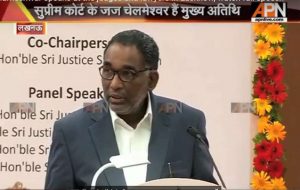

Above: A grab of the State Level Judicial Officers’ Conference 2017 held in Lucknow. Courtesy APN

A first-ever such gathering of judicial officers in UP saw Justice J Chelameswar bring up critical issues

~By Sujit Bhar

Issues about how to improve the functioning of the subordinate judiciary, improve its image and reduce the humongous pendency have been hanging fire for a long time. Solutions aren’t easy, but the first step towards it was in accepting that the problems exist and in addressing it at a formal forum.

The State Level Judicial Officers’ Conference 2017 for HJS officers, held under the auspices of the Allahabad High Court, at the high court auditorium in Lucknow on September 9 and 10 proved to be the right forum.

The function was presided over by the Allahabad High Court Chief Justice Dilip Babasaheb Bhosale and APN, the sister concern of India Legal and the most popular news channel of UttarPradesh. APN had exclusive rights to it.

Present on the occasion, among others, were Supreme Court Justices J Chelameswar, the senior-most judge, and his brother judges AK Sikri, RK Agrawal and Ashok Bhushan.

Discussions and deliberations resulted in new thoughts and newer passages. Not only was it the first ever such conference in this state, it was an exercise in administrational critique that revealed problems and offered some solutions.

As this was mainly a look into the functioning of the subordinate judiciary, the basic things discussed were pendency and how to tackle that, the attitude and bearing of judges and how this would affect the common man, on how the subordinate judiciary is actually the real face of the Indian judiciary for the common man and on the lacunae that need to be filled in order to provide speedy and quality justice.

Justice Chelameswar, in his long speech, brought up a few very critical issues. They, of course, included pendency. But he also highlighted the fact that the government is burdening the judiciary by forcing it to handle the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA), of which the senior-most judge of the Supreme Court is expected to be the executive chairman. The Chief Justice is the ex-officio patron-in-Chief. He said there needs to be a system evolved, within the judicial ambit, to handle this.

He also was critical of the government’s policy of having the chief justice of a court always from another state. This, he said, creates major administrative problems for a new chief justice, who is not aware of the peculiarities of the court he is travelling to, to head. He said this needs debate.

The general theme was that the subordinate judiciary must be better than what it is today. The common litigant in India is totally averse to going to a court of law, because the experience he/she has over there is painful. Justice Chelameswar said that this must change. The image of the judiciary, especially starting from the subordinate judiciary, must be litigant friendly. Other judges too talked about the need for being sensitive towards litigants, especially the victims, so they do not lose faith in the judiciary.

Here are some of the opinions expressed by the legal luminaries at the conference.

Justice J Chelameswar

The senior-most judge of the country started with history. He said: “The history of the country for the last 100 years and the history of this court (the Allahabad High Court) are inextricably intertwined. When your chief justice asked me to come here for this function and asked me to give the inaugural address, I was a little hesitant. The reason was that normally inaugural addresses, I think, are supposed to be condescending affairs, advising others, and I was not sure if I had the ability to advise others. But suddenly I realized that yes, at least for one reason I can do that. I don’t see any face here in this gathering which appears to be older than mine. I am retiring in just a few months.

The senior-most judge of the country started with history. He said: “The history of the country for the last 100 years and the history of this court (the Allahabad High Court) are inextricably intertwined. When your chief justice asked me to come here for this function and asked me to give the inaugural address, I was a little hesitant. The reason was that normally inaugural addresses, I think, are supposed to be condescending affairs, advising others, and I was not sure if I had the ability to advise others. But suddenly I realized that yes, at least for one reason I can do that. I don’t see any face here in this gathering which appears to be older than mine. I am retiring in just a few months.

“Since this is essentially a programme meant for the members of the subordinate judiciary I will start with an idea I was wanting to project and has already been covered by my brother judge Ashok Bhushan.

“He was right. The ultimate face of the Indian judiciary is the face of the subordinate judiciary of this country. The common man knows the local munsif as they were known earlier, the junior and senior civil judges of today and the district judges. The judges of the high courts are relatively less known to the common man. Supreme Court judges were not known at all till about 20 years back, till we developed this new culture of inviting Supreme Court judges to the high courts, which has become a weekend affair in some of the courts and for some of the honourable judges.

“So the common man makes his assessment of the legal system through his perception of the subordinate judiciary day in and day out, if he has a need to interact. And I must say this is not a very pleasant experience. Given the opportunity, I don’t think many people will have anything to do with the judiciary. Running around the courts is not a pleasant experience. We are all excellent people no doubt about that, but the system is such that it becomes very painful for anybody to approach the legal system.

“The amount of time consumed in the resolution of a dispute, civil or criminal, varies from state to state, from high court to high court and from system to system in this country. But in no state of the country is it a pleasant experience. Maybe the time-scales are slightly different… at some high courts criminal appeals take 2-3 years, in some more. The idea is not to blame anybody. The idea is to project a different point.

“Naturally, a citizen who has had the occasion or a need to interact with the judiciary would not be very happy to do so. He is compelled to do it. But that is not an answer to the problem we are talking about.

“What does this system need (to improve)? In my opinion, and I am sure that it is a philosophically established view when we talk about liberty, that the purpose of securing independence and the purpose of giving ourselves this constitution is to secure liberty for the people of this country. And liberty cannot be secured unless there is an impartial judiciary in society. Therefore, there is the need for a judiciary at various levels.

“Imagine a situation where there is no judicial system, where the rights and obligations of the citizen depend purely on the mercy of the legislature or the executive government. I don’t think it will be a pleasant society or a society where liberty is assured. There is nobody to verify whether the action of the state is just, reasonable, fair, legal and libertarian. It is only the existence of a strong judiciary that can ensure these.

“When I am talking about liberty, let there be no illusion that only the high courts and the Supreme Court talk about liberty. It is the lowest court, the magistrate of this country, who is the first officer who ensures the liberties of the people. And the constitution ordains that any man arrested is required to be produced before the magistrate as early as possible. Only after his (the magistrate) touching the matter does the question come before the other courts.

“If that is the purpose of the system, then judicial officers of the system have the great responsibility of portraying hope to the people, of giving justice to the people at the most elementary level. This can only happen when we have a well-informed, well-trained subordinate judiciary, a judiciary with impeccable integrity.

“The question of integrity is essentially a personal trait. Individual character is moulded by the character of society, contemporary social values and values that society cherishes at any given point of time. It also depends on how much of these social values are imbibed by those individuals. Also, what is the background in which the individual was brought up, what values were given to him in his childhood by his own family, the society around him, the educational system which got him to become a judicial officer, etc.

“This is essentially a personal endeavour. But coming to the question of the efficiency of the judiciary… it is a mixture of two things: the effort of the individual and the efficiency of the system within which the individual is working. The efficiency of the system can always be improved by appropriate programmes, a training programme such as this one. I see two programmes to be debated here. Judicial discretion and the need to sensitise the judicial offices about the relevance or importance of mediation. They are relevant.

“On the second topic, I was an ardent believer for the last 20 years. By virtue of being the senior-most judge of the Supreme Court today, the established fact is that generally the senior-most judge is called upon to act as executive chairman of the legal service authority.

“I have consistently taken the view (for the last 20 years) that no judge at any level should be compelled to be associated with this programme, because it is creating an additional burden on the judicial system. If Parliament wants to have this legal service authority in this country, it has the power to make such a law, but Parliament, in my view should create an independent mechanism. It should be independent not in the sense of not being amenable to judicial supervision, but independent in the sense of sharing the workload.

“I have seen in three high courts in which I have had the privilege of being associated with— two high courts as chief justice and one high court as my parent high court—judicial officials who had the freedom and liberty to discuss freely with me (most of them, especially back home in Andhra Pradesh), used to tell me woeful stories of all the pressures they were under when they were called upon to discharge these functions. My idea is not to point fingers at the system, but since we are talking about mediating, the idea is this: essentially, we are not being able to handle the problem.

“About 12 years back on one of the occasions when Justice Ruma Pal as executive chairman of the service visited the high court, I was called upon to speak. So I mentioned this. I said it’s something like a bypass, nobody celebrates a bypass, it’s something to be endured, that’s all. Similarly, these legal services are an acknowledgement of our inability to cope with the problem. I was talking to the chief justice (of Allahabad High Court, Justice Bhosale) and came to know that the total pendency of this high court is about 9 lakhs. I am told and the pendency in the state is 6 million. So one can understand what kind of pressure it creates. What are the reasons of this pressure is a different matter.

“We may not be the only people responsible for pendency. Most often everybody finds fault with us. ‘Once we go to the court it takes 20 years, the judiciary gives adjournments etc.,’ they say. An incident happened when once I was in Kerala, sharing the dais with the then deputy chief minister of Kerala. The inevitable accusation came: Courts take long time to adjudicate. When my turn came to respond, I asked the honourable gentleman—he was also the law minister apart from being the deputy chief minister. I asked ‘Mr Minister, I would like you to go back and check out what was the total manpower engaged in the bureaucracy by your state in 1955 when your state came into existence and what is the current manpower of your bureaucracy and compare it with the figures of the judicial officers and compare the ratio of the population against the judiciary and the bureaucracy. You can then compare the ratios.

“It is a well known fact in this country that the budgetary allocation for the judicial wing of any state doesn’t exceed 1.5 to 2 percent. Add to that the fact that the number of courts has remained more or less stagnant. People still blame us. I can understand the litigant blaming, because he is not worried about all this logic, he is simply worried about his case and the result, but those who hold responsible positions, those who believe to be the intelligentsia of the country, those who write columns in newspapers, none of them really spend time to analyse where exactly is the problem and what is the solution.

“It is in this background that we have to work. So programmes like mediation, arbitration so on and so forth and other dispute resolution systems are bound to come up. And this is not peculiar to India even countries with greater resources and lesser population also face this problem of pendency in their courts, but the periods of pendency might be much lower. But the problem is a universal problem.

“There is a need to explore the possibilities of finding a solution to this problem within the limitations that are imposed on us. We still have to strive to improve our system and that necessarily means improve our skills, our abilities, our knowledge of law and a programme like the current one undertaken by you certainly goes to an extent in improving the skills of the subordinate judiciary.

“As I was mentioning, I am in an institution whose history is intertwined with the history of the country. Taking the history of the country in the last 45-50 years—that’s around the time when I got into the study of law—the election dispute of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had a stage set right in this high court. The rest is history. What is relevant in this gathering of judges is that that incident marked a certain high point in the history of Indian judiciary.

“The fearlessness of a judge of a high court to deal with the election dispute of the most powerful office holder in this country, and dealing with the prime minister’s election petition (1975) required absolute commitment absolute courage, uninfluenced by any kind of extraneous considerations. That great judge was Justice Jagmohanlal Sinha. But my purpose of mentioning this is not only to remember the judge but to examine the system. What happened in the next 50-odd years. One of the fallouts of that judgement was the formulating of a policy of the government of India where as a rule chief justices are required to be from outside the state.

“There are arguments both in favour of and against this policy. Every policy has its own strengths and weaknesses, but after some 40 years of its introduction I think it is time to take stock of what the merits and demerits of this policy are. Whether it has achieved any good purpose is a question which is required to be debated at least.

“I will tell you the negative aspect of this policy, because I have had the privilege of being the chief justice of two high courts. And quite a long stint of about four and-a-half years. Mine is an exception, the average tenure of a chief justice of this country is about one year. When a judge goes to another high court as chief justice, it would take some time for the chief justice to understand the local conditions, the local problems—the administration, I am not talking about the law part—a chief justice needs to give attention towards administration and this requires time. A judge rising to be chief justice of his own high court has the advantage of knowing the system for 25-30 years. So from Day One he can set on his job trying to address the problems. But a transferred chief justice has to start from scratch. For any chief justice, this is a huge problem.

“When I went as chief justice to the Gauhati High Court, it had seven benches. Today, of course, it has seven high courts for seven states. Then the administrative rules were peculiar to the court. There were rules for each bench. It was very complex. To understand all this for an outsider it takes time. What is the purpose that this transfer policy achieved I still do not know.

“What was the reason given on that day for transferring the chief justice? The government of the day perceived that some of the chief justices are resorting to some unwarranted or some unwholesome practices. This argument always baffled me. In that case why not have a chief minster from outside the state? Does the chief justice enjoy a greater power than the chief minister?

“I am not talking about any particular chief minister. I am talking in general of the office. The ability to resort to unwarranted or unwholesome practices is much more there, with the kind of decision making authority which vests in them. Even this transfer (of chief justices) is not part of the test of the constitution; it becomes the policy of the government. The policy was introduced in 1984. Irrespective of the name of the political outfit which was in power on this one issue there was unanimity. Nobody wanted to change it. I say at least please debate it. I don’t think there can be a better forum where I can say this.”

Justice AK Sikri

He detailed the different sections being discussed in the forum, and then said: “These topics are varied, about pendency, speedy justice, etc., but if you look at it from a different angle there is a common thread. For us judges, our main work is to decide cases and do this the best we can. In this process we have to think what is role of judges in the judicial system. If you look at this carefully you will find a connection in all these issues. I say this conference was to tell you how to develop judicial cases and how to gain knowledge. More important than that, however, is how to adopt a good work culture.”

He detailed the different sections being discussed in the forum, and then said: “These topics are varied, about pendency, speedy justice, etc., but if you look at it from a different angle there is a common thread. For us judges, our main work is to decide cases and do this the best we can. In this process we have to think what is role of judges in the judicial system. If you look at this carefully you will find a connection in all these issues. I say this conference was to tell you how to develop judicial cases and how to gain knowledge. More important than that, however, is how to adopt a good work culture.”

He explained about work culture, by saying: “It is about attitude. It is not more cases in less time. It is about good justice, a good outlook behind all this.”

He explained his point by saying: “Even an interim order has great importance vis-a-vis what effect it can have on the main case. This has to be seen. If the interim order has not been good then it will have an effect on the final case. I have been in the Supreme Court for over four and-a-half years. As a high court judge I used to think why so many bail and revision matters come up. Now I see they also come to the Supreme Court. The numbers may be less, but they do.”

The point that Justice Sikri wanted to make was that this need not be, if the subordinate judicial officers apply their minds in dealing with each and every case. “What happens when such things occur?” he asked. “There are delays in main cases,” he answered. “So discretion is needed down the line.

“As far as mediation is concerned, what is our role as judges? The simple answer is deciding cases. Today, is it our fault that there are 3 crore pending cases? We can say that it is not ours. We do not generate the cases, they come up from society. So we can say that pendency is not because of us. But can we see this just as a simple function of having to decide more cases? I say no. We have to do justice with the people also, not only decide the case. We have to go from judging to “justicing”, or doing justice. We need to sensitise the judges at all levels. And that is the reason for this conference.

“While justice delayed is justice denied, in converse justice hurried is justice buried. We have to find a balance between the two. We should not blow our own trumpets, we should ask the man on the street how we have been. They say that the bar is the judge of judges. What we do is discussed. But even the field of view of the lawyers is limited. I think the view of society has more value.

“You may think that you have handled a hundred cases efficiently, but you have not paid notice to just a few and so you think you deserve an A certificate. But remember, for that person who may have been a victim, the other hundred cases have no value. He is concerned about his or her case only. What society thinks of you has more value. A quality judgment will ensure that unnecessary appeals are not filed.

“Many times your conclusions may be correct but the way the subject is approached, the way issues are approached may not have been prefect. There may be loopholes in that and that will result in filing of appeals,” he said.

Justice RK Agrawal

“The subordinate judiciary is the bedrock on which stands the entire edifice of justice. It is undoubtedly the foundation of our judicial system. Being situated at the grassroots levels of society, it symbolizes the epitome of justice. To be a judge is a privilege and we have to remember that the authority to govern has certain duties and obligations attached. The first and foremost attribute you must inculcate as a judicial officer is the necessity of conducting yourself in such a manner both inside and outside the court so as not to provoke any critique.

“The subordinate judiciary is the bedrock on which stands the entire edifice of justice. It is undoubtedly the foundation of our judicial system. Being situated at the grassroots levels of society, it symbolizes the epitome of justice. To be a judge is a privilege and we have to remember that the authority to govern has certain duties and obligations attached. The first and foremost attribute you must inculcate as a judicial officer is the necessity of conducting yourself in such a manner both inside and outside the court so as not to provoke any critique.

“You should not be carried away by the importance of your position and the power you wield. You must remember that the power you hold is limited and must not be exercised beyond your jurisdiction. The conduct of a judicial officer has to be above reproach. A judge has to be punctual, patient, courteous, impartial and fearless. You have to be firm, but not rude.

“You have to grapple with the problem of mounting arrears and think of remedial measures to deliver speedy justice to the common man. All of you have to concentrate on docket management. In addition you have to devise techniques with case management, including alternate dispute resolution techniques such as conciliation and arbitration. Time has to be used effectively and much stress should not be laid on procedural aspects. We know that procedure is merely a handmaid of justice. The adjournment culture should be dealt with by strong hands by courts.”

He talked about the usage of free legal aid. He also talked about effective leadership and management at all levels. He also talked about why it is essential for the incorporation of IT in the judicial system. He said: “Efforts are already being made to make all paperwork of courts paperless by adopting e-filing and also by running e courts. The use of WhatsApp a social networking app by Allahabad High Court for serving of summons is an innovative step. These are welcome changes.”

He gave a warning as well. He said; “We should not see the judiciary’s transformation as an end in itself. It must be understood that the judiciary can play its part effectively when the citizens have faith in its integrity and in the impartiality of judges and the fact that due process is afforded to all who come before the courts.” He talked about the discipline that needs to be imposed by the judiciary on itself to earn the respect and faith of the public.

He said: “You will be aware that pursuing claims in the lower courts is a difficult process, yet the litigants do so because of the faith they have in the system, that the judicial system is impartial and the judges are trustworthy. This we can ensure by providing greater resources and great financial commitment to the lower courts.”

He also advised the lawyers to guide the litigants properly through the complicated process.

Justice Ashok Bhushan

“The judicial affairs of the Allahabad High Court carries an enormous burden, what with the state of UP having the largest population and the litigation enormous as well. Hence there is greater need for efficiency.

“The judicial affairs of the Allahabad High Court carries an enormous burden, what with the state of UP having the largest population and the litigation enormous as well. Hence there is greater need for efficiency.

“We should utilize each and every moment allowed to us to do as much work as possible. At the time of laying down office, there must be no regret that if more time was available we could have done more, with more efficiency and perfection. It is the present moment that we have to give our best to society.

He talked not only about the judges’ conduct inside and outside courts but also of judicial officers, inside and outside courts. “This is especially pertinent to the district judiciary. It is at this lower level that the vast majority of cases are heard and decided. Practically civil courts are the final courts in 75 percent of all cases. The perception of the judiciary in the eyes of the ordinary citizen is shaped by the working of the subordinate judiciary. Therefore an effective and modern system at the level of the subordinate judiciary is essential.”

He talked about how the power in the judicial system can be abused. “One has to be careful to not let that happen,” he said. He talked about how a fresher in the system may be bewildered with the huge judicial powers at his disposal and it would be easy for him or her to misuse this.

He also talked about how the subordinate judiciary has to stay abreast of the happenings and the decisions of the upper judiciary and the judgements and observations therein. “Because, if you don’t learn, you will be making mistakes and the litigant will carry these mistakes through his appeals into upper judiciaries. This is important especially for the vulnerable ones, for those who have suffered juvenile crimes.”

Allahabad High Court Chief Justice Dilip Babasaheb Bhosale

“Performance indicators will change in the pendency and for this the cooperation of the local bar is essential. However, administrative indicators will depend upon the staff and we are in the process of striking a balance between the performance parameters of judicial and administrative areas. I feel this conference gave a great opportunity to the judiciary to review the working of subordinate courts and tried to bridge the gap between expectation and performance. Keeping the theme in view, we selected topics for deliberations in four academic sessions. The primary aim was to critically explore the shortcomings in elevating the prestige and honour of the judicial institutions.”

“Performance indicators will change in the pendency and for this the cooperation of the local bar is essential. However, administrative indicators will depend upon the staff and we are in the process of striking a balance between the performance parameters of judicial and administrative areas. I feel this conference gave a great opportunity to the judiciary to review the working of subordinate courts and tried to bridge the gap between expectation and performance. Keeping the theme in view, we selected topics for deliberations in four academic sessions. The primary aim was to critically explore the shortcomings in elevating the prestige and honour of the judicial institutions.”

He talked about the sessions where junior judicial officials had their doubts cleared and made valuable suggestions for the improvement of the working of courts at all levels.

“Yesterday I highlighted the reluctance of district judiciary to grant routine bail and interim orders. We have noticed judges hesitate in passing decisive orders maybe for known or unknown fears. If advice of the brother judges of the high court is followed, I am sure the high court will not have to chastise the subordinate judiciary for their inability to adjudicate upon interlocutory applications. If proper orders are passed you need not carry any fear in mind and that will go a long way in reducing your burden and also the burden of the high court.

“Remember that the litigating public demands speedy and timely justice. Even from the point of view of the accused, the right to speedy trial is a fundamental right.”