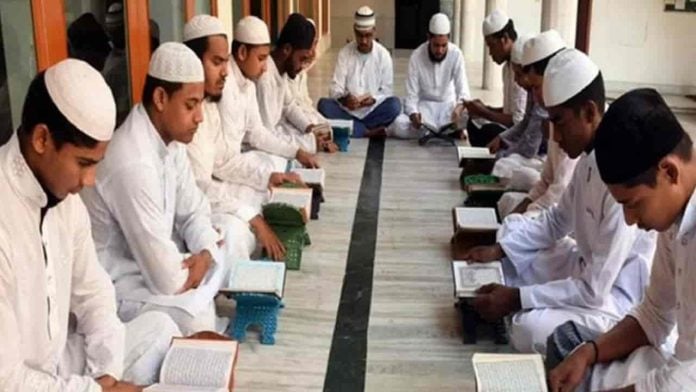

The apex court recently stayed an Allahabad High Court order that had declared the Madarsa Act “unconstitutional”. A look into the Act per se, the orders and how much worthwhile education was really being imparted

By Sujit Bhar

The case over the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004, is far from over. The Supreme Court recently stayed an Allahabad High Court order that had declared the Act “unconstitutional” on the ground that it violated “the principle of secularism” and fundamental rights provided under Article 14 of the Constitution.

The arguments presented by the top court bench of Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud and Justices JB Pardiwala and Manoj Misra included the following (verbatim):

- “We are of the view that the issues raised in the petitions merit closer reflection.”

- (The high court order) “…would impinge on the future course of education of nearly 17 lakh students who are pursuing education in these institutions.”

- “…the finding of the High Court that the very establishment of the board would amount to breach of the principles of secularism appears to conflate the concept of madarsa education with the regulatory powers which have been entrusted to the board”.

- “…the Act does not per se provide for religious instruction in an educational institution maintained out of state funds”.

The top court had also pointed out that Article 28(1) of the Constitution provides that no religious instruction shall be provided in any educational institution wholly maintained out of state funds.

If the above are taken into consideration independently, it will be evident that the top court helped avoid a situation where the future of 1.7 million students would suddenly have been in jeopardy. Hence the Court realised that a summary yes/no decision on the issue would certainly go against the interest of the students. The High Court had ordered that the government must relocate all the 17 lakh students. Considering the condition of educational institutions (government funded and owned) in the country today, especially in the face of a huge deficit of teachers, the government would certainly have not been able to complete this relocation process any time soon. The top court acted cautiously and the stay was a well calculated decision.

Also, while the top court has asked the state to file its counter affidavit before May 31, it has given the appellants time till June 30 to respond to the state’s views. The final hearing has been fixed for the second week of July. That means the entire issue has been taken beyond the general elections, when the issue can be tackled with a saner mind.

As of now, the apex court has made it clear that “the object and purpose of the statutory board which is constituted under the Act is regulatory in nature”.

The Court said: “…if the object, and purpose of the PIL, was to ensure that secular education in core subjects such as mathematics, science, social studies and history, besides, the languages is provided in institutions imparting madarsa education, the remedy would not lie in striking down the provisions of the 2004 Act, but issuing suitable directions to ensure that all students who pursue their education in these institutions are not deprived of the quality of education that is made available by the state in other institutions.”

That certainly is a middle path, suggested by the top court.

“The state in our view does have a legitimate public interest in ensuring that students who pursue education in all institutions, whether primary, secondary or higher secondary level, receive education of a requisite quality and standard which makes them qualified enough to pursue a dignified existence upon receiving the degree which are awarded to them. Whether this purpose would require the jettisoning of the entire statute which has been enacted by the state legislature in 2004 would merit serious consideration,” the Court said.

Before declaring the Act “unconstitutional” and violative of the principles of secularism, the Allahabad High Court was hearing a petition that challenged the very constitutionality of the UP Madarsa Board and had also objected to the management of madarsas by the Minority Welfare Department and not the education department.

The appeal sad the Act violates the principles of secularism, which is the basic structure of the Constitution, fails to provide quality, compulsory education up to the age of 14 years/Class-VIII as is mandatorily under Article 21-A; and fails to provide universal and quality school education to all the children studying in madarsas. Thus, it violates the fundamental rights of the students of the madarsas.

The background

The Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act of 2004 was primarily enacted to streamline madarsa education in the country. The definition available was that they imparted education in Arabic, Urdu, Persian, Islamic studies, Tibb (traditional medicine), philosophy and other specified branches. Whether these are wholesome educational subjects remains a matter of debate, and whether a student of the subjects mentioned would be able to get a job with such knowledge in modern day India remains doubtful.

In Uttar Pradesh there are about 25,000 madarsas. Of these 16,500 are recognised by the Uttar Pradesh Madarsa Education Board. Of these 560 madarsas receive grants from the government. This leaves 8,500 more unrecognised madarsas.

What degrees are available here? The Madarsa Education Board grants undergraduate and postgraduate degrees under the names Kamil and Fazil, respectively. These are unlike any regular degree that is granted across the country and unlike any degree that would fetch a student a livelihood in India.

The diplomas under this board are known as Qari, while certificates or other academic distinctions are also granted by the Madarsa Education Board. The board conducts exams for the Munshi and Maulvi (Class X) and Alim (Class XII) courses.

The Madarsa Education Board is also mandated to prescribe courses, textbooks, reference books and other instructional material, if any, for Tahtania, Fauquania, Munshi, Maulavi, Alim, Kamil and Fazil.

The Supreme Court order comes within a definitive and narrow band. It said that the Allahabad High Court was “not prima facie correct” in believing that the madarsas will breach secularism.

To this end, the Supreme Court has walked a fine line and has been to the point.

Some sections of the Act

Before going any further, one needs to list some sections of the Act which came into force on September 3, 2004. Here are some portions of the Act (verbatim):

- “Madarsa-Education” means education in Arabic, Urdu, Persian, Islamic-studies, Tibb Logic, Philosophy and includes such other branches of learning as may be specified by the Board from time to time;

- The Board shall consist of the following members, namely (not all included):

(a) a renowned Muslim educationist in the field of traditional Madarsa-Education, nominated by the State Government who shall be the Chairperson of the Board;

(d) one Sunni-Muslim Legislator to be elected by both houses of the State Legislature;

(e) one Shia-Muslim Legislator to be elected by both houses of the State Legislature;

(g) two heads of institution established and administered by Sunni-Muslim nominated by the State Government;

(h) one head of institution established and administered by Shia-Muslim nominated by the State Government;

(i) two teachers of institutions established and administered by Sunni-Muslim nominated by the State Government;

(j) one teacher of an institution established and administered by Shia-Muslim nominated by the State Government;

(k) one Science or Tibb teacher of an institution nominated by the State Government.”

The Act also specifies Shia and Sunni members, failing to elucidate how such specific religious members will benefit students of an educational institution in achieving their lives’ goals.

The top court’s action has been commendable in that it has not upset the lives and careers of a large number of students and has opened the entire case to open debates. Whatever the post-election scenario, an open debate may be able to bring out more aspects of the issue. In the end, the Act can be suitably amended, instead of being junked altogether.