Has the Supreme Court’s firecracker sale ban given the government a rare chance to remedy the crisis of air pollution or is it an example of judicial overreach and moral policing?

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

It is a decision that has taken the citizens of the national capital region by surprise and evoked strong and varied reactions. The Supreme Court’s reinstatement of a ban on sale of firecrackers during Diwali celebrations in the National Capital Region (NCR), more specifically until November 1, has been both welcomed and slammed. It has comforted some, angered others and, inevitably, taken a political and religious slant. Members of the right-wing were quick to slam the ban as being “irreligious” and complained of being singled out as Hindus to bear the burden of reform, though their claim is purely reactionary and not based on fact. Tripura governor Tathagata Roy promptly tweeted: “First, they targeted the ‘Dahi handi‘ custom, now its fireworks, perhaps tomorrow the ‘award wapsi gang’ will use environmental pollution as an excuse to call for an end to Hindus cremating their dead.” Roy was a member of the BJP National Executive before his appointment.

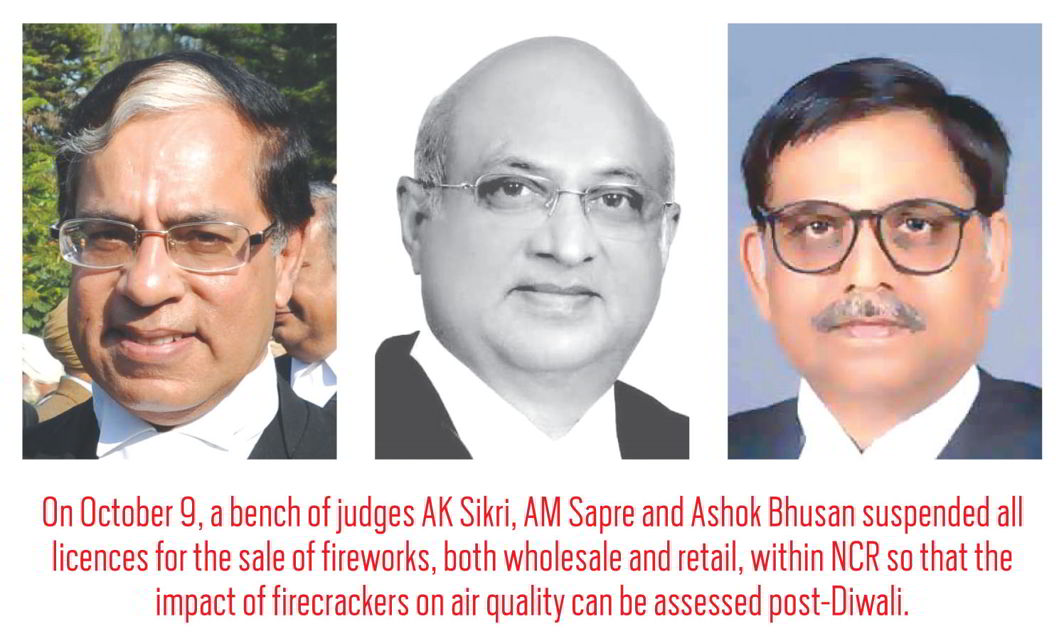

On October 9, a bench of judges AK Sikri, AM Sapre and Ashok Bhusan put in abeyance an earlier September 12 ruling by a different bench of the same court, relaxing a November 11, 2016, order suspending all licences for the sale of fireworks, both wholesale and retail, within the NCR. The Court had been ruling on a petition moved in 2015 by three infants—Arjun Gopal and Aarav Bhandari, aged six months each, and Zoya Rao Bhasin, all of 14 months old—represented by their lawyer fathers. This meant that the petitioners had not, as is being assumed, acted of their own accord. Their plea was based entirely on the issue of pollution, and the sharp rise in harmful particulates that is evident during Diwali, primarily because of the bursting of firecrackers. “We are of the view that the order suspending the licences should be given one chance to test itself in order to find out as to whether there would be a positive effect of this suspension, particularly during Diwali period… Further orders in this behalf [sic] can be passed on assessing the situation that would emerge after this Diwali season,” the bench, headed by Justice Sikri, said.

The September 12 order of the Court, passed by a bench of Justices Madan B Lokur and Deepak Gupta, had ruled out a blanket ban, capping the number of firework sale licences in the capital at 500, demarcating silence zones and outlawing the use of antimony, lithium, mercury, arsenic and lead in the manufacture of fireworks, while permitting the sale of fireworks containing aluminium, sulphur, potassium and barium, in its detailed 16-point guideline. This order is being seen as saner and more moderate by many from among civil society. Some commentators, such as senior journalist Karan Thapar, have also questioned the NCR-only nature of the ban, publicly conjecturing that it might be because the Court sits in Delhi and hence “worries about the pollution around it. For now, Mumbai, Bangalore, Chennai, Kolkata, Hyderabad, are not of equal concern”.

The smoke from crackers gets trapped in the lowest layers of air owing to the autumn smog with deleterious effects on the health of children, the elderly, asthma and pulmonary disease patients.

The case for regulating, indeed reducing, use of fireworks is unquestionable, no matter what dark conspiracy the right-wingers are seeing. Over the last 10 years, Delhi’s population has seen a quantum jump and is now unofficially at 24 million. If this trend continues, says ecologist and National Green Tribunal member CR Babu, by 2030 it will become the most populous city in the world. The population rise has increased the corresponding pressure on resources, says Babu, justifying the NCR focus of the order. That means pollution levels have risen correspondingly, more so in autumn and winter. The smoke from crackers gets trapped in the lowest layers of air owing to the autumn smog, with deleterious effects on the health of children, the elderly, asthma and pulmonary disease patients. As Babu told India Legal: “Last year, it took a week for the plume of smoke over the city after Diwali to disperse. So, anything you add to the atmosphere will be at the cost of public health.”

A January 2016, 334-page study on air pollution and greenhouse gases in Delhi prepared by IIT Kanpur shows how PM10, PM2.5 and sulphur dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere shoot up in winter. It also lists the causes of pollution—industrial emissions, construction work, transport and biomass or stubble burning by farmers. There is no mention of fireworks, though it is one of the usual suspects, albeit a minor one, as argued by ban critics, as, after all, compared to all other forms of pollution, Diwali happens only for a short time, and once a year. Pertinently, though, have the courts shown equal will in taking on the main culprits? Or has it shied away now and again, seeing as it involves ruffling the feathers of powerful oil, gas and automobile lobbies?

The ban has actually hit the domestic fireworks-making industry hard, especially units like Standard Fireworks in Tamil Nadu’s Sivakasi, India’s firecracker hub, which has been reporting a 20 percent loss year-on-year for the last five years in the face of competition from Chinese manufacturers. It is also likely to choke the livelihoods of lakhs of workers there. “Diwali is the time we make maximum profits and the SC order will smash many units,” Asai Thmabi, president of the Tamil Nadu Fireworks and Amorces Manufacturers Association, says. His concern is echoed by thousands of shopkeepers and traders in Delhi, many of whom are small roadside vendors, who wait all year to do business and now risk impoverishment, even penury. On October 13, the SC rejected their application, refusing to modify its order. However, while admitting that the Court should have taken this step much ahead of the festival, Babu advises them to find alternative sources of income and suggests the government help in their rehabilitation.

But what about the indigenous knowhow involved in the making of the crackers, generations of tradition and the cultural and recreational aspects of the festival? Not very long ago, Diwali was for farmers and others a method of pest control. Will all of that now be history? Babu rightly says that one must “balance their activities so that these are environmentally sustainable”.

But what was the Court doing all this time? Why did it not arrange for alternative remedies in advance, perhaps, a stricter timeframe for burning of crackers, communal fireworks displays rather than at individual homes, or even, as Thapar suggests, have the ailing and unwilling “leave the city for 48 hours and add the cost as an additional tax on firecrackers”?

It brings up the topic of moral policing and its predominance in our society, not only by the Hindutva brigade or misogynists or women who have learned to be fearful, but by the common man who has internalised these practices and engages in being a killjoy just to show off his social awareness and throw his weight around but with his vanity intact and without the smallest sacrifice. Why else would he oppose the odd-even rule, not use CNG or public transport and continue to add vehicles to his household? As the Court is a microcosm of society, there is no reason why this mindset should not have pervaded its premises. Perhaps this is why senior journalist Shekhar Gupta has found the order “troubling” and criticised the invoking of Article 142 of the bench, saying it is “for exceptional use and not the norm”. Others have accused the Court of outcome-based judicial overreach and compared the prohibition with its earlier national anthem order.

There is also the matter of disposing of the 50 lakh kg of fireworks which has already arrived in the capital before the ban. With a multiplicity of agencies in charge of enforcing it and our talent for jugaad, there is every chance that some of it might actually end up reaching the buyers. This will defeat the order, but if it succeeds, it will give the authorities a chance to measure Diwali in terms of air quality and come up with a logical, well-thought-out plan next year on what needs to be done to give citizens better quality of air to breathe. This year, thankfully, not everyone will be going crackers.