The recent apex court ruling that children in the age group 10-14 years should not be expected to commute long distances to schools is a pertinent one. But it remains to be seen if it can be applied across the country

~By Naveen Nair in Thiruvananthapuram

In what educationists in Kerala see as a judgment that brings relief to children, the Supreme Court has ruled that kids in the age group 10-14 years cannot be expected to walk long distances to attend school. The apex court’s September 8 decision came after it heard an appeal filed by the Palathingal MLP School in Parappanangadi, North Kerala, against a high court order setting aside a notification issued by the state government which had upgraded the school from lower primary to an upper primary one.

The government had elevated the Palathingal MLP School to the upper primary level because children who pass out from the fourth standard there had to walk long distances or commute by bus to the nearest upper primary school in the area.

The state government order was challenged by the manager of a rival school on the grounds that Rule 2 of Chapter V prescribed under the Kerala Education Rules (KER) 1959 were violated to facilitate the upgradation and that no notices were issued to other schools in the vicinity seeking objections if any. Both the single and division bench of the Kerala High Court set aside the order of the state government which prompted the MLP School to approach the apex court.

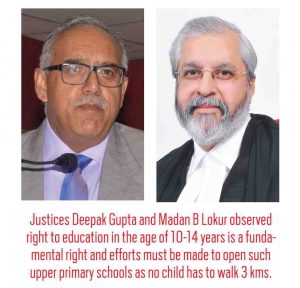

The Supreme Court set aside the high court judgment and viewed the case as one which also impinges on the fundamental right of children to education. The divisional bench of the apex court comprising Justice Madan B Lokur and Justice Deepak Gupta reinstated the Kerala government’s permission so that the school can now maintain its upper primary status.

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT

The apex court bench made this pertinent observation while delivering its judgment: “We cannot expect children in the age group of 10 to 14 years to walk 3 km or more to attend school. The right of education up to the age of 14 is now a fundamental right under Article 21A of the Constitution of India and if this right is to be meaningful then efforts must be made to open upper primary schools in such a manner that no child has to walk 3 kilometers or more to attend School.’’

While setting aside the high court judgment, the apex court also cited Rule 3 of the KER which allows flexibility to the state government to waive rules in exceptional circumstances. It states: “Where the Government is satisfied that the operation of any rule under these Rules causes undue hardship in any particular case, the Government may dispense with or relax the requirements of that rule to such extent and subject to such conditions as they may consider necessary for dealing with the case in a just and equitable manner.”

While setting aside the high court judgment, the apex court also cited Rule 3 of the KER which allows flexibility to the state government to waive rules in exceptional circumstances. It states: “Where the Government is satisfied that the operation of any rule under these Rules causes undue hardship in any particular case, the Government may dispense with or relax the requirements of that rule to such extent and subject to such conditions as they may consider necessary for dealing with the case in a just and equitable manner.”

Advocate Huzefa Aziz Ahmadi, who appeared on behalf of the MLP school, says that though the Supreme Court’s main objective was to point out a crucial legal aspect that was missed out when the HC set aside the government order, the final judgment would have far reaching implications in the primary education sector in not just Kerala but across the country.

Ahmadi told India Legal: “What the SC has said is that the high court had missed one vital aspect that when the notification on education rules was issued it also included the power of relaxation to the compliance of the rules which was to be taken into account if any rule caused extreme hardship to children. If such hardship exists the state government exercises the power to do away with the provision. This was overlooked by the lower court while passing the judgment.”

Undoubtedly the judgment comes across as a landmark one which lawyers like Ahmadi say would set a precedent for such cases in the future. Notes a lawyer: “By comparing the hardship faced by a child in seeking education as a violation of a fundamental right as enshrined in the Constitution, the apex court has perhaps taken the argument to a different level from where it could perhaps slowly become an obligation on governments to follow the directions of starting upper primary schools at not more than three kilometers vicinity of population.”

NATIONAL IMPACT

But the big question that still remains is whether the judgment can be applied across the country. Shajar Khan is a well known educationist in Kerala who has led many a fight to make the system better. Even he has his doubts about its nationwide impact.

He told India Legal: “In Kerala this will no doubt work and there is very less chance of this being challenged because not only the state has a very high density of population which makes it obligatory of the government to start more schools but the terrain is also not a difficult one compared to the rest of India. But I doubt whether this would work in, say, hilly areas in north India and other parts of the country where the population is so scattered and terrain hostile. Perhaps we need to be more practical in terms of the needs of each place.’’

Valsaya Menon, a teacher at a primary school in Kottayam says the decision is a much needed wake up call for the education sector. She said: “I think we live in an age where everyone should be encouraged to at least complete their primary education. For that to happen you need to ensure that the poorest and the most marginalized children also get a chance. In that context it is always an obligation for the state to bring the school as close to where the children live which will encourage them not to keep away from it.”

In the case of Parappanangadi School, the Supreme Court would surely have taken into account the social factor. That the school is located in a poor locality dominated by the Muslim minority community does find mention in the judgment.

Perhaps, the apex court’s observations can be used as a benchmark and followed in spirit when state governments plan and set up schools.