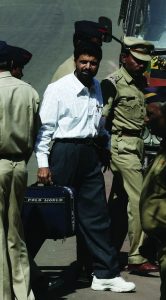

Few chief justices of India have had such a tough tenure—from a series of sensitive and challenging cases to an internal ‘revolt’ by his senior colleagues. Yet, in just over six months, Justice Dipak Misra has put his stamp on the judiciary. An analysis of his legacy

By India Legal Bureau

To be or not to be” was never a dilemma that dogged this legal luminary from Odisha. For Chief Justice Dipak Misra, Shakespeare has been as much a vehicle of expression, as has the language of law. If his literary erudition has shaped his judgments, ample knowledge of legal nooks and crannies has helped him negotiate a treacherous six months as chief justice, with rapid-fire critical cases, an unprecedented ‘mutiny’ by four senior judges and a piquant situation where three three-judge benches overruled one another in similar cases.

His task was unenviable. Few, if any, chief justices have had such a tough stint. Justice Misra also had the unenviable task of first cleaning up the Augean stables that the innards of the apex court had supposedly become. The 42nd Chief Justice of India, HL Dattu, had carried out with him considerable baggage of controversies, being openly close to the BJP and having called for the names of the whistleblowers in the 2G scam case to be revealed. Then, Chief Justice TS Thakur simply could not negotiate the complex Collegium and Memorandum of Procedure issue and broke down in public. That did not add to the prestige of the institution.

Among a myriad cases that Justice Misra has adjudicated as a high court judge, a Supreme Court judge and then as the chief justice, he will be remembered—he retires on Gandhi Jayanti (October 2), a day before he turns 65— for two cases: the Cauvery water dispute and the living will and passive euthanasia cases. It is not just the letter and spirit of law that have been upheld in these judgments, Justice Misra’s approach virtually mirrors English theologian John Wesley’s message that “We should be rigorous in judging ourselves and gracious in judging others.” There has always been that touch of humanity in his pronouncements.

This becomes clear if we consider the passive euthanasia case (see box), in which Justice Misra had to move into people’s very private spaces, spaces they hold sacred and dear and at times wouldn’t share. It had been argued ad infinitum and nobody had been able to come anywhere near a conclusion: how to let a dear one go, or even should one? Even when the pain and suffering were evident, the law stuck to the letter, and the spirit was found wanting in the face of complicated edicts, traditions and emotions. This is a debate that is still confusing judicial systems in the US and Europe. India’s could act as a precedent. Misra cut through the Gordian knot and set free the guilt. It was a difficult task, but it had to be done and needed courage.

Similar was the case with the Cauvery water issue. Rivers and the water in them have been held sacred in India for eons, what with the very plinth of civilisations being built on their banks. The task was to apportion entitlements, but the trick was to decide on each such entitlement. Jurisprudence sometimes runs in the face of pride, and pride always carries bias. Four states were in the basin, and it was left to the judges to decide who deserved more. The judges looked deep into the 2007 Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal formula and realised that the entitlement for the metropolis of Bengaluru was minimal, through an erroneous assumption. The rest was easy.

A long journey

It has been a long journey for Justice Misra (born October 3, 1953). Hailing from Cuttack, the influence of his uncle, Ranganath Misra, the 21st chief justice of India (September 25, 1990 to November 24,1991) was unavoidable. It is not clear if he had any inkling, when he enrolled as an advocate with the Orissa High Court on February 17, 1977, that he was destined to be the third chief justice of India from his state. He had done his law degree from the Madhusudan Law College, Cuttack.

The real journey began when he was appointed additional judge of the court on January 17, 1996. Misra was transferred to the Madhya Pradesh High Court on March 3,1997, where on December 19 that year he became a permanent judge.

He was appointed chief justice of the Patna High Court on December 23, 2009, and was transferred to the Delhi High Court as chief justice on May 24, 2010. On October 10, 2011, he was elevated to the SC with the then president, Pratibha Patil, swearing him in.

On August 28, 2017, he was sworn in as chief justice by President Ram Nath Kovind.

He is known to have deep knowledge of ancient Indian scriptures.

These are the principal cases of his career but probably the toughest time of his tenure at the top was when his role as the Master of the Roster was challenged by no less than the four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court in a virtual ‘mutiny’.

When Justices Jasti Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi, Madan B Lokur and Kurian Joseph held a defiant press conference at the residence of Justice Chelameswar and alleged that Justice Misra was not following precedents and established traditions in allotting cases as per seniority, all hell broke loose.

The media saw the crack in the judiciary as a precursor to the fall of the only neutral edifice of the country at that point and the Executive watched in glee. The common man was left lamenting the death of justice.

Testing times bring out the best in people. Justice Misra started off tough, taking on a massive load, but did not wince at calling the ‘rebel’ judges to meetings in his chamber. The issue settled like a sudden dust storm on the savannah and the office of the chief justice was back where it should always have been.

Looking back, one day, historians might actually realise how disruption can let steam out and iron out age-old kinks in a system. Reacting to the controversy of the revolt, Professor Upendra Baxi, former vice-chancellor of Delhi University, had said at an India Legal conclave: “Crisis is a healthy development, from which better solutions emerge.”

And, as if that wasn’t enough, barely a month after the “mutiny” the court was again rocked, this time over the issue of breach of propriety. Tradition is important at the Supreme Court and is respected. But when, on February 21, a three-judge bench comprising Justices Lokur, Joseph and Deepak Gupta stayed the implementation of a verdict delivered on February 8 by another three-judge bench (comprising Justices Arun Mishra, AK Goel and MM Shantanagoudar), eyebrows went beyond foreheads. It was exacerbated by Justice Lokur’s order of restraining all high courts from entertaining or passing any order on land acquisition matters on the basis of the February 8 verdict.

To add insult to injury, the February 8 verdict was delivered on another land acquisition case which had effectively overturned a judgment delivered by a three-judge bench of Justices RM Lodha (now retired), Lokur and Joseph on January 24, 2014, (this case was about land acquisition in Pune) terming it “per incuriam” (decision rendered without taking care of facts and law).

The main judgments

Chief Justice Dipak Misra has shouldered a heavy load, presiding over a host of sensitive and challenging cases

Passive Euthanasia and Living Will judgment

Judges handling the 42-year trauma of nurse Aruna Shanbaug always stopped short of allowing a medical termination and she stayed that way till she died of a cardiac arrest. While authoring the judgment, Justice Misra came up with a quote from Greek philosopher Epicurus, saying: “Death is nothing to us, since when we are, death has not come, and when death has come, we are not.” While that reflected his conscience, his admitting that the court had been puzzled by the conundrum in “whether the Hippocratic oath should prevent us from entering the dark tunnel of death with dignity,” was self-scrutiny that has been rare of late.

Judges handling the 42-year trauma of nurse Aruna Shanbaug always stopped short of allowing a medical termination and she stayed that way till she died of a cardiac arrest. While authoring the judgment, Justice Misra came up with a quote from Greek philosopher Epicurus, saying: “Death is nothing to us, since when we are, death has not come, and when death has come, we are not.” While that reflected his conscience, his admitting that the court had been puzzled by the conundrum in “whether the Hippocratic oath should prevent us from entering the dark tunnel of death with dignity,” was self-scrutiny that has been rare of late.

Justice Misra could, of course, fall back on the 241st report of the Law Commission, which had said that passive euthanasia should be allowed with safeguards. However, a judgment is the final step in allowing into society a possibility that could change the way we live and, in this case, the way we die.

While many countries across the world have legalised passive euthanasia with safeguards, the delicate religious and social sentiments of a civilisation as old as India needed special understanding and handling.

The “living will” was another humane yet practical touch, allowing the patient to script his or her own death will, so to say. This could surely lead to complications, but that the first step has been taken is the key to a better understanding of ground realities.

Cauvery water dispute judgment

The Cauvery water dispute dates back to the 1890s, hence sentiments associated with it have become lore and tradition. Dealing with people’s very basic needs and instincts have, in the past, resulted in social unrest, even bloodshed. Here, too, the court could fall back on an earlier recommendation, the Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal (CWDT)’s 2007 formula. But tweaking it was critical, because it remained unacceptable to the people. Also, since it involved swathes of land and population in the states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala and Puducherry, and since water was only in finite supply, Bengaluru’s inclusion as a separate demand entity was the masterstroke.

The Cauvery water dispute dates back to the 1890s, hence sentiments associated with it have become lore and tradition. Dealing with people’s very basic needs and instincts have, in the past, resulted in social unrest, even bloodshed. Here, too, the court could fall back on an earlier recommendation, the Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal (CWDT)’s 2007 formula. But tweaking it was critical, because it remained unacceptable to the people. Also, since it involved swathes of land and population in the states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala and Puducherry, and since water was only in finite supply, Bengaluru’s inclusion as a separate demand entity was the masterstroke.

It was a scientific assertion. The court averred that the CWDT had “erred” when it assumed that only a third of Bengaluru fell in the river’s basin and the city should be largely excluded from rights over its water. The other data relied upon was that the CWDT had omitted the 20 TMC (thousand million cubic feet) of groundwater that Tamil Nadu has.

There was no major protest, no upheaval. The bench also made it clear that this formula would last 15 years, after which it will be revisited.

Nirbhaya case judgment

It was a high-profile case, an instance of unbelievable brutality in the gangrape and murder of Jyoti Singh and a case that needed exemplary punishment. Justice Misra concluded the pronouncement of the judgment confirming the death penalty for the four convicts in the 2012 Delhi bus gangrape and murder.

It was a high-profile case, an instance of unbelievable brutality in the gangrape and murder of Jyoti Singh and a case that needed exemplary punishment. Justice Misra concluded the pronouncement of the judgment confirming the death penalty for the four convicts in the 2012 Delhi bus gangrape and murder.

Justice Misra, along with Justices R Banumathi and Ashok Bhushan, read out the part upholding the Delhi High Court’s decision. Justice Banumathi delivered a separate but concurring judgment.

The bench, headed by Justice Misra, agreed with the Delhi Police counsel that anything short of the death penalty would be a “devastation of social trust”. Justice Misra had commented: “If ever a case called for hanging, this was it.”

The Hadiya-Shafin ‘love jihad’ case

On March 8 Justice Misra headed the bench which set aside the contentious Kerala High Court order that annulled the marriage of Hadiya, an adult, with another adult, Shafin Jahan, in what had become famous as the “love jihad” case. Hence Hadiya and Shafin’s marriage was, again, legally valid.

This was a natural outcome. The CJI had always asked the very crucial question: “Can the court interfere with consensual obsession? Can you nullify marriage under 226? I have never come across such a situation. We cannot go into the neurological aspect of consent by an adult of sound mind.”

Yakub Memon judgment

In another unprecedented sitting of a Supreme Court bench, at 3.18 am (verdict being announced at 4.50 am), the three-judge bench of Justices Dipak Misra, PC Pant and Amitava Roy rejected Justice Kurian Joseph’s arguments against a curative petition and held that due process of law had been followed. The bench upheld Mumbai blast accused Yakub Memon’s death order. The court confirmed that Memon would hang, rejecting doubts raised over the legality of the dismissed July 21 curative petition. Simultaneously, the Maharashtra governor also rejected Memon’s mercy petition. His mercy petition with the president was also rejected.

In another unprecedented sitting of a Supreme Court bench, at 3.18 am (verdict being announced at 4.50 am), the three-judge bench of Justices Dipak Misra, PC Pant and Amitava Roy rejected Justice Kurian Joseph’s arguments against a curative petition and held that due process of law had been followed. The bench upheld Mumbai blast accused Yakub Memon’s death order. The court confirmed that Memon would hang, rejecting doubts raised over the legality of the dismissed July 21 curative petition. Simultaneously, the Maharashtra governor also rejected Memon’s mercy petition. His mercy petition with the president was also rejected.

Judgment on FIRs

The Delhi Police had been reined in by Justice Misra when he was with the Delhi High Court in the Own Motion vs State case in which he directed that the police was to upload FIRs on their website within 24 hours of the FIRs being lodged. He did this to enable the accused to file appropriate applications before the court for redressal of their grievances.

WhatsApp privacy case

Justice Misra is also heading a bench hearing a challenge to Delhi High Court’s September 23, 2016 order, allowing messaging app WhatsApp to roll out its new privacy policy, but stopping it from sharing its users’ data collected up to September 25, 2016, with Facebook or any other related company.

The steam has been let out in this as of now, with a five-judge bench in order and the situation contained. At this moment Justice Misra is deep into two more constitution bench hearings, both matters of high importance—the Aadhaar linkage case and the mysterious death of CBI Special Judge BH Loya.

His involvement in these two cases has been especially evident from two comments he has made so far. In the Loya case, he has already given a broad hint by stating: “The question is whether Section 174 CrPC has been duly complied with or not. This could be a ground for suspicion.”

In the Aadhaar case, looking into possible fallouts, he has said: “No penal law can be retrospective but its consequences can be.” In both instances, the comments in the long run could affect the course of the judgment.

Soft-spoken as he is, he has also been prone to showing irritation. When the top court accepted the Jay Shah case (with journalists of the news portal The Wire approaching it), Justice Misra blasted the media, saying: “We respect the freedom of the press, but it has limits. Many in the electronic media think they can write anything. How can they write on anyone whatever they like?” At the same time, showing cautious balance, he has stayed the criminal defamation prosecution in the lower court.

When the mild-mannered, five-feet- four inch man departs the Supreme Court on October 2 after six years, 11 months and 22 days, Justice Dipak Misra will leave behind a legacy for his successors that bears his unmistakeable stamp.

The most significant is the fact that he has defied the sceptics who had, early in his tenure, portrayed him as someone who would blindly follow a pro-Dilli durbar line and become a handmaiden of the executive. He has shown judicial independence on numerous issues, the Aadhaar case being the most recent. Equally, he has displayed a rare and much needed attribute in a CJI—the ability to take tough calls.