In the Economic Survey, the centre accepts the need to address backlogs in the judiciary. This and the inability to fill vacancies of judges may shake the confidence of citizens in democracy and the rule of law

~By Venkatasubramanian

In the latest Economic Survey, unveiled on the eve of the presentation of the budget, the centre acknowledged the need to address pendency, delays and backlogs in the appellate and judicial arenas as the next frontier on the ease of doing business. “These are hampering dispute resolution and contract enforcement, discouraging investment, stalling projects, hampering tax collections but also stressing tax payers, and escalating legal costs. Coordinated action between the government and the judiciary—a kind of horizontal Cooperative Separation of Powers to complement vertical Cooperative Federalism between the central and state governments—would address the ‘law’s delay’ and boost economic activity,” the centre suggested.

Short of treating the Judiciary as another wing of the Executive, the centre expressed its concern that delays and pendency of economic cases are high and mounting in the Supreme Court, high courts, economic tribunals and the tax department. This, it said, is taking a severe toll on the economy in terms of stalled projects, mounting legal costs, contested tax revenues and reduced investment.

Delays and pendency, the centre further explained, stem from the increase in the overall workload of the judiciary. This was due to expanding jurisdictions and the use of injunctions and stays. In the case of tax litigation, this stems from the government persisting with litigation despite high rates of failure at every stage of the appellate process.

Therefore, the centre suggested that courts and the government could act together and considerably improve the situation. Clearly, the centre is seeking support for an understanding of the doctrine of separation of powers, which is different from the manner it is traditionally understood. This doctrine does not mean that the institutions of Judiciary, Executive and Legislature are always at loggerheads. But they are not supposed to be in collusion either, as the Constitution envisages the Legislature and the Judiciary to perform the role of watchdogs, even as the Executive has the power and discretion to exercise the responsibilities assigned to it fairly and effectively.

The Economic Survey, it may be noticed, maintains an eloquent silence over the centre’s omissions and commissions for the delays and pendency of cases in courts. For this, sufficient data is available in the public domain.

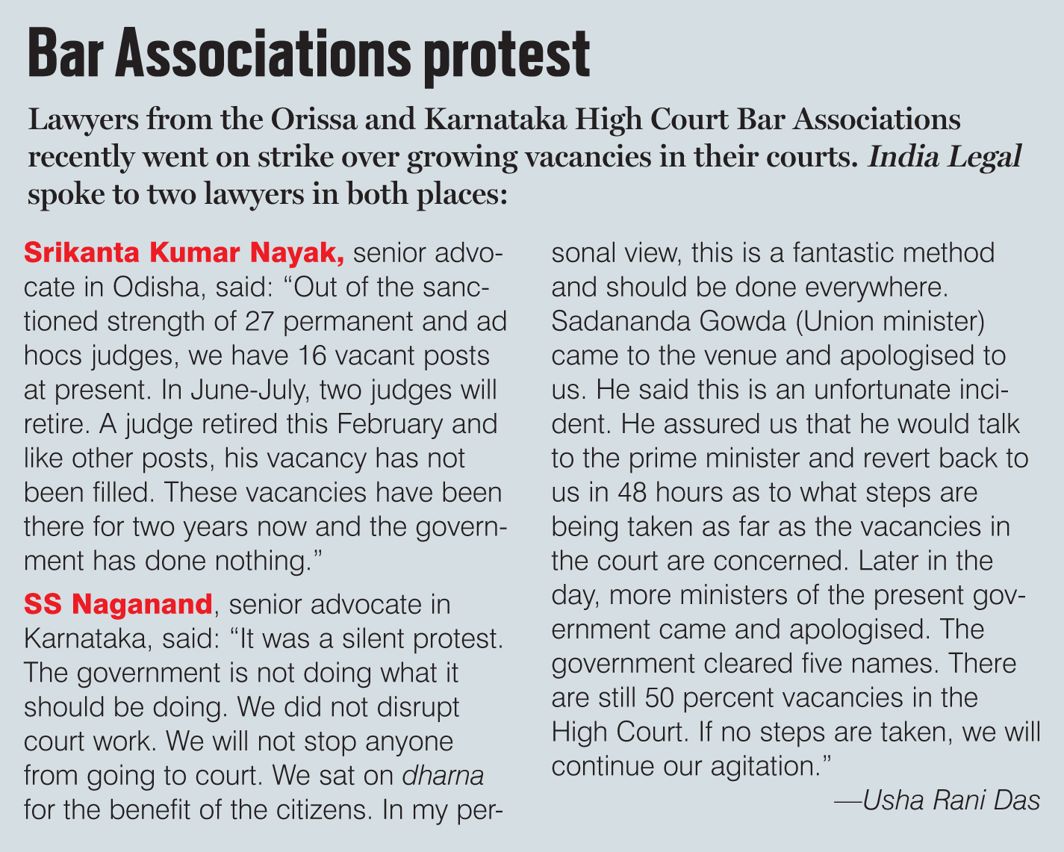

The hiccups in the judiciary have also gripped lawyers and those in the Orissa and Karnataka High Court Bar Associations went on strike recently over the delay in filling judges’ vacancies.

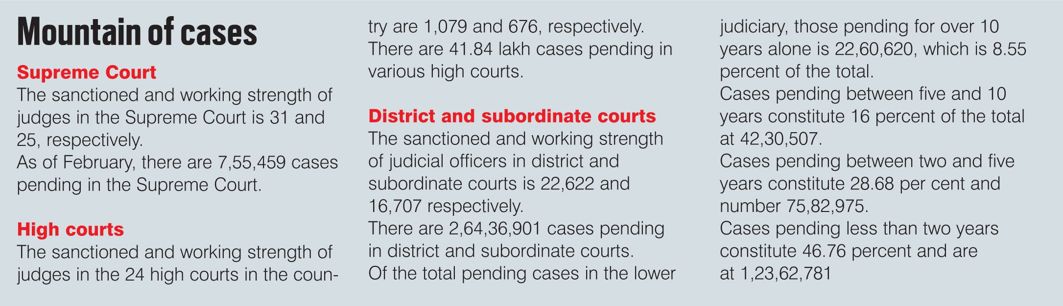

The sanctioned and working strength of judges in the 24 high courts in the country are 1,079 and 676 respectively. The judge-case ratio in district and subordinate courts is calculated to be 1,175 cases per judge.

As per the Constitution, the selection and appointment of judges in subordinate courts is the responsibility of state governments and high courts concerned. The Supreme Court, through a judicial order in the Malik Mazhar case, has devised a process and time-frame to be followed for the filling up of vacancies in the subordinate judiciary. The order of January 2007 stipulates that the process for recruitment of judges in subordinate courts would commence on March 31 of a calendar year and end by October 31 of the same year. The Supreme Court has permitted state governments/high courts variations in the time schedule in case of any difficulty based on the peculiar geographical and climatic conditions in the state or other relevant conditions. The centre does not have a role under the Constitution in the selection and appointment of judicial officers in district/subordinate judiciary.

The sanctioned and working strength of judicial officers in district and subordinate courts is 22,622 and 16,707 respectively. There are a total of 5,915 vacancies in these courts at present. Of the total pending cases in the lower judiciary—2,64,36,901—those pending for over 10 years alone is 22,60,620. This constitutes 8.55 percent of the total. Cases pending between five and 10 years constitute 16 percent of the total and number 42,30,507. Cases pending between two to five years constitute 28.68 per cent and number 75,82,975. Cases pending less than two years constitute 46.76 percent and they number 1,23,62,781.

During a debate in Parliament on January 4 on increasing judges’ salaries, Union Minister for Law and Justice Ravi Shankar Prasad said that the centre favours the All India Judicial Service as an answer to vacancies and pendency of cases, but the high courts are against it. Prasad also said that he was hopeful that he would be able to convince the high courts to agree to the proposal. He said: “The high courts feel it is their domain. If there is Indian Administrative Service, Indian Foreign Service and Indian Police Service, there is a need to have an All India Judicial Service having the best minds of India.” But the centre knows that it is not easy to persuade high courts to cede their domain to the centre.

Even as the centre aims at encroaching on the powers of high courts in order to have a say in filling vacancies in the lower judiciary, the crisis in the higher judiciary is staring in its face. Clearly, the centre cannot absolve itself of its responsibility in not filling the vacancies in the higher judiciary.

The recent stalemate between the centre and the Supreme Court’s collegium in appointing two judges to the apex court is one indication of the extent of trust deficit between the two. The collegium recommended the names of the chief justice of the Uttarakhand High Court, Justice KM Joseph and senior advocate of the Supreme Court Indu Malhotra to be promoted as Supreme Court judges. Both the recommendations were hailed by the community of lawyers and judges as the best nominations in recent times.

Justice Joseph, though not high on the all-India seniority list, is respected for his legal acumen, and therefore, the collegium justified giving preference to merit over seniority. As Justice Joseph is likely to retire as a high court judge at the age of 62 on June 16, 2020, an elevation to the Supreme Court now would help the country utilise his services till he is 65, the current retirement age of Supreme Court judges. But the centre does not favour his elevation because as chief justice of the Uttarakhand High Court in 2016, he had quashed the imposition of President’s Rule in the state when the Congress was in power. Therefore, it is not surprising that the centre is sitting on the recommendation of the collegium, citing his lack of seniority in the all-India list, and the need to balance regional representation in the Supreme Court. If the Centre returns the recommendation to the collegium and the collegium reiterates it, it is binding on the centre. The members of the Collegium, according to reports, are determined to reiterate their recommendation if the centre sends it back for reconsideration.

The reports suggest that the five senior judges of the Supreme Court, who comprise the collegium, are aware that the centre may resist Justice Joseph’s appointment. That is why, it appears, the collegium sent the name of only one high court chief justice for elevation to the Supreme Court. This will allow it to apply sufficient pressure on the centre to act on it, so that other pending names could be recommended later.

There are currently six vacancies in the Supreme Court. The number can go up to 12 as six more judges are likely to retire this year. Due to the stalemate over Justice Joseph, the appointment of Indu Malhotra, who would be the fifth woman judge of the Supreme Court and the first woman member from the Bar to be elevated, is also getting needlessly delayed.

During the debate in Lok Sabha on January 4, Prasad explained the reasons for the delay in finalisation of Memorandum of Procedure (MoP). This has been hanging fire since December 2015 when the Supreme Court directed the centre to submit a revised draft to the collegium in the light of its judgment in the NJAC case. Prasad said: “There are certain issues where we are insisting that there should be greater scrutiny and greater screening so that good people may come…”

On February 7, the Minister of State for Law and Justice and Corporate Affairs, PP Chaudhary, told the Lok Sabha, in response to a question: “The views of the Government were conveyed to the Chief Justice of India on 03.08.2016. The inputs on the MoP of the Supreme Court Collegium was received from CJI through a letter dated 13.03.2017.”

Since then, according to the government’s own admission, there has been no progress towards finalising the MoP. The centre has claimed that it has conveyed the need to make an improvement on the draft MoP to the secretary general of the Supreme Court vide letter dated 11.07.2017. “As the process of finalizing the supplementation of the existing MoP was likely to take some time, at the initiative of the Govern-ment, the matter of continuing the appointment process was taken up with Supreme Court and it is continuing in accordance with the existing MoP to fill the vacancies of Judges in the Supreme Court and the High Courts,” the centre told the Lok Sabha. In January this year, only three fresh appointments of judges in high courts have been made.

The MoS concluded his reply to the Lok Sabha: “The prevailing challenges facing the Judiciary are largely to be addressed by the Judiciary as it is an independent organ under the Indian Constitution. The Government is committed to the independence of Judiciary and does not intervene in its functioning.”

However, there continues to be a huge gap between what the government is professing and what is seen in practice. And the strikes by lawyers of Orissa and Karnataka High Court Bar Associations on the delay in filling judges’ vacancies are an indication that all is cerianly not well in the judiciary.

As on February 2018, 7,55,459 cases were pending in the Supreme Court and 41.84 lakh cases in various high courts. This number is likely to rise exponentially, if the crisis over appointments continues.