Despite the crying need for speeding up and modernising the grossly inefficient justice delivery system, a large chunk of the meagre funds allotted in the Budget remains unused

~By Usha Rani Das

Budget allocation for the judiciary is a serious concern. In so far as the Supreme Court is concerned, the government is not providing sufficient budget and, time and again, the Chief Justice has to intervene to seek sufficient allocation of Budget,” former Chief Justice of India (CJI) P Sathasivam had said in his farewell speech in 2014.

What the former CJI and the current governor of Kerala said in 2014 is something that CJIs and judges of the apex court and various high courts have mentioned before and that too repeatedly—the measly budgetary allocation is grossly inadequate to improve infrastructure, set up new courts and appoint judicial officers, all of which are imperative to bring down the massive pendency rate of cases, from the apex court all the way down the ladder.

To get an idea of the magnitude of the problem, consider this—there are more than 3.3 crore cases pending in courts across the country, many of them for over 10 years. Of these, around 60,000 are in the Supreme Court, a little over four lakh in various high courts and about 2.9 crore in the district and subordinate courts. Simple logic suggests that with more courts and more judges, the problem could be tackled easily. But for that, you need money and the judiciary has scarce resources. For decades now, the judiciary in India has survived on a negligible allocation that has ranged between 0.2 percent and 0.4 percent of the annual budget.

The problem of meagre allocation of funds is compounded by under-utilisation of the available funds. The Union Budget for 2017-18 had earmarked Rs 1,174.13 crore for the judiciary. The Supreme Court was allocated a sum of Rs 247.06 crore, a marginal increase of Rs 4 crore from last year and included ad-ministrative expenditure, salaries and travel expenses for the chief justice and other judges, security personnel and related needs like stationery, office equipment, security equipment, maintenance of CCTV and printing of the annual report of the Court. The apex court’s budget is prepared by its registrar general, which is forwarded by the law ministry to the finance ministry. The same process is followed by high courts who forward it to the state governments. However, high courts also have the additional responsibility of preparing budgets for lower courts within their jurisdiction.

The primary responsibility of infrastructure development for the subordinate judiciary lies with the state government. The central government also releases additional funds under the Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS) for development of judicial infrastructure. The law department sanctions establishment of new courts and the home department releases funds for creation and maintenance of judicial infrastructure.

According to latest statistics gathered by the Supreme Court, the total pending cases in the subordinate courts across the country has risen from 2.68 crore in 2013 to 2.71 crore in 2015. But for dispensation of these cases, there is not sufficient infrastructure—judges, staff supporting them, lawyers, courtrooms, and so on—due to which this pendency increases every year. There is a shortage of 5,018 courtrooms in the subordinate judiciary. As of January 2016, there are 15,540 court halls to cater to the sanctioned strength of 20,558 judicial officers. There is a shortage of 8,538 residential quarters for accommodation of judges in the subordinate courts. Also, there are currently 41,775 vacancies of judges, magistrates and judicial officers.

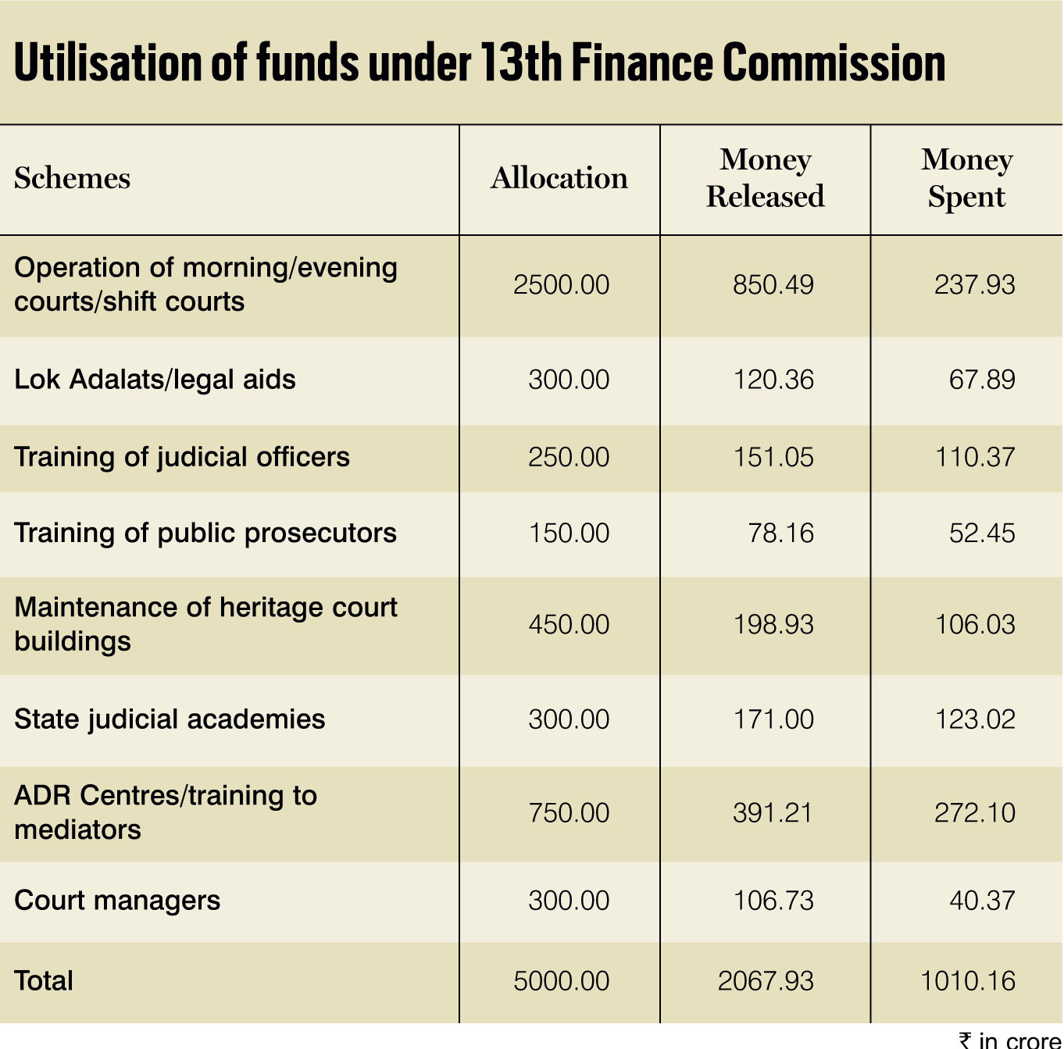

To solve this, the Budget had proposed an outlay of Rs 630 crore under the CSS for constructing 600 additional court halls and 350 residential units in the coming year. But will this work? The answer can very well be guessed by analysing the performance under the 13th Finance Commission Grant. In 2010, the Commission had given a special grant of Rs 5,000 crore spread over five years to both the Union and state governments to be utilised for the following purposes—operation of morning/evening/special shift courts, establishing alternative dispute resolution centres and training of mediators/conciliators, Lok Adalats, legal aid, training of judicial officers, state judicial academies, training of public prosecutors, creation of posts of court managers and maintenance of heritage court buildings. Data gathered from the ministry of law and justice shows that at the end of the five-year period, funds of Rs 1,010 crore, a mere 20 percent, were ultimately utilised (see Table 1).

As the initial funds are not utilised, the rest of the funds that are due are held up which adds to a cumulative deficit in the judiciary’s budget every year. Rupinder Singh Suri, senior advocate and former president of the Supreme Court Bar Association, told India Legal: “Has the judiciary utilised whatever funds it has been allocated? The answer is ‘no’. They have not even spent the meagre amount that has come. If you spend less than what has been allotted to you, then next year that much less amount is allotted to you in the budget. How can they justifiably ask for more money when they have not spent the amount allotted properly and sensibly?”

As a result, the judiciary keeps begging the executive for the funds and the funds don’t come. A closer look at the financial audit reports of some representative states paints a scarier picture. In Uttar Pradesh, the state government had planned to construct 500 courtrooms and 400 residences for judicial officers in the district and subordinate judiciary in the Five Year Plan (2012-17).

The 2016 report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India for Uttar Pradesh found major deficiencies in the utilisation of the funds. An expenditure of Rs 827.50 crore was incurred on construction of courtrooms and residential accommodation for judicial officers during 2011-16. The state government could utilise only 33 percent (Rs 401 crore) of the budget allocation for construction of courtrooms and residential buildings. It could only complete construction of 37 percent courtrooms and 28 percent residences. Against the Plan outlay of Rs 1,093.00 crore during 2012-16, only Rs 699.86 crore (64 percent) could be spent.

This is bound to affect the smooth functioning of the courts. The report states: “Lack of effective monitoring by the government and inability of the executing agencies to speed up the slow pace of work were the main reasons for this unsatisfactory state of affairs.”

Though, as per the directions of the Supreme Court, it was mandatory to provide residential accommodation to each judicial officer, there is an acute shortage. Only 107 residences were available against the required 234, thereby leaving a shortage of 127 residences (54 percent). The report added: “…the shortage of residences is likely to continue in future, as against 140 court rooms under construction only 78 residences (56 per cent) were being constructed. The construction of residential accommodation and court rooms was marred with deficiencies such as lack of supporting infrastructure, inadequate survey, clear site not being available, delayed approval of maps, slow pace of work, etc.”

The story is repeated in almost all the states. The 2016 audit report of Odisha shows that the overall percentage of utilisation of funds received during 2013-16 was 62.20 and the percentage of utilisation of funds received under the State Plan was nearly 66. However, utilisation of funds under the 13th Finance Commission was only 31 percent (see Table 2). Of the sanctioned 180 new courts, construction of buildings for 140 courts was taken up, out of which 125 projects were completed and 15 were in progress. However, no action was taken for creation of infrastructure in respect of the remaining 40 new courts.

The audit report of Assam for the year ended March 2017 also shows that only Rs 209.96 crore was utilised out of the total grant received of Rs 312.10 for administration of justice.

There have been several instances that have highlighted gross mismanagement of funds of the judiciary. In Nagaland, the government is said to have allegedly withdrawn Rs 22.42 crore from the state exchequer for the construction of judges’ bungalows but no area has been earmarked yet. The government allegedly also withdrew Rs 44.24 lakh against electrification and water supplies though the basic structure of the High Court building is yet to be completed. The construction started in 2007 with an estimated budget of Rs 43 crore. Eleven years hence, only 35 percent of the work has been completed.

The Gauhati High Court directed the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) to conduct a preliminary investigation into charges of misappropriation of public money in the construction of the complex in Kohima.

Between March 2009 and March 2017, there were 18 withdrawals by the Department of Justice and Law, Nagaland, and the project cost was increased to Rs 52.63 crore. The department also took a loan of nearly Rs 2.46 crore from HUDCO. The Court said: “Therefore, there is a prima facie case of misappropriation of huge public money and siphoning off the same in a systematic manner to the gross prejudice to the public exchequer.”

Though the situation is slightly better in Delhi, tales of misappropriation of funds abound. The recent turmoil in the Tis Hazari courts started as lawyers were protesting against the renovation of the court buildings. A source, on condition of anonymity, told India Legal: “Lawyers themselves are one of the main hindrances to infrastructure development. They are afraid that they might not be allocated a chamber in the new building and they don’t want to lose their old chamber. Hence, they went on strike.” F

In another incident that has become a benchmark of the rusty infrastructure of the judiciary, a former judge of the Allahabad High Court heard a case in the back seat of his car because of unavailability of courtrooms.

The underutilisation of budgets is also a factor in e-courts. The 2018-19 Budget allocated a sum of Rs 480 crore for the E-Court Mission to digitise 709 new courts and provide technical infrastructure to over 6,000 courts. It also entails wi-fi connectivity and providing solar energy in 41 court complexes. But according to data available of 2013-14, out of the total budget estimate of Rs 108 crore which was revised to Rs 77.58 crore, only Rs 38.89 crore has been utilised.

According to those in the know, the digitisation of the Supreme Court and the Delhi High Court are on track. But a different picture prevails in the rest of the country. Audit of Phase I of the mission completed in 2015 found major shortfalls in deployment of technical manpower. The 2016 CAG report on Uttar Pradesh found that out of 468 thin client machine sets supplied in four districts, 208 sets (44 percent), worth Rs 27.87 lakh, were lying idle for more than five years. Supreme Court advocate Eeshan Chaturvedi told India Legal: “I would want more budget. This year’s budget (Rs 1,174.13 crore) must only go into digitising because digitising is a one-time cost.”

According to the 2016-17 Annual Report of the Ministry of Law and Justice, out of Rs 400 lakh estimated for creation of capital assets of the National Judical Academy (NJA), an amount of Rs 88.30 lakh has been released for construction of 20 residential flats for staff of NJA while the release of the second instalment of Rs 88.30 lakh is under process. Chaturvedi said: “The NJA is where judges are trained. Unless you have proper infrastructure budgeting you cannot have the quality of justice dispensation that the country requires. That is why the judiciary needs to invest heavily in NJA.”

While some say the judiciary is at fault, others feel that it should not depend on the executive for the release of funds. Supreme Court Bar Association President Vikas Singh, told India Legal: “The government does not give priority to judiciary. There is such low utilisation of budget mainly because of lack of appointment of judges. There should be a huge infrastructure upgradation so that justice is affordable and quick.” The Policy and Action Plan report of the National Court Management Systems (NCMS) committee formed by the SC states: “If the institution of Judiciary is not independent resource-wise and/or in relation to funds, from the interference of the Executive, judicial independence will become redundant and inconsequential. Executive cannot be allowed to interfere in the administration of Justice by holding back funds for development of judicial infrastructure and expansion of Courts and declining right to appoint sufficient staff, etc.”

A former judge of the Allahabad High Court, Justice AK Tripathi, told India Legal: “Judicial budget is not a planned budget. So they can choose an amount as to what is required. Accor-ding to that it is allocated. It should first of all be a planned budget. Also, the whole process of allocation, release and utilisation gets laid in bureaucracy. Definitely the budget cannot be utilised. If we want to increase the sanctioned strength of the staff, we have to depend on the executive. “

In a December 2017 piece in The Indian Express, SC lawyer Siddhartha Dave wrote: “Politicians often use statistics to criticise the judiciary; they say it is not doing its work properly and should improve its efficiency. But what is conveniently omitted are other statistics: As of April 2017, there were 430 posts of judges and additional judges lying vacant in high courts, and 5,000 posts vacant at the district level and lower. When suggestions to fill vacancies are made by the chief justice, the government’s response is the same: They do not have the money for it. By what miracle does the Executive hope to reduce the pendency of cases without filling vacancies? It probably doesn’t, since that is the only stick it has to beat an independent judiciary with.” Any debate about the reasons why justice is both delayed and denied in India is an endless one. But the double whammy of meagre resource allocation and its underutilisation is something that the country could do without.

Comments are closed.