The new consumer protection bill seeking to replace the 1986 Act is grand in design and seeks to rein in online fraud, but has too many contradictions and loopholes to be effective

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

AFTER becoming vice-president, M Venkaiah Naidu came across an ad for a medicine that promised almost magical weight loss. He paid Rs 1,230 up front, expecting the pills to arrive at his doorstep. However, he soon received an email telling him there was another tablet he needed to buy and it would cost another Rs 1,000. Naidu wrote to the consumer affairs ministry which located the peddler in the US. So that bottle of Chanel perfume you gifted your wife on her birthday? It might well turn out to be fake, especially if you ordered it in a “mega e-sale” over the year-end and paid a substantial discount.

FAKE IN INDIA

A recent investigation, the results of which are available in the public domain, has found that more than 60 percent of sports goods being sold online are counterfeit while 40 percent of apparel listed is also by duplicate manufacturers. India is the fifth biggest exporter of fake goods globally, following China, Turkey, Singapore and Thailand, and the automobile parts (grey market percentage at 33.7), personal goods (with a 31.6 percent grey market), computer hardware (27.9 percent) and mobile phones (25.4 percent) are the worst affected markets, data from the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry says. US footwear brand Skechers recently filed a petition against Flipkart and four sellers—Retail Net, Tech Connect, Unichem Logistics and Marco Wagon—in the Delhi High Court for allegedly selling counterfeits. “Flipkart is an online marketplace that helps sellers connect with customers across the country,” a company spokesperson told the media. “We only act as an intermediary.”

“Snapdeal complies with the due diligence requirements as specified per applicable laws. The ‘Terms of Use’ and ‘Report Abuse & Takedown Policy’ for the marketplace are framed and implemented in accordance. Any complaints regarding counterfeit products/IPR infringement are promptly acted upon, including disabling the product and/or the seller from using the platform,” a spokesperson for Snapdeal told India Legal.

It has come to the knowledge of India Legal that most online retailers ask for a letter of authorisation from the brand and invoices from the supplier before admitting their product into the marketplace though they do not conduct a physical check. If a seller is found peddling counterfeit goods, he is blocked, the product delinked from the marketplace and a prompt refund ensured.

It has come to the knowledge of India Legal that most online retailers ask for a letter of authorisation from the brand and invoices from the supplier before admitting their product into the marketplace though they do not conduct a physical check. If a seller is found peddling counterfeit goods, he is blocked, the product delinked from the marketplace and a prompt refund ensured.

“We coordinate with brands on a regular basis to help keep the site clean of counterfeits. Through our ShopClues intellectual property protection programme or SCIPP, we make it conducive to brands and rights owners to reach out to us and to protect their IP. Our robust system under the ShopClues Surety programme also ensures that our merchants sell genuine products. We have a zero tolerance for counterfeit/fake products,” said a ShopClues statement.

Still, with the size of the e-commerce market increasing by leaps and bounds (it grew a whopping 45 percent just from 2016 to 2017), thanks to a young demographic, rising smartphone penetration and relatively stable economic growth, the danger of becoming yet another recipient of fake goods sold online has become very real.

The Consumer Protection Bill, 2018, was introduced in the Lok Sabha on the last day of winter session. It will replace the archaic 1986 Act and, for the first time, has brought the e-commerce giants in its broad ambit. But does it have the exact provisions to deal with this new menace? What are its other clauses? How will they add teeth to the Act?

The Consumer Protection Bill, 2018, was introduced in the Lok Sabha on the last day of winter session. It will replace the archaic 1986 Act and, for the first time, has brought the e-commerce giants in its broad ambit. But does it have the exact provisions to deal with this new menace? What are its other clauses? How will they add teeth to the Act?

FRESH APPROACH

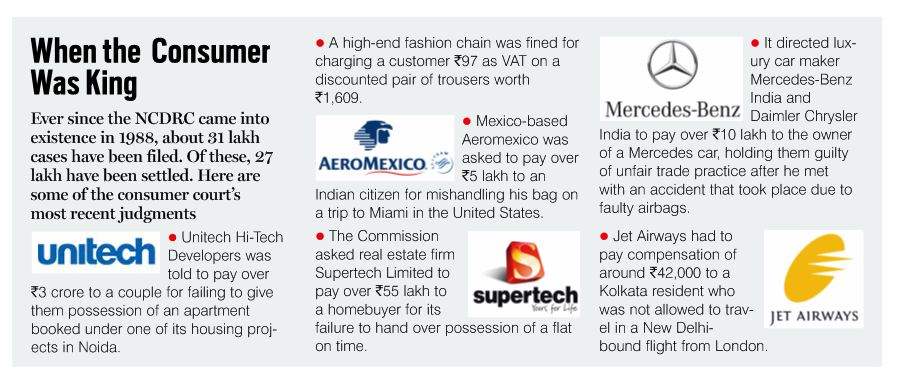

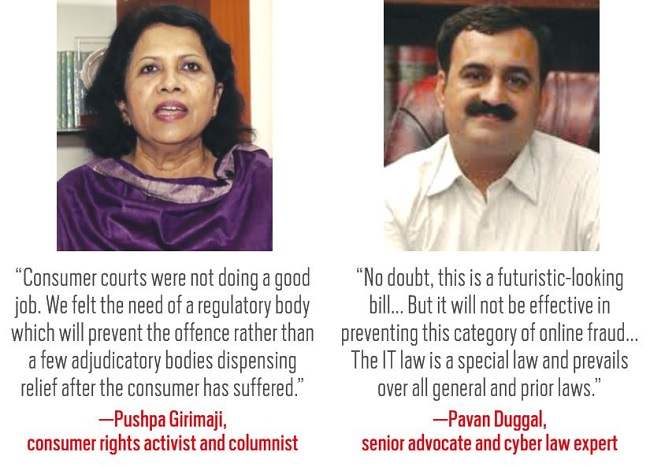

As leading consumer rights activist and syndicated columnist Pushpa Girimaji says, the consumer protection councils and various consumer disputes redressal commissions and forums have not been doing “an adequate job in terms of disciplining the industry and creating a healthy respect for the customer”, as had been envisaged in the 1986 law. The councils have mostly been non-functional while the consumer court does not offer redress to complainants within the stipulated 90 days.

“The manufacturers realise that by filing an appeal, you can go on lengthening the process of adjudication, drag it from the district forum to the state commission and the state commission to the national commission, national commission to the Supreme Court. Then there is the complicated process of jurisprudence. So the consumer courts did not really create fear of the law in the minds of the traders and industrialists. Also, the compensation amount was so meagre that it didn’t really create an impact. Hence we felt the need of a regulatory body which will prevent the offence at the outset rather than a few adjudicatory bodies dispensing relief after the consumer has suffered,” Girimaji tells India Legal.

Along with the then additional, deputy and joint secretaries, department of consumer affairs, the then registrar, National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission, professors Ashok Patil and Suresh Mishra, R Desikan, and George Chariyan, Girimaji was part of the committee that drafted the bill and the one who conceived the Central Consumer Protection Authority, a key reform.

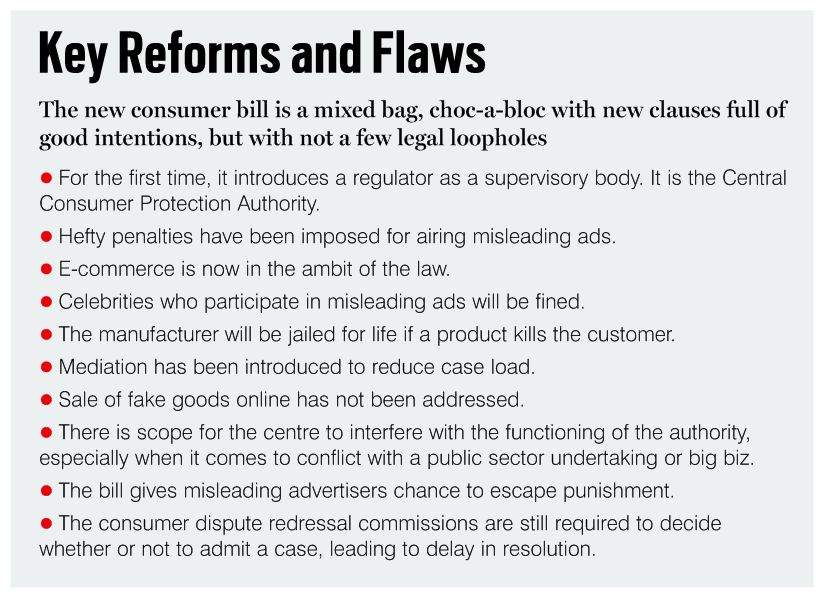

The Central Consumer Protection Authority would be a regulator on the lines of the US Federal Trade Commission, headed by a chief commissioner, with wide-ranging powers to launch inquiries, either suo motu or on a complaint or direction from the government, into violations of consumer rights, initiate prosecution in an appropriate court, recall goods and penalise errant companies, search premises and seize products, and order compensation.

If, after preliminary inquiry, the Central Authority feels that the matter must go to any other regulator like the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India or the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, it may refer the matter to it. On the other hand, anyone aggrieved by any order passed by the Central Authority may file an appeal with the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (NCDRC) within a period of 30 days.

In another welcome move, the bill introduces the much-needed concept of affixing product liability in sections 82 through 87. For instance, in case of personal injury, death or property damage caused to a consumer resulting from product defects, the manufacturer, producer and seller are held liable. Punishment may extend up to life imprisonment in some cases.

In another welcome move, the bill introduces the much-needed concept of affixing product liability in sections 82 through 87. For instance, in case of personal injury, death or property damage caused to a consumer resulting from product defects, the manufacturer, producer and seller are held liable. Punishment may extend up to life imprisonment in some cases.

There are hefty penalties and, in a first, a jail term for food adulteration and misleading advertisements. In the light of more and more celebrity endorsements, celebrities found to endorse such advertisements are liable to pay a hefty fine or endure a ban from subsequent contracts. Misleading advertisers will attract a two-year jail term for a first offence and 10 years thereafter. Food adulterers may get anything between one year and a life term.

In terms of checking online fraud, the bill empowers the centre to make rules for preventing unfair trade practices in online trade. It also brings new forms of trade under the purview of the law, including telemarketing, an area where fraud and trade malpractices as well as misleading ads are rampant, says Girimaji. “They violate the Cable Television Network Regulation Act and Rules, and the Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisements) Act.”

An interesting feature of the bill is provision for a Rs 10,000-50,000 fine to deter frivolous complainants. To reduce case burden on the consumer redress commissions and quicken case disposal, a consumer mediation cell will be set up for each of these bodies.

“The bill has been conceived by the government with an aim to better safeguard the rights of the consumer. It contains several key reforms that will strengthen the law and deter wrongdoers,” says Bhola Singh, BJP parliamentarian and a member of the standing committee which looked at the bill’s first draft.

LEGAL LOOPHOLE

But the legal loophole to be plugged in case of sale of fake goods online is Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, says advocate Pavan Duggal, a cyber law specialist. Whenever there is online fraud, e-retailers have been quick to shrug off responsibility by claiming to be intermediaries, Duggal says.

Under Section 79 of the IT Act, the word intermediary is defined as “any person who on behalf of another person stores or transmits that message or provides any service with respect to that message and includes the telecom service providers, internet service providers, web-hosting service providers, search engines, online-payment sites, online auction sites, online marketplaces and cyber cafes”.

Intermediaries are not liable for any third party information, data, or communication link made available by them if their function is “limited to providing access to a communication system over which information made available by third parties is transmitted or temporarily stored or hosted; the intermediary does not initiate the transmission, select the receiver of the transmission, and select or modify the information contained in the transmission; and the intermediary observes due diligence while discharging his duties under this Act and also observes such other guidelines as the central government may prescribe in this behalf”.

The Supreme Court’s 2015 order repealing Section 66A of the same Act has also proved detrimental as it could have been invoked to punish misleading advertisers online, according to Duggal. But no more, as the new consumer bill has stringent measures to punish them across all platforms.

Unfortunately, the proposed law does not have any provision to counteract Section 79. “No doubt, this is a futuristic looking bill and a quantum leap forward in terms of regulating commerce and industry. But it will not be effective as far as preventing this category of online fraud. Section 100 of the new consumer bill states that ‘the provisions of this Act shall be in addition to and not in derogation of the provisions of any other law for the time being in force’. Section 101 empowers the central government to make rules, a step which could be taken to address this, but the rules cannot take precedence over the IT Act. That’s because the IT Act is a special law. It prevails over the general and prior laws,” Duggal says.

So, in effect, if a consumer is unaware of fraud, and does not request a return within the time period specified in the online seller’s trading policy, he will have no recourse later. This is one flaw in the new consumer bill.

CONTRADICTORY PROVISIONS

There are other flaws. The 2015 version of the bill, which was withdrawn following the standing committee report in 2016, was revised considerably and Girimaji, who is also on the rule-making committee for the bill, says several unwanted clauses have been inserted.

For instance, one issue regarding the bill would be its apparent lack of independence. Section 99 of the bill states, “Without prejudice to the foregoing provisions of this Act, the Central Authority shall in exercise of its functions under this Act be bound by such directions on questions of policy as the central government may give in writing to it from time to time.”

Then, there are some contradictory provisions, such as on the issue of misleading ads. While prescribing heavy penalties for product endorsers who mislead their audience, the bill gives the offender scope to escape these in a subsequent provision by citing “due diligence”. There is no parameter specified for the process of exercising “due diligence”.

The consumer dispute redressal commissions are also still being required to decide whether or not to admit a case, which leads to prolonging disputes.

“The drafting of the bill has not been up to the mark. The bill has to be fine-tuned to remove anomalies so that it can be effective,” Girimaji says.