With a growing number of women alleging sexual assault by powerful politicians and even the governor of West Bengal, it raises the issue of identity secrecy granted to a rape victim as a protective mechanism enshrined in statute books to prevent any further trauma or indignity

By Sanjay Raman Sinha

Within a short span of few days, two incidents made headlines which underlined the legal flip side of sexual assault cases. The first case was a palace intrigue which allegedly took place in the Raj Bhavan in Kolkata. A woman contractual staffer accused West Bengal Governor CV Ananda Bose of molesting her; thereafter the Raj Bhavan showed CCTV footage of the premises to around 100 people. The women victim objected and said that the footage was released without her permission and that her identity was made public contravening the law and that the governor should be criminally charged for the act.

A few days earlier, the country was rocked by allegations of “mass rape” by JD(S) MP Prajwal Revanna. Women victims’ video was circulated in public and the hapless women were forced to abandon their homes in Karnataka’s Hassan district. This again was invasion of the rape victim’s privacy and breach of law.

There is a long-standing debate worldwide on the right to privacy of the rape/sexual assault victim and also on the freedom of press to report sensitively on the subject. The crime of rape is traditionally considered a crime of shame for women, and the resultant social stigma attached to the victim makes it imperative for non-disclosure of her identity. The victim is prone to suffer social ridicule and ostracization and this can mar her integration in the society. This acceptance flows from the fact that rape is more personal, traumatic and stigmatizing than other crimes.

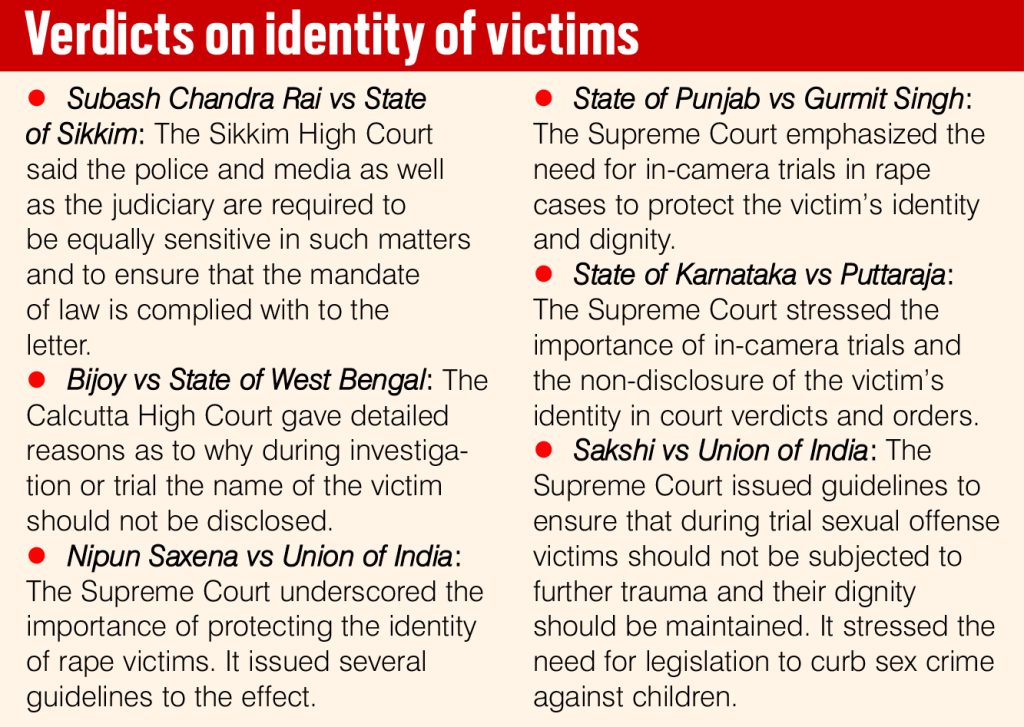

Disclosing the identity of a rape victim constitutes an offence under Section 228A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and is punishable with imprisonment up to two years and fine for those who reveal the identity of victims of sexual abuse in public. The law has been amended subsequently to add more sections of the IPC under its purview.

In April 2018, the Delhi High Court bench, comprising Acting Chief Justice Gita Mittal and Justice C Hari Shankar, strongly condemned the disclosure of identity of minor victim of Kathua rape and murder case. The bench stated: “Unfortunately the nature and manner of reporting of the alleged offence is being affected in absolute violation of specific prohibition of law disrespecting the privacy of victims which is required to be maintained in respect of the identity of a victim.” The top 12 media houses were issued notices in this regard.

In this context, it is noteworthy that to date, the Supreme Court of the United States has protected a news organization’s decision to disclose a rape victim’s name even though three states—Florida, South Carolina and Georgia—have statutes prohibiting the media from doing so. The activists there have termed it as a “conspiracy of silence”, which perpetuates gender stereotypes. The fact of the matter is that in traditional societies like India, “silence” in such matters is often the chosen option.

However, the Delhi gangrape case presented the other side of the picture when amidst national outrage, the victim’s parents chose to remain identified and Nirbhaya’s father said: “We want the world to know her real name. My daughter didn’t do anything wrong, she died while protecting herself. I am proud of her. Revealing her name will give courage to other women who have survived these attacks. They will find strength from my daughter.” But such instances of moral strength are few and far between. In most cases, the victim and the family embraces anonymity for reasons of social sanctity, denouncement and ridicule.

In Nipun Saxena vs Union Of India (2018), the Supreme Court bench, comprising Justice Madan B Lokur and Deepak Gupta stated: “Victim of a sexual offence, especially a victim of rape, is treated worse than the perpetrator of the crime. The victim is innocent. She has been subjected to forcible sexual abuse. However, for no fault of the victim, society instead of empathizing with the victim, starts treating her as an ‘untouchable’. A victim of rape is treated like a ‘pariah’ and ostracised from society. Many times, even her family refuses to accept her back into their fold. The harsh reality is that many times cases of rape do not even get reported because of the false notions of so called ‘honour’ which the family of the victim wants to uphold.”

In the same case, the bench issued a set of guidelines on the identity issue. The bench said the identity of adult victims of rape and children who are victims of sexual abuse should be protected so that they are not subjected to unnecessary ridicule, social ostracization and harassment.

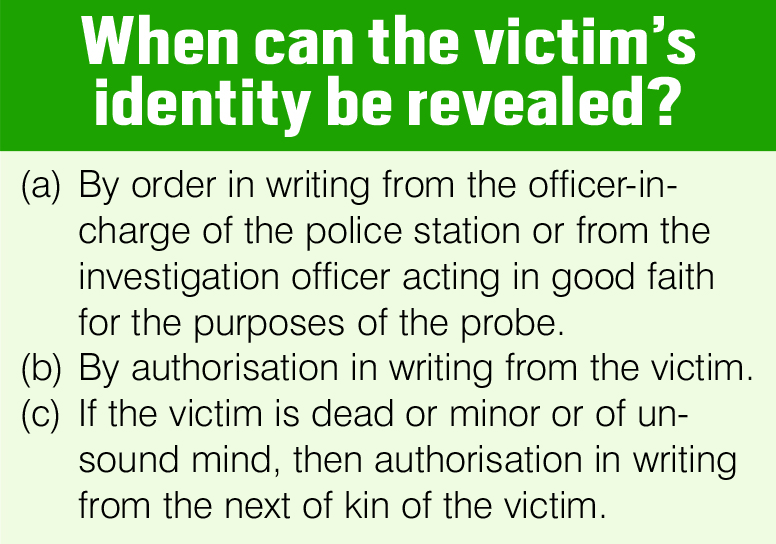

Though Section 228A IPC imposes a restriction on the name or identity of the victim being disclosed, if the accused is acquitted and the victim wants to file an appeal under Section 372 CrPC, she can move an application to the court, praying that she may be permitted to file a petition under a pseudonym. However, the name shouldn’t indirectly harm another person. When the victim is a minor, more care is taken. In fact, Subsection (2) of Section 23 of the POCSO Act states that no report in any media shall disclose identity of a child, including name, address, photograph, family details, school, neighbourhood or any other particulars which may lead to the disclosure of the identity of the child.

Based on the Supreme Court directions and related laws, the Ministry of Home Affairs sent a memo to all states and union territories to adhere to court guidelines in dealing with rape victims and their identity. Four points stand out:

(1) No person can print or publish in any media the name of the victim, or any facts which can lead to the victim being identified, and known to the public at large.

(2) The investigating officers are duty-bound to keep the identity of victims secret.

(3) The police officers should keep all documents in which the name of the victim is disclosed in a sealed cover.

(4) In case of a minor victim, disclosure of identity can only be permitted by the Special Court if such disclosure is in the interest of the child.

Further to the central government notification, it was expected that the norms would be strictly followed at the ground level. But the opposite is true. NGO Majlis, undertook a survey of 600 victims in a period of three years. The study revealed that in 36% cases, the victim’s name appeared in the judgment despite the Supreme Court guidelines to keep it confidential. In 154 cases, the chargesheet given to the lawyers of the accused had all the details of the victim.

Problems happen at the hands of politicians as well. In August 1, 2021, Rahul Gandhi had published a photograph with the parents of a minor girl who died under suspicious circumstances and her parents alleged that she was raped and killed. A case was filed against Gandhi at the Delhi High Court which disposed of a petition seeking registration of an FIR against him. Gandhi deleted the tweet which revealed the identity of the minor Dalit girl who was allegedly raped and murdered before being cremated in haste. He had published a photograph with the parents of the nine-year-old girl who died under suspicious circumstances on August 1, 2021, with her parents alleging that she was raped, murdered and cremated by a crematorium’s priest in southwest Delhi’s Old Nangal village.

Former Delhi Commission for Women chairperson Swati Maliwal also got embroiled in a controversy when she was booked for allegedly revealing the identity of the Dalit girl who was raped in Burari.

The laws relating to the protection of sexual assault victim’s identity are strong, the verdicts are comprehensive and the norms at the ground level are detailed. Yet, oftentimes, the victim’s identity is compromised. In most cases, it is by mistake; in some it may be deliberate.

It needs to be underlined that the “veil of secrecy” is not a “veil of shame”. It is a protective mechanism to protect the interests of the victim. There are provisions in law for wilful declaration of identity. These are for the few who by circumstance or courage of conviction opt for coming out of the shadows; for the most, the veil of secrecy is prevent further trauma and indignity.