This controversial rule of some schools could well go against the Juvenile Justice Act and invite legal action

~By Sujit Bhar

Schools and their rules have come under the radar after the gruesome murder of Pradhyumn, a student of Ryan International in Gurugram. It is obvious that there is a huge disconnect today between school managements, teachers and parents of elite schools.

There are allegations that schools focus more on building a business and absolve themselves of all blame in case of an accident than providing a safe haven for children. The ancient guru-shishya parampara has largely been ignored and many have foregone their responsibility towards wholesome development of children. In fact, rules in certain schools are shocking, to say the least.

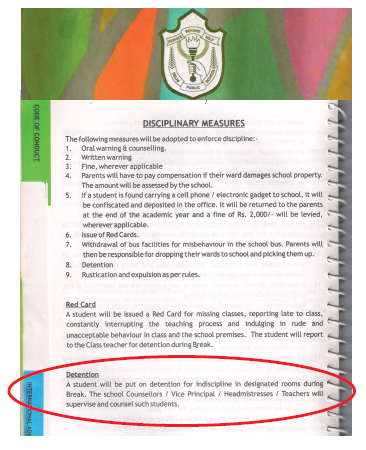

For example, in the student diary of Delhi Public School, RK Puram, there are some rules that will never hold in a court of law. Under the Disciplinary Measures section, Point 8 states that the school has created special rooms for detention, called “designated rooms”. While detention in schools is not a new phenomenon, a special room for the purpose is surprising. It seems like forced confinement. This cannot be done without the legal oversight of an adult. It is also in contravention of the parameters laid out in the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000.

Section 23 of the JJ Act, which deals with cruelty to a juvenile or a child says: “Whoever having the actual charge of, or control over, a juvenile or the child… causes him to be …exposed or neglected in a manner likely to cause… unnecessary mental or physical suffering shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to six months, or fine, or with both.”

The Delhi School Education Act & Rules, 1973, provides for only certain types of detention. It says: “37. (1) (a) (i) detention during the break for neglect of class work but no detention shall be made after school hours.”

India Legal sent a questionnaire to DPS principal Vanita Sehgal for clarification on this issue. Asked if a detention centre would not put immense psychological pressure on children, Sehgal wrote back: “…I would like to emphasise… that we at DPS RK Puram do not believe in punishments which will put psychological pressure on our children, as you can well see from the first few rules which are basically about counselling the children. Detention means being asked to stay in a classroom with a teacher during the break time and eating lunch/tiffin there. It is for 20 minutes. Students are, of course, allowed to visit the restroom and water coolers. Students may be asked to complete work they have missed or are counselled by the teacher on duty.”

However, the diary does talk about special rooms. Detention in a special room designated for such a purpose is tantamount to forced confinement and could result in psychological pressure and trauma for the child.

Another controversial point in the diary is “Swimming Pool Rules”. Point No. 13 states that the user of the pool would do so at his/her own risk and that the school will not be responsible for any kind of injury sustained by the user, nor for any accident. It adds that no compensation shall be awarded in case of any mishap. This is shocking as all swimming pool providers are legally bound to provide a certified lifeguard when it is open to the public (in this case, students). Sehgal’s reply to this was unconvincing. She said: “Rule 13, as quoted by you, is the basic rule of any swimming pool, to ensure that students do not indulge in any indisciplinary activity which may put their lives or others in danger. It does not mean that the school is absolving itself of any responsibility.”

The basic instruction for public swimming pools—as standardised by the Pune Municipal Corporation in 2012—says that for every 20 swimmers, there should be one trained lifeguard. The lifeguards should have completed a training course from a recognised institute.

Sehgal preceded this reply with the following explanation: “At the Swimming Pool we have trained coaches and licensed lifeguards in each shift. A trained nurse is on duty and an ambulance is stationed there at all times. In addition the Physical Education Department teachers are on duty along with a security guard.” If that is so, why does Point No. 13 state that the user of the pool would do so at his/her own risk?

Similarly, Apeejay School, Sector 16A, Film City, Noida, has outlined its discipline policy in its diary. Point No. 9 says: “The school reserves the right to isolate/suspend or expel a student with or without warning for any act of indiscipline and gross misconduct.” India Legal’s questionnaire to the school asked how it intends to “isolate” any student and put the blame on him in case of gross misconduct by a section of students. Till the time of going to the press, there was no reply from the school.

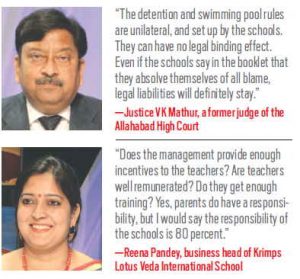

India Legal’s sister concern, APN, recently took up the issue and several experts voiced their opinions. Justice VK Mathur, a former judge of the Allahabad High Court, said: “Detention and swimming pool rules are unilateral, and set up by the schools. Even if the schools say in their booklets that they absolve themselves of all blame, legal liabilities will definitely stay.”

India Legal’s sister concern, APN, recently took up the issue and several experts voiced their opinions. Justice VK Mathur, a former judge of the Allahabad High Court, said: “Detention and swimming pool rules are unilateral, and set up by the schools. Even if the schools say in their booklets that they absolve themselves of all blame, legal liabilities will definitely stay.”

Sadly, schools also lack a humane touch. Jyoti Thakur, mother of the late Pradhyumn, made a startling revelation. She said: “My son died there, but nobody from the school ever called to find out how we were. I had called the school, no teacher even talked to me.”

Dr Loveleen Kakkar, ex-additional secretary, Women and Child Development ministry, Madhya Pradesh, said that there were laws aplenty on this, but there is no implementation. “Are we creating a safe environment for children?” she asked.

Dr Bharti Ali, Co-Director, HAQ Centre for Child Rights, and a parent, had a different take on this issue. “Why do we accept such regulations that will, obviously, not pass the test of law? We accept the fact that our children are in a famous school and our position in society moves up,” she said.

Another perspective was shown by Reena Pandey, business head of Krimps Lotus Veda International School. She asked: “Does the management provide enough incentives to the teachers? Are teachers well-remunerated? Do they get enough training? I would say the responsibility of the schools is 80 percent, while that of parents is 20 percent.”

It is obvious that there is a need for more parent-management meetings and for schools to lay down rules based on these inputs. After all, the safety of a child, the nation’s future, cannot be left to fate.