Above:Most of the Aravalli ranges are protected by the PLPA. Photo: Kh Manglembi Devi

The move by the Haryana government to amend the Act creates a storm, with environmentalists saying it will be an ecological disaster

~By Vipin Pubby

Haryana has the dubious distinction of having the second lowest forest cover in the country after Punjab. Both states, which were left with patches of forests along the Himalayan foothills following the carving out of Himachal Pradesh in 1966, have been keen to get the Punjab Land Preservation Act, 1990 (PLPA) amended to use protected land for commercial purposes.

The Forest Report 2015 issued by the Forest Survey of India pointed out that Haryana’s forest cover was 3.58 percent of its total area, out of which 90 percent forest falls in south Haryana in the Aravalli range. The move to now review the status of the land, close to the Delhi-NCR area, has kicked off a storm with environmentalists saying that such a review would be disastrous for the ecology of the region.

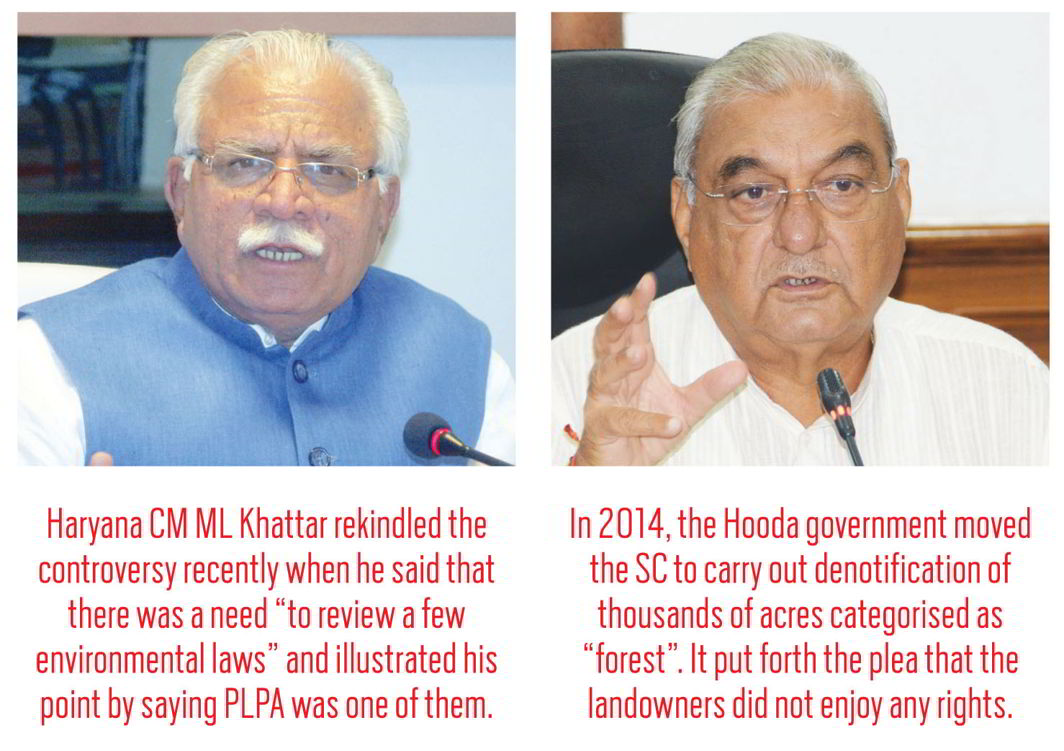

The controversial move for a review was made by Haryana Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar himself recently. However, the move is not new as his predecessor, Bhupinder Singh Hooda, too had initiated such a move. Their common argument is that the PLPA is a law over a hundred years old which has several flaws and is hampering development. They also argue that the law neither helped in recharging the land nor increasing the forest cover.

POLLUTION CONCERNS

Since most of the Aravalli ranges, particularly those closer to the NCR region, are protected by the PLPA, environmentalists are crying themselves hoarse as any relaxation would only add to the already gigantic problem of pollution in the region. There are strict restrictions under Sections 4 and 5 of the PLPA on any non-forest activity in 10 districts of Haryana, including Gurgaon and Faridabad—20,345 hectares of the total 27,304 hectares of Aravalli land in these districts are notified under the PLPA.

Khattar rekindled the controversy recently when he said there was a need “to review a few environmental laws” and illustrated his point by saying that “one such example is PLPA. It is a 100-year-old Act and thus needs a review. While there are many areas that still need to be preserved, development has taken place in a few areas. Our government is open to review the Act as per its relevance in the current scenario.”

Earlier this year, the state government had directed 10 districts to verify the status of land notified under the PLPA. The districts involved in this exercise were Gurgaon, Faridabad, Panchkula, Ambala, Yamunanagar, Mewat, Palwal, Rewari, Mahendragarh, Karnal, Jhajjar, Rohtak and Bhiwani.

A former conservator of forests said that the main reason for demanding a review is that land sharks have purchased huge chunks of land illegally in these areas and now want to make commercial use of the land. It could be for mining or real estate. Power lobbies of these landowners have been forcing politicians to get the law amended on the grounds that it has not served the purpose of recharging the land or increasing the forest cover.

He further said around one lakh hectares fall under the Aravallis in southern Haryana. More than a quarter of it is identified as forest under Sections 4 and 5 of the PLPA and around 62,000 hectares have been identified as Natural Conservation Zones (NCZs). Another 12,800 hectares are under the “yet to be decided” category.

In 2014, the Hooda government had moved the Supreme Court to carry out the denotification of thousands of acres of land categorised as “forest”. It put forth the plea that due to the “forest” tag, the landowners had “ceased to enjoy any rights”, including using plots for agricultural purposes. “Thus, their proprietary rights have been taken away without any compensation,” the government had then argued.

Now, the Khattar government appears to be concurring with these views. The chief minister said that sand mining shouldn’t be banned. “Mining shouldn’t be restricted completely as it raises the level of rivers, which further leads to flooding. To avoid flooding, there is also a need to recharge groundwater,” he argued.

The Haryana government has constituted a committee under the chairmanship of the divisional commissioner of Gurgaon to evaluate the status of areas in the Aravallis covered under Sections 4 and 5 of the Punjab Land Preservation Act (PLPA), 1900. It is expected to provide a clear picture of the ground reality in the 1.25 lakh hectares of the Aravallis and has been asked to submit its report within a couple of months.

The Haryana government has constituted a committee under the chairmanship of the divisional commissioner of Gurgaon to evaluate the status of areas in the Aravallis covered under Sections 4 and 5 of the Punjab Land Preservation Act (PLPA), 1900. It is expected to provide a clear picture of the ground reality in the 1.25 lakh hectares of the Aravallis and has been asked to submit its report within a couple of months.

The committee can obtain all relevant government records from concerned departments and agencies to examine the status and land use of the areas marked as “forests” as of October 25, 1980. The committee would use revenue records to determine the land use status over the decades.

EFFECT ON THE ARAVALLIS

Environmentalists have, however, raised several red flags. They fear that a review of the PLPA could lead to denotification of a large portion of the Aravallis. They said that it would further dilute the forest cover as the revenue records are not clear. Large tracts in the Aravallis have not been clearly demarcated as forest areas.

The Haryana government also submitted an affidavit to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) on January 6 this year claiming that the Aravalli plantation areas are “not forest”. This too raised the hackles of environmentalists who said if the state government’s claim was accepted, nearly 70 percent of the already meagre forest cover in the state would be out of the ambit of “green cover”. The affidavit, environmentalists point out, was “misleading” as the plantation areas of the Aravallis are recorded as “gairmumkinpahar” (non-cultivated land) and considered “deemed forest”. The affidavit said that clearance under the Forest Conservation Act, 1980, was not applicable to Aravalli plantation areas for non-forest activities.

While environmentalists say that the affidavit was meant to mislead the tribunal and protect the illegal mining happening in the “deemed forest” areas of the Aravallis, government sources assert that the PLPA was framed more than a century ago and has become outdated. Due to the stalemate caused by the issue before the apex court and the NGT, several projects have been held up. For instance, it is ironic that permission to construct houses in the sprawling Green-fields Colony, Faridabad, which was planned nearly half a century ago, has been withheld despite the fact that over 60 percent of houses have already been constructed. The ban on mining has prompted officials to not allow digging even on allotted residential plots.

The Punjab government too had approached the Union government to seek exemption of the Kandi belt bordering Himachal Pradesh from the ambit of the PLPA. Former chief minister Parkash Singh Badal had said that the PLPA had affected the overall development of the sub-mountainous kandi belt as there was a ban on tree felling and forest clearance in the area.

There appears to be some merit in the arguments of both sides. Huge changes have taken place in the past century and there is a need to revisit the provisions of the PLPA. Care needs to be taken so that the ecological cover is not disturbed any further in the eco-fragile areas but at the same time genuine requirements have to be met.