Maneka Gandhi wants the National Commission for Women to “provide a window” to men who are falsely implicated by women in various crimes. Is this a progressive idea whose time has come?

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

The concerns of men and women have often clashed with each other in custom, law and society. This was brought out recently when Women and Child Development Minister Maneka Gandhi asked the National Commission for Women (NCW) to “provide a window” to men alleging false complaints of dowry torture, domestic violence, sexual harassment and rape. Gandhi wants this window installed in the online complaint system of NCW and made operational within a fortnight. She has cited a reported increase in the number of such complaints.

The matter of women misusing law and lodging false complaints against men and their families has been exercising the legal fraternity and policymakers ever since the Delhi Commission for Women in 2014 published a report claiming that 53 percent of rape cases filed in Delhi are false. Independent research by journalists has also shown that of all the rape cases brought to trial in Delhi in 2013, the largest number (40 percent), pertains to consensual sex criminalised by parents. In such cases, the woman had been coerced to file a complaint. The study finds that the media’s alarm over stranger rape, the kind most reported, is actually over-blown, as this constitutes a miniscule three percent of the cases.

FALSE ALLEGATIONS

A large category of rape cases also pertains to those wherein the man has broken the promise to marry the woman, or simply left the relationship, a decision to which he has a fundamental right under Article 21 of the constitution—the right to freely choose one’s spouse also being part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948. Thus, in 2014, a trial court in Delhi ordered action against two women for filing false rape plaints in separate cases, saying that “women making false rape allegations need to be prosecuted and punished”.

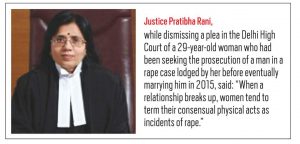

Recently, the Delhi High Court dismissed the plea of a 29-year-old woman, who had been seeking the prosecution of a man in a rape case lodged by her before marrying him in 2015. “When a relationship breaks up, women tend to term their consensual physical acts as incidents of rape,” Justice Pratibha Rani observed, while handing the ruling.

Since the 1980s, men’s rights campaigners such as Supreme Court advocate Ram Prakash Chugh have been fighting for gender-neutral laws and addressing the concerns of men in India, citing an anti-male bias in several Indian laws (see box). Some of their demands include not granting alimony to the wife if she is the primary earner of the family, joint custody of children in case of divorce and inclusion of men in laws related to domestic violence, sexual harassment in the workplace and rape. They resent the automatic assumption by society that women are the victims and men, the predators.

Says Chugh: “I think an opportunity for men to present their side of the story has been long due. The women and child development ministry also has the mandate to protect the female family members of the male victim. Arbitrary application of criminal law to the ordinary wear and tear of married life wrea-ks havoc on a family. A certain amount of affirmative action and positive discrimination with regard to women may be justifiable under some circumstances, but misuse of the law to settle personal scores should not be permitted.”

“SUCCESS OBJECTS”

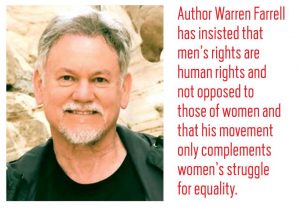

It was Warren Farrell who through his writings in the mid-1990s, including The Myth of Male Power and Why Men Earn More, first espoused the same cause and is, thereby, known as the father of the men’s movement in the West. He rues the fact that just as women are seen as sex objects by society, so too are men seen as “success objects”. It is they who do the most risky, difficult and challenging jobs and must earn a threshold sum of money to prove their social worth. Dissident feminists like Camille Paglia agree with him. Paglia lashed out in November 2016 against the all-pervasive and powerful media culture of what is called by some thinkers as modern-day “grievance feminism” in which women want to take all the risks of freedom but put the onus and responsibility of their own protection solely in the hands of figures of authority like the police and government, whereas men are expected to protect themselves. This is against the principle of equality espoused by classical feminism, she said. True equality is gender neutrality of all laws, says Paglia.

Quite pertinently, a Solapur court in October 2016 ordered a woman to pay maintenance to her younger, homemaker husband citing the Hindu Marriage Act. According to Section 24 of the Hindu Marriage Act, either spouse can claim maintenance even though there is no provision for the husband to do so under the Hindu Marriage and Adoption Act.

As in India, it is men who marry down in terms of income or even other criteria, like age and caste; it results in women claiming maintenance when marriages break down rather than vice-versa.

Gandhi’s move seems a progressive one when seen in this light. However, the NCW, which was set up as a statutory body in January 1992 under the National Commission for Women Act, 1990, and does not fall under the control of the WCD ministry, has said it may be unable to comply with the request. “I can’t take a stand on this just like that. We will have to look into it from the point of view of our mandate. We are answerable to parliament and I can’t just take a decision very lightly, unless we discuss this in detail,” its chairperson Lalitha Kumaramangalam reportedly said. The NCW handles about 23,000 cases annually.

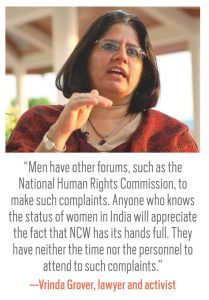

Lawyer and activist Vrinda Grover told India Legal: “It is not the mandate of NCW. Men have other forums, such as the National Human Rights Com-mission, to make such complaints. Anyone who knows the status of women in India will appreciate the fact that NCW has its hands full. They have neither the time nor the personnel to attend to such complaints.”

Lawyer and activist Vrinda Grover told India Legal: “It is not the mandate of NCW. Men have other forums, such as the National Human Rights Com-mission, to make such complaints. Anyone who knows the status of women in India will appreciate the fact that NCW has its hands full. They have neither the time nor the personnel to attend to such complaints.”

Skewed Laws

These are some of the issues raised by men’s rights organisations. Judge for yourself whether they are fair:

- Section 498A IPC pertains to harassment of married women for dowry (automatic arrests until July 2014 when it was stopped by the Supreme Court)

- Section 113b of the Indian Evidence Act, 1879 (husband under scanner if wife commits suicide within seven years of marriage)

- Guardians and Wards Act, 1890 and Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956 (Neither of these laws have any provision for shared parenting or joint custody)

- Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act (in case of unmarried female minor, the husband, even if minor, is her guardian)

- Marriage Laws (Amendment) Bill, 2010 (which lets the wife oppose the dissolution of marriage if husband cannot provide for her)

- Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

- Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 (rape not gender neutral, voyeurism and stalking no longer gender neutral)

- Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013

- Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act (only wife can claim maintenance)

- Section 497 IPC (only men can be prosecuted for adultery)

- No paternity leave

- First rights to women on public transport, in queues and cinemas

- Priority for drop and pickup to women on night shifts

- Equal division of housework and child care advocated but male homemakers looked down upon

- Consensual sex with or without the promise of marriage considered rape

- Government agencies for protection of women and not for that of men

PASSING THE BUCK

Meanwhile, a men’s rights group has decried both Gandhi’s letter and the NCW refusal as “mere passing the buck”. Social activist Kumar Jahgirdar claims he has written to the prime minister demanding the setting up of a national commission for men that can look into cases of false complaints about dowry and sexual harassment at the workplace.

Meanwhile, a men’s rights group has decried both Gandhi’s letter and the NCW refusal as “mere passing the buck”. Social activist Kumar Jahgirdar claims he has written to the prime minister demanding the setting up of a national commission for men that can look into cases of false complaints about dowry and sexual harassment at the workplace.

But his demand, on the face of it, seems reactionary. Even Farrell has insisted that men’s rights are human rights and not opposed to those of women and that his movement only complements women’s struggle for equality. But he, too, has admitted that the ranks of his followers, by default, include some status-quoists and neo-patriarchalists, who are only threatened by the advance of women and want to limit their success.

Considering the statistics showing the poor condition of women in India—skewed sex ratio, female foeticides, school drop-outs and declining participation in the organised labour force—why would anyone seek the setting up of government agencies for affirmative action for men rather than women?

Nonetheless, if Gandhi’s idea smoothens out matters between the sexes, it should be encouraged.