~By Inderjit Badhwar

In a democracy, starting with the People, we all have our crosses to bear. And bear them we must, with fortitude and unadulterated responsibility. Let’s start with my profession. And the area—law—which this magazine focuses on. Reporters must do their job. So must the judicial system perform its onerous duties. The reporter’s task is to slog, to dig, to seek and write the truth objectively and fairly. The judge’s task is to examine what is presented or argued before him in the context of established jurisprudence and evidence-based testimony and depositions.

Often judges and reporters are at loggerheads. They blame one another for overstepping bounds. But eventually, both must withstand the withering scrutiny of time. Both must live with their conscience. The law is based, ultimately, on conscience. It is the product of the evolution of the human spirit. Stalin’s mock trials were decisively exposed for what they were, as were the social depredations of Mao’s Cultural Revolution even when, at the time these cruelties occurred, there was no press (except for government-oiled fake news propaganda organs) to report them.

The law can, and often must, doubt the news as it goes about its business of delivering judgments. But then, so should journalists doubt judgments even while being careful of avoiding contempt in societies which give constitutional legitimacy to free speech. Under India’s Constitution, judgments prevail over newspaper reporting. But judgments can also be reversed by tenacious, journalistic fact-finding.

Ergo, the one argument I find harrowing and narrowly self-serving is that newspaper reporting and investigative fact-finding and questioning of malafide official decisions by the authorities should be given no credence by the legal or administrative systems of justice “because they are only newspaper reports”. Or: “Oh, but that which is now sought to being exposed happened several years ago, so why is this being brought up now.” This is arrant nonsense that flies in the face of the worthy doctrine of telling the truth not only to power but also of unmasking the terror with which power suppresses the truth.

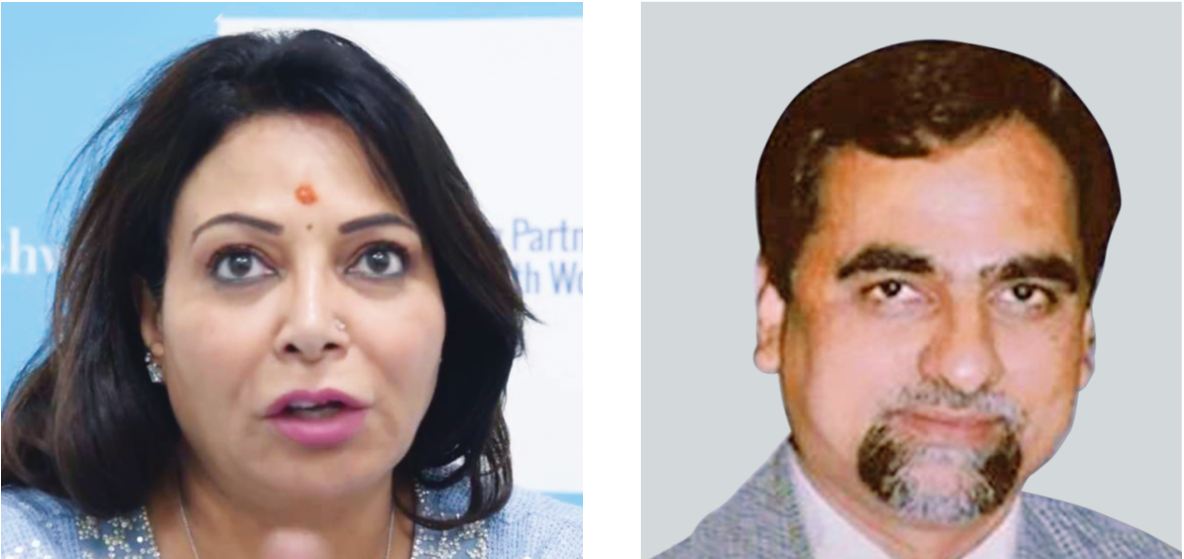

This was an argument often cited by the lawyers opposing the petitioners who wanted the Supreme Court to order a new inquiry into the untimely death by “cardiac arrest” of Special CBI Judge Brijgopal Harkishan Loya in 2014. Caravan magazine published 22 stories based on two years of investigations, most of them taped. In 2017, the magazine interviewed family members of the judge alleging foul play in his death. On April 19, 2018, the Supreme Court dismissed all petitions seeking an independent probe.

The Court, based on its own predilections, did what it had to. The reporters for Caravan and other independent journals, too, must continue to do what they have to. Without casting aspersions on the Court, the reporters are on record saying they stand by every word of their stories. The red herring that was constantly thrown in the middle of the Supreme Court hearings was that the Caravan story had appeared nearly three years later and should be discarded as a credible source. It was, some argued, “mischievously” motivated.

Which brings me to the central point of this article. I am not arguing that in this era of virulent fake news, magazine stories should be taken as gospel. But if there is sufficient smoke, and the journal has a reputation for credibility, the fire must be investigated. Dismissing a source of information because it is a “newspaper story”, or is “old”, is a specious argument. Perhaps the most powerful newspaper story which won the iconic Seymour Hersh the Pulitzer prize—the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam war—appeared after the atrocity in which hundreds of innocent men, children and women were raped, butchered and burnt alive by American soldiers in 1968, appeared over a year later. That is the time it took Hersh to investigate the story which had been reported in a fake news release by the American army as a fierce armed encounter between Vietnamese resistance rebels (Viet Cong) and the Americans.

The leader of this killer squad exposed by Hersh was ultimately tried and jailed along with others for their role in perpetrating this war crime by the American justice system. It took Hersh over a year of foot-slogging research to piece together the article. It takes time to uncover what somebody, especially the government, is trying to cover up. I am sure that defenders of the crime tried to dismiss this as a conspiracy story and “old” news, but the persistence of the American media ultimately prevailed and the judge and the reporter worked in tandem to defend the liberties enshrined in the American Constitution.

The worldwide “Me Too” movement, aimed at abolishing the culture of impunity in harassing and raping women, has allowed women, who have been subjected to sexual abuse by the male power structure, to come out in the open and tell their stories and even take celebrities to court decades after the alleged crimes were committed. And many of these women, as in the case of President Donald Trump, comedian Bill Cosby and director Harvey Weinstein, have given their accounts to newspapers. They are not socially or legally ignored because they are “newspaper stories” or because the incident occurred several years earlier.

“The political media exposé, of the sort that invariably earns the suffix ‘-gate’ in the United States, can come in a surprising variety of shapes and sizes”, an international columnist recently said. “The coverage of Watergate, sustained in The Washington Post over more than 300 stories, sank a presidency. In 1987, India’s own Watergate broke in The Hindu, which printed hundreds of documents to expose the Bofors corruption scandal, involving kickbacks received by politicians in exchange for a defense contract. On the other hand, independent India’s first momentous political scam broke in 1957 with what seems, in comparison, to be a pebble hurled at the side of an ocean liner—and yet it forced the swift resignation of a finance minister, TT Krishnamachari.”

On September 4, 1957, Ram Subhag Singh, a Congress politician and Member of Parliament, rose to ask a question in Parliament: “Will the minister of finance be pleased to refer to a report in The Statesman (Delhi edition) of Aug. 3, 1957, to the effect that a sum of one crore [10 million] rupees from the funds of the Life Insurance Corporation had been invested in a private enterprise with its headquarters in Kanpur and state:

(a) the name of the private enterprise…

(b) the total amount invested so far; and

(c) the reasons for investing the funds in a private enterprise?”

This newspaper report ultimately unearthed what was known as the “Mundhra Scandal”. As a blogpost in The New York Times put it: “The crusade to demand an explanation…was led, in an odd soap-operatic twist, by Feroze Gandhi, son-in-law to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. In hectoring speeches in the Lok Sabha, Mr. Gandhi charged that the principal finance secretary, H.M. Patel, and the finance minister, Mr. Krishnamachari, had pushed LIC’s investment through. (The socialist leader Madhu Dandavate, in his memoir Dialogue with Life, recalled a Congress Party member’s weak riposte to Mr. Gandhi: ‘You are basing your allegations just on newspaper reports. This is not proper. Do you have evidence?’ In our age, when allegations are made on the basis of little else but media reports, this remark must sound sweetly naïve.)”

Again, closer to home, it would be worth reminding all Indians that the country has not been immune to being rocked by investigative journalism, no matter what the fate of the Loya inquiry: Journalist Sanchari Pal has compiled a short ready reckoner (even though I can quote several more examples) whose excerpts I reproduce below. She says, (notwithstanding India’s rapid fall in the worldwide index of press freedoms during the last few years) that all these examples serve as inspiring reminders of why diligent investigative journalism is immensely valuable—in what it can do for ordinary folks, for society and the field of professional journalism. Excerpts from Pal’s summation:

The Hindu’s Bofors Expose. The scandal that broke in 1987 (on Swedish radio!) marked a watershed for India—it was the first time corruption became an intensely public and political issue. The scandal was uncovered mostly by the Chennai-headquartered The Hindu and reported by Chitra Subramaniam-Duella and N Ram. Almost 200 documents relating to Bofors were secretly sourced, verified and translated from the Swedish language before being published along with interviews and analytical pieces.{The case is still under some kind of investigation}

Such was the public fury stoked by this investigation that the government in power eventually ended up on the losing side in the 1989 general election.

Tehelka’s Defence Deals Expose. Even as the nation was trying to find its feet after being knocked off balance by the massive Bhuj earthquake, on March 13, 2001, Tehelka published an investigative report that ripped the lid off the murky world of defence deals.

Carried out using hidden cameras, the investigation (called Operation West End) publicised secret videotapes of top politicians, bureaucrats and military officials accepting bribes from two reporters (who posed as arms agents). The resulting furore created a major political storm and led to the resignation of those indicted by the videotapes. Interestingly, the same year, Tehelka also blew the lid of the explosive match-fixing scandal in Indian cricket.

Indian Express’ Cement Scam Expose. On the morning of August 31, 1981, readers of the Indian Express woke up to find a meticulously-researched expose on corruption in the grant of government cement quotas, complemented by supporting evidence and a blistering analysis that ran into 7,500 words. The swift, bold and bloodless journalistic coup has since come to be known as India’s Watergate—or the Cement scandal.

Almost overnight Arun Shourie, the then-executive editor of the Indian Express, became a national “hero” for his consciously studied and fearlessly pursued investigation of organized corruption in high places. In fact, it was after this incident that the irrepressibly buoyant MP Piloo Mody famously remar-ked, “Can you imagine the improved state of the nation if we had 10 Arun Shouries working instead of one?”

Indian Express’s Human Trafficking Expose. The name Ashwini Sarin is not very famous, but in the world of media, he is known as the man who showed how investigative journalism can further the cause of democracy. His sharp and penetrating investigative articles exposed the family planning atrocities during the Emergency, the multi-crore defence vehicle disposal racket and the torture of Tihar Jail inmates.

However, the Indian Express reporter is best known for his incisive report on human trafficking that created a whole discourse around flesh trade, controversial as it may have been. In 1981, he exposed the sordid racket by breaking the law himself (when he bought a tribal girl named Kamala) and showed how easy it was to buy humans in India. His work also inspired the movie and play named Kamala.

Open Magazine’s Nira Radia Tapes. In November 2010, Open magazine carried the transcripts of telephone conversations between Nira Radia (a political lobbyist cum PR honcho) and politicians, industrialists, officers of corporate houses and senior journalists. The tapes—wire-tapped by the Income Tax department on a tip-off by the Central Board of Direct Taxes—shone a harsh light on the murky manipulations that take place at the highest levels in the country to manoeuvre government formation, influence public opinion, and cater to corporate interests.

One of the fallouts of this story, she says, is that the indicted corporates group terminated all commercial engagement with the Outlook Group but the magazine’s undaunted editor (Vinod Mehta) stood his ground.

I’d like to end this with two favourite quotes: “The truth is what someone is trying to hide. The rest is advertising.” And (from the great Thomas Jefferson): “If I had to choose between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

P.S: Thanks, Sanchira, for this guidance. It helped me a great deal in focussing this piece which has long been on my mind.