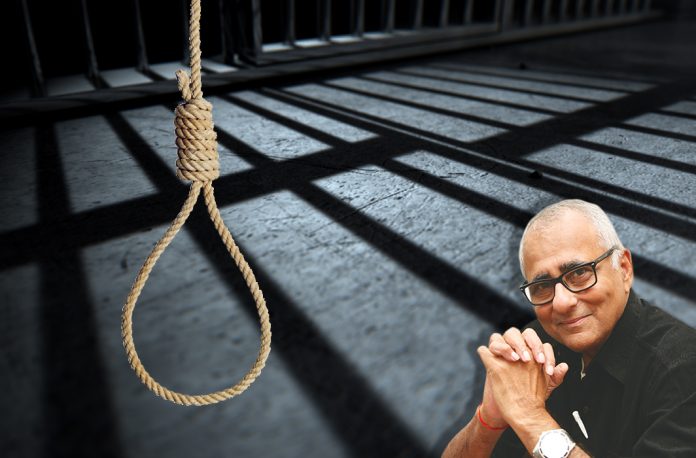

The judicial postponements, mercy petitions and reviews in the Supreme Court and High Courts, which have delayed the hanging of the convicted rapist-murderers of Nirbhaya, have once again ignited a national controversy over the ethics, efficacy and utility of capital punishment as a tool of deterrence. Even as 107 countries—including Russia—have done away with executions, the age-old debate about the death penalty—justice versus revenge versus deterrence—rages on.

In this context I recall a courtesy call I made in 2014 on then Chief Justice of India P Sathasivam who was due to retire in a week. Without referring to any specific case before him, the judge seemed highly agitated by judicial delays, particularly in the case of death row prisoners who suffer interminable mental torture or even go stark raving mad while awaiting decisions on mercy petitions. “This has to be remedied,” he said. Little did I know that a day later, a bench headed by him and comprising Justices RM Lodha, HL Dattu and SJ Mukhopadhaya would commute the death sentence of Devenderpal Singh Bhullar whose mercy petition had been pending for eight years following a 1993 Delhi bomb blast which killed nine people.

The judges cited Shatrughan Chauhan vs Union of India where “unexplained and inordinate delays” in deciding a mercy petition as well as mental and physical illness were found valid grounds for commutation of a death sentence to life imprisonment. Sathasivam’s last judgment as CJI once again catalysed the judicial and academic community to re-examine the whole death penalty issue. India Legal has tackled this subject in cover stories in the magazine as well as on its TV channel in which we featured guests, including academicians from the National Law University (NLU).

In 2017, an important social story that got lost in the political din of the Gujarat elections was a wide-ranging and thought-provoking report on capital punishment in India, titled “Matters of Judgment”. It is a landmark attitude study on the criminal justice system and the death penalty featuring 60 former judges of the Supreme Court of India. They include Justices AK Ganguly, Santosh Hegde, Ruma Pal, BN Srikrishna and RC Lahoti, who have adjudicated 208 death penalty cases among them between 1975 and 2016.

Dr GS Bajpai, registrar and professor of criminology and criminal justice, a frequent guest on India Legal TV shows, said at the seminar at which the report was released: “This report is not as simplistic as we think based on its face value and has to be decoded further with respect to the observations made by the judges. It is said that criminal law is deficient. I would say that it is not that criminal law is deficient but we have failed criminal law. It is the institutions that have failed criminal law in India. Fresh insights are not being imported into the criminal law of this country. It is as if we only like to debate. This study is not the conclusion but like a hypothesis which should be taken forward by law researchers.”

India Legal carried a comprehensive editorial on that report which probably has as much relevance in the context of today’s controversies as it did at the time when it first appeared. I reproduce below its major findings in the hope that it will create the atmosphere for a debate based on empirical data rather than pure emotion.

Of the 60 former judges interviewed, 47 had adjudicated death penalty cases and confirmed 92 death sentences in 63 cases. Considering that the death penalty represents the most severe punishment permitted in law, “we sought the views of former judges on critical aspects of the criminal justice system like torture, integrity of the evidence collection process, access to legal representation and wrongful convictions,” the study’s authors said in an introduction. The interviews also examined the meaning of the “rarest of rare” standard laid down by the apex court for awarding the extreme punishment in Bachan Singh vs State of Punjab, the appropriate role for aggravating and mitigating factors and the nature of judicial discretion during death penalty sentencing.

The final stage of the report examines the attitudes of former judges to abolition or retention of the death sentence “while exploring their thoughts on recent developments that seek to move away from the death penalty”.

This is not the first time this troubling legal subject of life vs death has been explored in India. In the Constituent Assembly of 1947-49, it was intensely debated, with Dr BR Ambedkar staunchly opposing the death penalty. In 2015, the Law Commission headed by Justice AP Shah proposed that the country should aim at complete abolition “but as a first step that it be done away with for all crimes except terrorism. Further, the Commission sincerely hopes that the movement towards absolute abolition will be swift and irreversible”.

Nonetheless, the NLU study is startling because it reveals an overpowering recognition and widespread anxiety among former Supreme Court judges about India’s criminal justice system because of extensive pervasiveness of torture, fabrication of evidence, the appalling inferiority of legal aid and unjust convictions.

For example, as Dr Anup Surendranath, director of the Centre on the Death Penalty, puts it: “Judges acknowledge the misuse of Section 27 of the Evidence Act as also planting of evidence. They acknowledged that torture was a reality. Only one of them said that it does not exist. Some said that it is expected that something like that will happen. They also acknowledged wrongful convictions. But wrongful convictions were eventually pitted against wrongful acquittals by some judges and were not viewed as independent problems.”

Here are excerpts of the key findings and recommendations of this exclusive survey:

There was explicit acknowledgment and widespread concern about the crisis in the criminal justice system due to the use of torture to generate evidence, fabrication through recovery evidence, a broken legal aid system and wrongful convictions. Though some former judges did offer justifications/explanations for this state of affairs, there was an overwhelming sense of concern about the integrity of the criminal justice system from multiple viewpoints.

However, the grave concerns about the criminal justice system did not sit quite well with the support for the death penalty. In conversations on the death penalty, the above mentioned realities of administering criminal justice in India hardly found mention. This disconnect was best demonstrated when 43 former judges acknowledged wrongful convictions as a worrying reality in India’s criminal justice system generally but when it came to the death penalty, only five judges acknowledged the “possibility of error” as a possible reason for abolition in India.

All former judges, irrespective of their position on the death penalty, were asked the reasons they saw for abolition or retention of the death penalty in India. In response, 29 former judges identified abolitionist justifications and 39 identified retentionist justifications. Fourteen retentionist judges took the position that there was no reason whatsoever to consider abolition in India and three abolitionist judges felt there was no reason to keep the death penalty.

Deterrence emerged as the strongest penological justification for retaining the death penalty, with 23 former judges seeing merit in that argument. However, most of them believed that the deterrent value of the death penalty flows from a general fear of punishment rather than any particular deterrent value specific to the death penalty.

The notion of a bifurcated trial, being a division between the guilt-determination phase and the sentencing phase, did not seem to hold much attraction for the former judges. Despite the sentencing process in death penalty cases having very specific requirements as per the judgment in Bachan Singh, the understanding of “rarest of rare” among former judges was determined/dominated by considerations of the brutality of the crime.

For a significant number of judges, the “rarest of the rare” was based on categories or description of offences alone and had little to do with the judicial test requiring that the alternative of life imprisonment be “unquestionably foreclosed”. This meant that for certain crimes, this widely-hailed formulation falls apart, rendering the sentencing exercise nugatory.

Despite the law setting out an indicative list of both aggravating and mitigating circumstances to be taken into account before determining the sentence, there was considerable confusion about the weight and scope of mitigating circumstances. Opinions varied considerably on whether factors such as poverty, young age and post-conviction mental illness and jail conduct could be considered mitigating circumstances at all, despite them being judicially recognised. A minority, in fact, did not believe in considering any mitigating circumstances at all while others believed that some categories of offences were simply beyond mitigation.

A striking feature, in stark contrast to the lack of confidence in the investigative process, was the confidence that judges had in discretionary powers in sentencing. This was despite the fact that more than half the judges believed that the background of a judge, including their religion and personal beliefs, were factors that influenced the choice between the death penalty and life imprisonment. There appeared to be no “bright line” which distinguished judicial sentencing discretion swiftly slipping into individual judge-centric decisions.

The law since Bachan Singh has evolved considerably on the issue of the scope of a sentence of life imprisonment. In December 2015, a Constitution bench of the Supreme Court affirmed that it had the power to impose a sentence for a fixed duration or for the natural life of the prisoner which was beyond the scope of remission. While 25 judges believed that this sentencing formulation was a legally valid punishment, seven found it violative of constitutional mandate and separation of powers.

CONCLUSION

“It is interesting that a significant number of retentionist judges identified abolitionist reasoning. It demonstrates the inescapable force of certain abolitionist arguments, but stark in its complete absence was any acknowledgment of the disparate impact of the death penalty on the poor and marginalised sections of Indian society. In a criminal justice system that is corrupt and violent at multiple levels, the burden on vulnerable sections of society is immense, and it is only accentuated within the death penalty context. As such, it is peculiar as to why this aspect of the death penalty in India did not find any real favour amongst former judges, especially those that were abolitionist.

“The disproportionate representation of the poor, illiterate, and socially marginalised within the death penalty context is abundantly clear in India and other retentionist countries across the globe. The contrast between the discussions on the criminal justice system and the confidence that seems to exist in administering the death penalty in the very same system is striking. The role of harsh punishments within a crisis-ridden criminal justice system is a complex one.

“The challenge really is to comprehend the considerations which drive the death penalty in a system that is plagued with torture, fabricated evidence, and wrongful convictions. As the harshest punishment in our legal system, the discussions and positions on the death penalty must feel the utmost impact of these worrying realities. It is the extreme ends of our criminal justice system, that need to be tempered by the grim reality that the former judges brought out so powerfully (in the first part of the report).

“Ultimately, the fact that their concerns about the criminal justice system has not migrated to their discussion on the death penalty is indicative of the terms on which multiple competing interests get balanced.”