Some 10 vaccines are in the human trial phase with more than 100 currently under development. But so far, there is no way to predict which, if any, vaccine will work safely or is even a front-runner

By Kamakshi Singh Mehlwal and Geetanjali Mehlwal

In the Balkans and in central European folklore, a silver bullet is supposed to kill a werewolf (a person who changes for periods of time into a wolf, characteristically when there is a full moon). Vampires are not particularly affected by silver bullets. Traditionally, a silver bullet is something that provides a magical resolution to an enigma or predicament for which a solution does not exist.

The whole world is today looking for a silver bullet to exterminate the novel coronavirus.

As the cases of coronavirus rise exponentially around the world, with the total number of cases soaring as high as 7.09 million with over 406,231 fatalities, the sanguine expectations of positive news about trials and results of Covid-19 vaccines appear to be the only hope for mankind. About 10 vaccines are already in the human trial phase while more than 100 are currently under development, including in India. But so far, there is no way to predict which—if any—vaccine will work safely, or is even a front-runner.

A new antiviral drug from US pharma giant Gilead Sciences called Remdesivir has shown some promise in small efficacy trials and has been approved for compassionate and restricted emergency use by the FDA and Japanese Health Regulators. India’s drug regulator, Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation, has also granted Gilead marketing authorisation for Remdesivir to be used on hospitalised Covid-19 patients.

A glimmer of hope has arisen in the US, where Moderna Inc’s tentative coronavirus vaccine produced protective antibodies in a diminutive group of vigorous volunteers, according to information released by the biotech company on May 21, 2020. Moderna’s Phase I study showed the vaccine was safe and all the eight research participants produced antibodies against the virus. Laboratory analysis initiated in March showed that those who received a 100 microgram (mcg) dose as well as those who received a 25 mcg dose had levels of protective antibodies that exceeded those found in the blood of people who had recovered from Covid-19. This announcement uplifted the shares of Moderna by 20 percent.

The possibility of glitches occurring by the time this vaccine is tested for efficacy in thousands of people is not ruled out. Moderna scientists are trying to figure out what concentration of antibodies will ultimately prove protective against coronavirus and how long that immunity will last. The vaccine appeared to show a “dosage measure response” elicited by more antibodies being produced by participants who were administered 100 mcg dose than those who were given a lesser dose.

US regulators have given the vaccine “fast-track” status to hasten the regulatory re-evaluation permission to start the Phase II stage of human testing with a 50 mcg dose. The US government took a momentous risk backing Moderna’s vaccine with a $483-million grant from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority. The company said that the grant will enable it to supply millions of doses per month in 2020 if the vaccine proves successful. “We are investing to scale up manufacturing so we can maximise the number of doses we can produce to help protect as many people as we can from SARS-CoV-2,” Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel reportedly said, using the official name for the new virus. In May, Moderna signed a 10-year strategic collaboration with Lonza Group that will allow the company to make up to one billion 50 mcg doses by the end of 2021. Moderna said it expects to start a larger Phase III trial in July.

On May 17, Israel’s Institute for Biological Research announced that it has concluded successful coronavirus vaccine experiments on rodents, making provision for further testing on other animals and eventually, human trials. It hopes to have a vaccine ready in less than a year. Outgoing defence minister Naftali Bennett announced that successful isolation of the antibody could be used to develop treatments for Covid-19, and that it was ahead of the world in those efforts.

This development will not be useful in the creation of a vaccine, but will facilitate a drug treatment for those who have already contracted the disease. During the trials, two groups of rodents were infected with the coronavirus, but only one group had first been given the vaccine. While the unvaccinated group became sick, the vaccinated rodents remained healthy. Upon success, this trial will move to humans.

Even though institutions around the world have discovered antibodies capable of destroying the virus, the Israeli laboratory said it was the first to reach three major milestones—finding an antibody that exclusively targets this coronavirus, this antibody is monoclonal and that it lacks supplementary proteins that can cause complications for patients.

Eight antibodies to Covid-19 have been identified and international patents on the technology applied for. The antibodies were produced from blood taken from Covid-19 patients who developed serious symptoms, and then recovered. The lab hopes to combine the antibodies into an effective treatment. If researchers are able to make the medicine, they will seek an international drug company to mass produce it.

Similarly, Russia announced on June 1 that it will start using its first drug approved to treat Covid-19 patients—Avifavir. It hopes that this will mitigate the strain on the health system and hasten a return to normal economic life. With over 477,000 cases at present, Russia has the third highest number of infections in the world after the US and Brazil, but has a relatively low official death toll of 5,971.

Russian hospitals have been permitted to start giving Avifavir to patients from June 11, the head of Russian Direct Investment Fund (sovereign wealth fund), Kirill Dmitriev, disclosed. He said the company behind the drug would manufacture enough to treat around 60,000 people a month. Avifavir, known generically as Favipiravir, was first developed in the late 1990s by a Japanese company which was later bought by Fujifilm. Russian scientists have modified the drug to enhance it, and Moscow said it would share the details of those modifications. Japan has been testing the same drug, known there as Avigan. It has won acclaim from Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and $128 million in government funding has been given for it, but it has yet to be approved for use.

Dmitriev said clinical trials of the drug had been conducted on 330 people and it had been seen that it successfully treated the virus in most cases within four days. He said Russia was able to cut testing time-scales because the Japanese generic drug which Avifavir is based on was first registered in 2014 and had undergone significant testing before Russian specialists modified it. “We believe this is a game-changer. It will reduce the strain on the healthcare system and we’ll have fewer people getting into a critical condition,” Dmitriev reportedly said. “We believe that the drug is key to resuming full economic activity in Russia.”

Meanwhile on May 29, Albert Bourla, CEO of Pfizer, an American pharma company, claimed that “if things go well, and the stars are aligned, we will have enough evidence of safety and efficacy so that we can… have a Covid-19 vaccine around the end of October”. As of June 2, the company is currently in the clinical trial stage developing their vaccine alongside Germany’s BioNTech. The project relies on messenger RNA technology never before used in an approved vaccine. It was administered to humans in Germany in May and there are hopes that a US trial will begin soon, pending regulatory permission.

Currently, Pfizer is conducting clinical trials with German firm BioNTech on several possible vaccines in Europe and the US. Its mission is to make 10-20 million doses of the coronavirus vaccine by the end of 2020 for emergency use should it pass tests. Making millions of doses within just months, as Pfizer hopes, would entail almost unprecedented speed and require swift regulatory action. If the vaccine’s efficacy and safety is demonstrated, Pfizer is looking to increase production speedily to have around 10-20 million doses by the end of this year.

Britain’s AstraZeneca said in May that it had joined with the University of Oxford on a vaccine project also being tested on volunteers. They are also projecting an end-of-the-year release date.

While it takes years to get approvals for the use of vaccines, a Covid-19 vaccine that proves safe in trials can be granted approvals for emergency use. It can take years for a new vaccine to be licensed for general use, but in the face of this pandemic, experimental vaccines shown to be safe and effective against it could definitely win approval. Dr Anthony Fauci, the US government’s top expert, has cautioned that even if everything goes perfectly, developing a vaccine in 12 to 18 months would set a record for speed. The hunt for the game-changer silver bullet or magic potion will hopefully soon be over.

—The writers are advocates in the Supreme Court

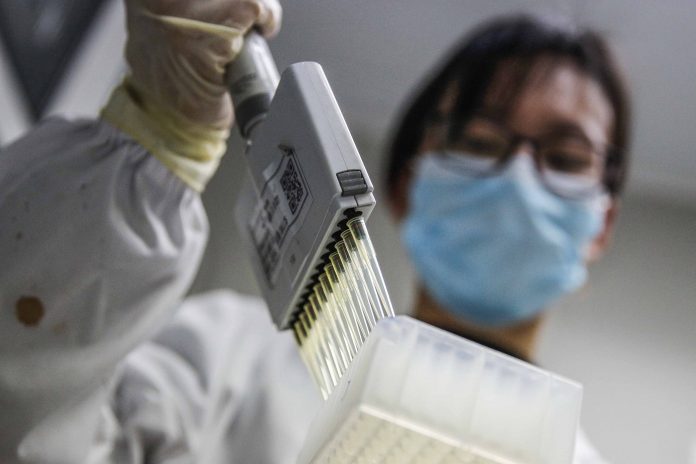

Lead picture: UNI