The recommendation of the Centre to recruit transgenders in the Central Armed Police Forces bridges the gap since the landmark verdict by the Supreme Court on transgender rights in 2014. Is it feasible?

By Kaustubh Shukla

“Every individual soul is potentially divine.”

—Swami Vivekananda

Madhu Bai Kinnar was elected mayor of Raigarh, Chhattisgarh, in 2014. Earlier, Kamala Jaan had won the mayor’s election in Katni, Madhya Pradesh. Padmini Prakash is a news anchor while K Prithika Yashini is a police officer. Laxmi Narayan Tripathi represented Asia-Pacific at the United Nations. Joyita Mandal was appointed Judge, Lok Adalat, in North Bengal and Sathyasri Sharmila is a lawyer. They all have something in common: they are all transgenders. The Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in 2014 on their rights is an extension of its record in the past few decades in recognising fundamental rights like Equality (Article 14), Freedom (Article 19), and Personal Liberty (Article 21). The apex court has always kept individuals as its main focus, believing that rights and dignity of individual citizens culminate in the collective dignity of society.

Similarly, serving the nation as a part of the armed forces is a matter of great pride for a citizen. For transgenders and their families, such access would lead to similar dignity for the whole community. The recent recommendation of the central Government to recruit transgenders in the CAPF (Central Armed Police Forces) is a step in the right direction, but can it work on the ground?

Since the passing of its order in 2014, the Supreme Court issued a questionnaire to governments to ascertain its implementation. Many state governments still don’t have a welfare board for the socio-economic upliftment of the transgender community, a constitutional mandate for reservation or even awareness schemes. Against this background, the recent decision of the central government is a big step toward recognition and dignity for the transgender community. The word “dignity” finds a place in the Preamble of our Constitution. It also finds a place in Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and Article 3 of the European Convention Of Human Rights.

In the landmark NLSA Vs Union of India (2014), the Supreme Court while recognising the transgender community as the third gender in our country with legal and constitutional protection, discussed various other related issues. The Court held that discrimination and denial of rights, privileges, employment, etc, is violation of fundamental rights. It applied Article 14 & 21 of the Constitution, referring to “person” as a gender neutral term which covers transgenders and hence they are entitled to legal protection of law in all spheres, including employment as citizens. The judgment also states that transgenders are entitled to benefits of reservation available to the socially and educationally backward classes (SEBCs) and they have been denied rights under Articles 15(2), 15(4), 16(2), 16(4).

The government was also directed to take affirmative action for due representation in public employment, noting that although discrimination qua transgenders is still there, they are also citizens of our country and entitled to equal opportunity in employment.

In its 2014 decision, the Supreme Court also applied the Yogyakarta Principles, recognised by the United Nations and other various international forums. The Yogyakarta Principles broadly address the standard of human rights qua gender. The Yogyakarta Principles were drafted by distinguished groups of human rights guardians in the meeting held at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

The Supreme Court exhaustively referred to various articles contained in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966, The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 as well as the Yogyakarta Principles. Reference was also made to the legislation enacted in other countries dealing with rights of persons of the transgender community. Since there was no legislation in India at that time dealing with transgenders, the Supreme Court, under Article 51 read along with Article 253 and relying on various precedents enshrined in its earlier judgments, including Vishaka, issued directions to the central and state governments which were required to be implemented till the enactment of legislation.

Unlike other countries, in India transgenders have cultural and historical importance, referred to as Shiv-Shakti. Even Arjuna as Brihannala fought valiantly with the Kauravs in the Virata War. The transgender community in India was historically always given much respect but that is no longer the case. After the enacting of the NLSA (2014), the central government enacted The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019. The Act codified various provisions for protection and privileges of transgenders. Section 3 of the Act prohibits discrimination or denial by persons or establishments of employment or service to transgenders. It also elaborately discussed many other forms of discrimination and denial. Chapter 3 of the Act gives self-perceived gender identity to transgenders. Chapter 4 of the Act is an obligation on the government to make sure of the effective participation of transgenders in all the spheres of society with various welfare schemes and measures. Similarly, Section 11 provides a grievance redressal mechanism wherein every establishment shall have a complaint officer dealing with any complaints of discrimination. Chapter 8 of the Act deals with offence and penalties. The chapter is surprisingly silent on punishment for denial of employment by any person or establishment on the ground of being transgender. The Act no doubt places an obligation on the establishment (i.e. public or private institutes, states and the central government) not to deny or discriminate in the matter of employment, but there is no punishment if it is not adhered to. The Act in many areas requires review to make it in consonance with the NALSA 2014 judgment of the Supreme Court.

The recent recommendation by the Home Ministry to the CAPFs for including transgenders in posts of Assistant Commandants is a positive move but raises many questions. The DoPT (Department of Personnel and Training) has already asked the central government to include “transgender” as a third gender in all application forms in the process of recruitment to various posts. The Civil Services Examination Rules, 2020, have notified inclusion of “transgender” as a separate category but the road ahead is difficult.

The CAPF or the army or police forces have a different psychological way of administration in comparison to other civil services. Recruitment of transgenders in the CAPF will face some difficulties due to ground realities regarding atypical command philosophy. The recommendation to include transgenders as assistant commandants is a top-down approach, whereby in any armed forces when it comes to authority and control, command is a very different concept.

Just by clearing UPSC exams and being an officer, one cannot impose his or her command over soldiers. In actuality, a directly appointed officer after completing training goes to his unit, where after familiarisation and pre-induction training with soldiers, gets independent command of the company/unit. It is the soldiers who submit to commands by the officer if they find him/her worthy. We have seen command failure resulting in mismanagement and, in extreme cases, fratricide. The question is not about the ability or legal right of transgenders; it is about a drastic cultural change. The basic command structure of our forces, which comprises 10th to 12th pass soldiers and the subordinate officers who are graduates and often come from conservative rural backgrounds, may see these cultural changes as offensive to their social and religious beliefs and create resentment against those commanding them. Like the case with women as commanding officers in the Indian Army, which took some time and after the Supreme Court verdict in 2020 became acceptable to lower ranks, the government order on transgenders needs to be introduced in a calibrated way. Before its implementation in the armed forces, it needs to be implemented effectively in all other sections of society, allowing it to get naturalised as part of society over a period of time, so transgenders are accepted as normal citizens like doctors, engineers, collectors, judges etc.

Only once they have become a common social reality, should they be brought into the armed forces and that too starting from constabulary to subordinate command and then to senior command in the normal span of time. This issue of induction of the third gender in the CAPF is not just a legal one, it is also a social issue which needs to be carefully introduced before elevating the third gender as officers.

—The writer is Advocate-On-Record, Supreme Court of India

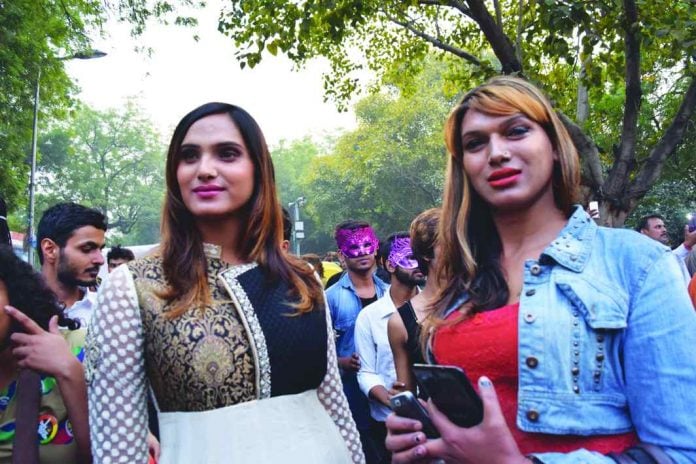

Lead picture: Lembi Kh