Justice Karanam Sreedhar Rao has rightly focused attention in his column in this issue of India Legal on the malignancy that has metastasized throughout our judicial system. It is an affliction known as pendency, a fancy word for interminable delays in the delivery of justice in both civil and criminal cases. Supreme Court Chief Justice Dipak Misra recently attributed this to what he called the “adjournment disease”. He was referring to a major flaw in the system which allows lawyers and judges and litigants to play fast and loose with it by escaping hearing dates when convenient, or using procrastinating tactics to defer ongoing cases to future dates.

One painful example is of a company petition in the Karnataka High Court that is awaiting admission since 1985! Rao notes: In the Calcutta High Court, a civil suit is pending since 173 years. It was filed prior to the establishment of the Calcutta High Court 144 years ago. There are nearly 2.96 crore cases pending in subordinate courts and 5,000 judges are needed to tackle the pendency. In the High Courts, 31,16,492 civil cases are pending, out of which 5,98,631 go back over a decade; and 10,37,465 criminal cases are pending of which 1,87,999 have crossed the 10-year mark.

Statistics are easy to gloss over, just so many numbers. But if you give a human face to every one of these numbers, you will see that this situation is not only tragic but also a damning indictment of the working of our constitutional government. The fundamental principle of the Rule of Law is to ensure speedy justice to all who need it. But the system seems unable or simply refuses to deliver it.

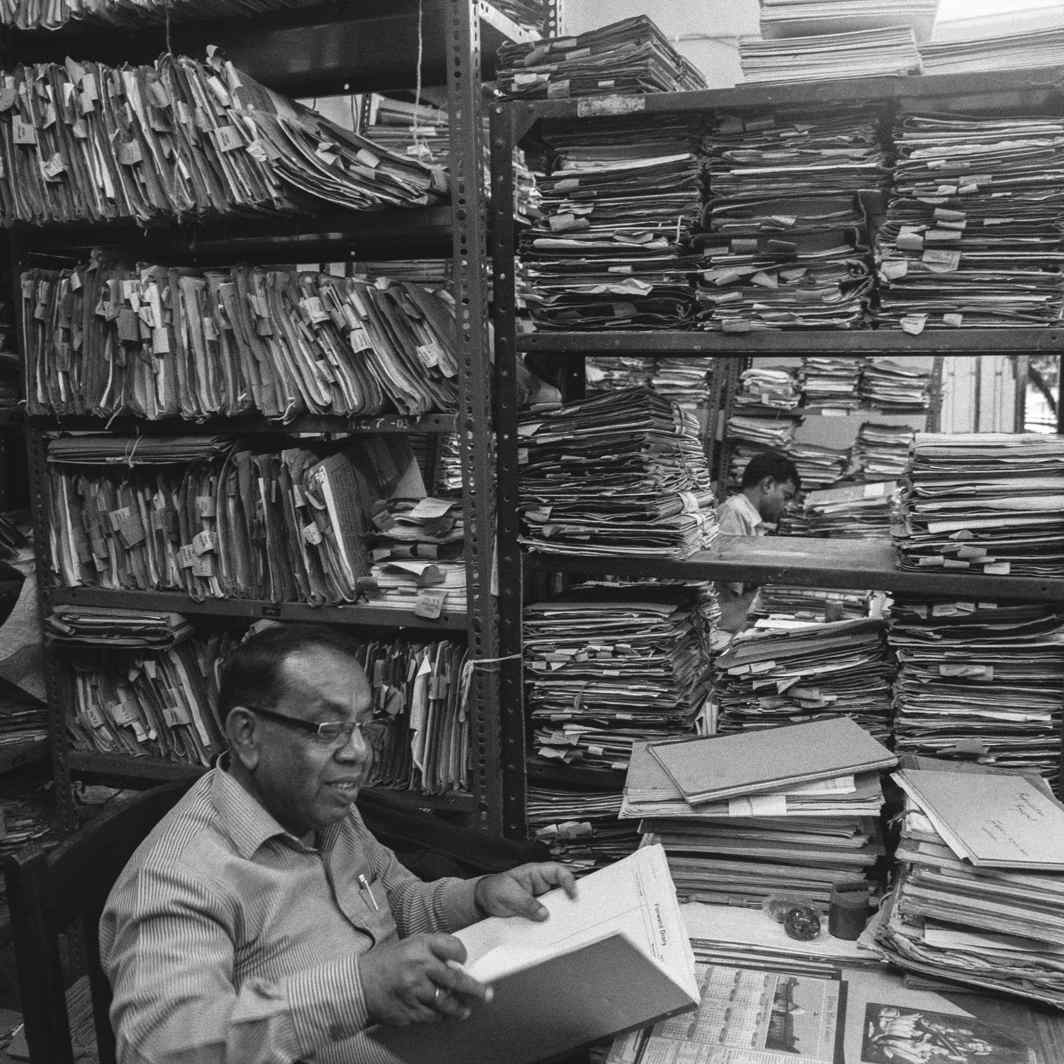

Astonishingly, the malady has not been impervious to diagnosis and remedial prescriptions from government and the judges themselves. But the sickness refuses to go away. Analyses and recommendations are simply stuffed into bureaucratic drawers and forgotten. Law commissions have come and gone, judgments have been penned and delivered, but the harrowing, soul-destroying delays go on forever.

The adjournment disease, an important contributor to the larger affliction, is not the only ailment that plagues the system. The Law Commission of India in its 77th report submitted about 40 years ago mentioned frequent adjournments as an important cause of delay. Though the Code of Civil Procedure provides that “no such adjournment shall be granted more than three times to a party during hearing of the suit”, Indian courts appear to pay scant heed.

Most people will be startled to learn that this scourge was present even in pre-Independence British India. Some of the high-level groups which investigated the causes include the Rankin Committee (1924); a High Court Arrears Committee under the chairmanship of Justice SR Das (1949) and a committee under Chief Justice Hidayatulla (1969). The work of this last committee was extended and later chaired by Justice Shah in 1972. It was known as the High Court Arrears Committee.

The collective findings of various commissions and committees are well summarised by the International Journal of Legal Developments and Allied Issues (Volume 2 Issue 6). The major factors as spelled out in this illuminating study are:

- Vacancies in Judiciary. From the Supreme Court downwards, the entire system is riddled with this deficiency. Part of it has been caused by the Executive-versus-Judiciary tussle over the Collegium-National Judicial Appointments Committee (NJAC) imbroglio. The stalemate was best summed up by former Chief Justice TS Thakur: “Vacancies in the judiciary, especially state High Courts, have become a national challenge, and efforts were being made to persuade the government to expedite the matter. We have been talking very often about pendency of cases in the courts.”

- Inadequate number of courts. The Law Commission of India in Report No 245 deals with the establishment of additional courts in elimination of delay and speedy clearance of matters. In fact, Imtiyaz Ahmad v State of UP specifically gave directions for creation of additional courts.

- Judicial officers unable to tackle cases involving specialised knowledge. Lack of specialised knowledge on the part of judges directly impacts the justice delivery system. With the advancement of science and technology, many new offences such as cyber pornography and cyber stalking have emerged.

- Abuse of Public Interest Litigation. Under the guise of PILs, petitioners often seek to promote private or political vested interests, causing consequent delays. For this reason, Justice Bhagwati cautioned against misuse of PILs in the landmark judgment Janata Dal v HS Chowdhari.

- Lack of adequate arrangements to monitor, track and bunch cases for hearing. This inadequacy leads to an incalculable waste of time. Added to this is the frequent transfer of judges which retards the justice delivery system. Often, with no continuity available following a transfer or a bench-change, a new judge orders a de novo trial in which the wheel has to be re-invented at the cost of an enormous delay.

- Role of administrative staff of the court. If court babus underperform or are derelict in their duty, they contribute to hampering a speedy trial. In addition, a large number of appeals also impede speedy disposal of cases because the courts are busy in disposal of the appeals backlog.

- Delay in serving of summons. People are naturally inclined to avoid summons. Add to this the lack of qualifications or knowledge of process servers, their negligence and lethargy. Very often, they fail to serve the summons in time, and are virtually free of proper supervision.

- Delay in filing written statement. The law provides that “defendant should file written statement within 30 days from the date of service of summons on him”. But this provision is not followed in true letter and spirit. Defendants tend to prolong the matter.

- Non-appearance of parties on the day fixed for hearing. The provisions of CPC state that if both parties don’t appear on the day fixed for hearing, the suit can be dismissed. Consequently, a plaintiff may file a fresh suit or the court may restore it.

- Non-compliance by judges of laid-out procedures. Trial judges often do not read in advance the pleadings of the parties. This leads to inordinate delays in framing the issues and proceedings in a proper and timely manner.

- Delay in investigation. In criminal cases, the role of the police is significant in the speedy disposal of cases. If a police officer completes his investigation in time, it will speed up the justice delivery process. This rarely happens. And delays in filing the charge sheet or the completion report hamper speedy trials.

- Excessive Cross-examination. The Law Commission’s 77th report states that “sometimes questions are put to the witnesses in cross-examination which are unnecessary, slanderous and harassing. It is on such occasions it becomes necessary for the trial judge to control the proceedings”. The Indian Evidence Act also prohibits asking indecent and scandalous questions. The courts are also directed to forbid questions which intend to annoy or insult. Further, the Code provides that questions should not to be asked without reasonable grounds. Such unnecessary questioning wastes the time of the court. The role of a judge is extremely pertinent in supervising cross-examination.

- Practice of taking on a large case load. Scheduling too many cases on a day is not desirable if there is no reasonable chance of their being taken up for hearing. The Law Commission observed: “In the matter of controlling the case diary and in fixing cases for each working day the trial judges discharge a very important duty. There is a tendency on the part of presiding judges to leave the matter of fixing dates to their readers and sheristadars (subordinate officers).”

In 2008, Common Cause, an NGO founded by HD Shourie, filed a writ petition before the Supreme Court in which it sought redressal for crores of Indian citizens “who are routinely denied justice because of its delayed and therefore, ineffective dispensation. It is to restore to them their fundamental and constitutional rights guaranteed under Articles 21, 14, 19 and the Preamble, and to enforce the constitutional obligations of State under Article 39A of the Constitution of India…. As a consequence of this, the petitioners fear that there has been a loss of public confidence in the judiciary, and an increasing resort to lawlessness and violent crime to settle disputes.”

The petitioners stated that their motive in going to the apex court was to ensure that “public confidence in the judiciary (is) restored immediately, in order to arrest and reverse this negative trend”. The petitioners reiterated that over the past half century, various authorities such as the Law Commission, benches of the Supreme Court, eminent lawyers and judges, had identified problems in the judicial system, reasons for delay in the dispensation of justice and specific measures to overcome delays and expedite the disposal of cases.

The petitioners reminded the Court that the Supreme Court had recognised these problems and taken several initiatives such as passing directions in All India Judges Association (2002) 4 SCC 247 to increase judge-strength five-fold, to fill up existing vacancies by 2003, to create ad hoc posts and commensurate infrastructure by 2007, and yet these directions still awaited implementation.

The Court had also passed directions in Salem Advocate Bar Association, Tamil Nadu Vs Union of India (UOI), (2005) 6 SCC 344, P Ramachandra Rao (2002) 4 SCC 578, Shambhu Nath (2001) 4 SCC 667, and Hussainara Khatoon, 1980 1 SCC 93, to strictly adhere to procedural laws laid down in the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC) and the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) respectively, in order to ensure effective and timely disposal of both civil and criminal matters. “Yet many of these directions are not taken seriously, with the result that justice is delayed and denied to litigants. The Parliament has also, enacted several laws including amendments in the CPC 2002, and the CrPC through new or revised sections to streamline and rationalize procedures. The aim today, is to merely achieve strict implementation of directions and laws already laid down. Today therefore, the petitioners merely seek implementation of past directions by this Court and of laws that have already been enacted by Parliaments

“Many cases in India take up to 10 years for disposal and usually take far longer than the stipulated 6 months or 2 years for trials, resulting in enormous pendency. The pendency of cases in India, was about 3 crores in 2007. Although justice is meant to be ‘simple, speedy, cheap, effective and substantial’, yet it remains elusive to Indians, and one of the major reasons are these delays in the dispensation of justice.”

This was stated by the petitioners a decade ago. The figures have not changed much since then. The effective implementation of many such recommendations is still pending, proving the adage that in India the more things change, the more they remain the same.

—Inderjit Badhwar is Editor-in-Chief, India Legal.

He can be reachededitor@indialegallive.com