Above: Parents and children take out a candlelight march in Delhi in search of safety and answers

There are any number of guidelines and rules but a callous disregard for their implementation has left educational institutions vulnerable in the face of a steady rise in crimes targeting schoolchildren. Will the Ryan killing prove a turning point?

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

Every morning, millions of children set off for schools across the country to fulfill their parents’ dream: To get a quality education. For two sets of parents last week, that dream turned into a nightmare. The back-to-back incidents of sexual violence in two of the National Capital Region’s premier schools, one of them involving the gruesome killing of a seven-year-old boy, woke the nation and the government to a frightening reality: sexual predators and killers are allowed easy access to facilities used by the schoolchildren. While the official machinery creaks into life and fresh guidelines are handed out in panic reaction, it is the parents who are finding it hardest to contend with the new reality facing them following the sodomy bid and murder of the young boy in Ryan International School in Gurugram (see box) and the rape of a five-year-old girl in Tagore Public School, Shahdara, just 24 hours later. The reality is stark and scary: there has been an unprecedented increase in child sexual abuse in recent years and schools have become the new preying ground. In July, a four-year-old girl in Outer Delhi was raped by her school van driver while a three-year-old was groped by another bus driver in Bengaluru the same month. In Chennai, a 13-year-old was accidentally crushed by her own school van driver while her sister sustained injuries.

The brutality of the Ryan International case and the identity of the alleged killer—a bus conductor who was allowed to use the same washroom as the murdered boy—is what has galvanised parents, teachers, educationists and the government, to take serious note of the criminal lack of security in schools. While union ministers Maneka Gandhi and Prakash Javadekar have called an urgent meeting with officials to develop a child safety protocol for schools to follow, the Delhi government has ordered installation of CCTVs and police checks for all non-teaching staff in three weeks time. It may be a case of shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted but the fact that the father of the murdered boy, Varun Thakur, has taken the matter to the Supreme Court is indicative of belated realisation of the importance of child safety and security.

The petition filed by Thakur also seeks a CBI probe into the murder. The fact that the matter is being heard by a bench headed by Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra suggests that the judiciary is alarmed at the lack of security in schools. The petition—a reflection of the panic and anger among parents—asks the courts to “issue a writ in the nature of mandamus directing to various concerned authorities and agencies not only to ensure absolute safety and security of each and every child studying in the schools all across the country but also direct the authorities and agencies to immediately crack [sic] action against all such schools, management, Director, Promoters and Principals for neglecting and ignoring the concern of security and safety of the children… holding the management criminally and vicariously liable and responsible for all any and every act detrimental to the safety and security of the child…”

The petition also listed the rise in child sexual abuse. A sampling of three years data of the National Crime Records Bureau shows 89,423 crimes against children reported in 2014 in sharp contrast to 26,694 such crimes in 2010. That number increased to 94,172 in 2015 and 1,05,785 in 2016. This indicates a four-fold rise in crimes under this category in the last seven years. Also, between 2014 and 2016, the number of crimes registered under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act went up from 8,904 to 35,980—another four-fold increase, this time in just two years. One other horrifying statistic, the only study on child sexual abuse conducted by the ministry of women and child development has found 68.99 percent of those surveyed to be victims. It was completed in 2007 and, significantly, 53 percent of the victims were boys. In fact, there is no comprehensive data on the safety of schools in a particular state or district. Delhi’s child welfare committees report cases that come to them from the Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights (established under the eponymous 2005 Act) and the High Court-appointed Juvenile Justice Committee. These bodies and the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights only maintain records of complaints that reach their doors. Many go unreported because parents do not want to publicise the fact that their child is a victim of sexual abuse. As one member of the child welfare committee in East Delhi’s Dilshad Garden told the media: “The multi-level body set up under the Juvenile Justice Act receives two-three cases of sexual assaults against children within the school premises every month but in most cases, the police say the child has withdrawn it.”

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000 (repealed and replaced in 2015) made it mandatory for a child welfare committee to be set up in each district, with the powers of a first-class judicial magistrate. The committees are tasked with looking into the care, protection, development and rehabilitation of children. It does not seem to have made much difference. The Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights (DCPCR) four years ago had suggested a set of comprehensive guidelines for prevention of child abuse in schools and other educational institutions. However, their half-hearted implementation by the Delhi government has rendered them toothless. The lack of implementation is visible in the lack of knowledge among schools of what is expected of them as per the guidelines. For instance, a child protection policy prominently displayed on the school premises is a must for every institution. Of four leading schools located less than a kilometre’s distance of one another in the posh GK-II area of south Delhi, only one, Don Bosco School, could assure India Legal of having such a policy. The others—Kalka Public School, St George’s School and New Green Field School—were found to be unaware of either the existence of the policy or its contents. All these schools are located in a primarily residential neighbourhood, assuring a degree of automatic community vigilance. What of schools located in remote areas, like the high-profile Amity International School adjacent to the Greater Noida Expressway? Even Ryan International, a school which is part of a sprawling educational empire run by the Pinto family, with 185 schools, including branches in the US, UAE, Thailand and Maldives, seemed to consider safety and security a low priority area. The school is located next to a village and had a breach in the boundary wall, a broken toilet window, outsider access to the school washrooms and mostly non-functional CCTV cameras.

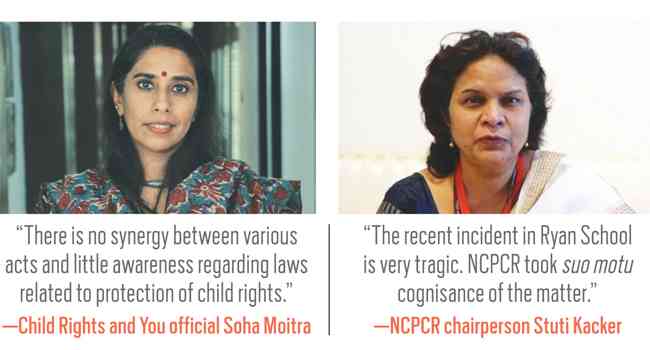

Lack of priority is one aspect, non-implementation of guidelines and lack of any audit mechanism is equally shameful. There is, in fact, no dearth of safety guidelines. As NCPCR chairperson Stuti Kacker points out, there are a total of 24 sets of guidelines on child safety, issued by various bodies such as the ministry of human resource development, the CBSE, the department of drinking water and sanitation, the ministry of road transport, even one on safety in the event of terrorist attacks from the home ministry (see box). However, as education is on the concurrent list, all implementation lies in the hands of respective state governments. “The recent incident in Ryan School is very tragic and urgent. NCPCR took suo motu cognisance of the incident,” said Kacker. In Delhi, the Directorate of Education (DoE) is the agency in charge of monitoring school safety. “We issue our own circulars containing guidelines on specific topics, such as fire safety or transport, from time to time. Inspections are also done fairly regularly, mostly once a year,” Vikas Kalra, a senior official in charge of school education, said. But the checks obviously have not been enough.

So who is responsible? According to the Department of Education, principals and school boards are liable in case of incidents resulting in harm to children. It is their job to ensure that every school has a well-defined child protection policy which includes the following:

- No candidate with a criminal record is recruited for any position within the institution

- Counseling service is made available to every child in need

- A management committee is present to look into every case of child abuse

- Students are put through training modules on gender and sexuality

- At least one female guard is present on the school bus which waits until the child’s guardian arrives to pick them up

- Washrooms are separate for boys and girls as well as for staff and students

- There are no dead-end hallways and staircases

- CCTV cameras are installed and maintained at appropriate places

- No unregistered visitor enters the premises

- Teachers and staff are required to follow a behavior protocol while interacting with students

- Buses must be painted yellow, have the words, school bus, prominently written in front of them, install horizontal grills on the windows, be equipped with a global positioning system and speed governors set at 40 kmph, and be driven by operators who have all their papers in place plus a public service vehicle badge issued by the state transport department. They should have had five years experience driving a regular bus and passed 12th grade (10th for Delhi Transport Corporation drivers). A conductor, too, needs to have passed the 10th standard exam. Anyone who has been ticketed even once for speeding, drunk or dangerous driving may not be recruited for these jobs. Vehicles in a state of disrepair should be kept away from school campuses.

Most of these guidelines are ignored or implemented half-heartedly. One obvious drawback is that many parents hire private vehicles to ferry kids to school. Fiona Manuel is a mother of two—a third-grader and a kindergarten student at Delhi’s Don Bosco school. She is wary of using school vans. “Don Bosco has plenty of school buses. But parents usually go for private vans because they want the child to be dropped at their doorstep. With buses, one has to be present at the drop-off point to collect the child, which is not always possible,” says Manuel. In any event, most schools do not have an adequate number of school buses, forcing parents to depend on private vehicles even though their drivers have unverified antecedents and complaints of sexual offences on their charges has been on the rise. Last week, the Delhi government issued instructions to make schools liable for vans. They will be made responsible for monitoring if vans ferrying their students are following norms. The School Cab Policy 2007 which said the carrying capacity of the vans should be one-and-a-half times the seating space would no longer be applicable. Students would not be allowed to sit on CNG cylinders converted into seating space, as happens with in many cases. Drivers are required to display the public service badge on their new grey uniforms and undergo police verification. For this, they would have to register their vehicles with the transport department. Installation of speed governors and adhering to a limit of 40 kmph would now be a must.

Most of these guidelines are ignored or implemented half-heartedly. One obvious drawback is that many parents hire private vehicles to ferry kids to school. Fiona Manuel is a mother of two—a third-grader and a kindergarten student at Delhi’s Don Bosco school. She is wary of using school vans. “Don Bosco has plenty of school buses. But parents usually go for private vans because they want the child to be dropped at their doorstep. With buses, one has to be present at the drop-off point to collect the child, which is not always possible,” says Manuel. In any event, most schools do not have an adequate number of school buses, forcing parents to depend on private vehicles even though their drivers have unverified antecedents and complaints of sexual offences on their charges has been on the rise. Last week, the Delhi government issued instructions to make schools liable for vans. They will be made responsible for monitoring if vans ferrying their students are following norms. The School Cab Policy 2007 which said the carrying capacity of the vans should be one-and-a-half times the seating space would no longer be applicable. Students would not be allowed to sit on CNG cylinders converted into seating space, as happens with in many cases. Drivers are required to display the public service badge on their new grey uniforms and undergo police verification. For this, they would have to register their vehicles with the transport department. Installation of speed governors and adhering to a limit of 40 kmph would now be a must.

The Ryan Murder: Anatomy of an Investigation

- School bus conductor Ashok Kumar allegedly slashed 7-year-old Pradhyumn Thakur in the neck when he raised an alarm after he attempted to sodomise him in the school toilet on September 8

- Pradhyumn could not scream as his windpipe was severed. CCTV cameras caught him crawling into the school corridor. Police say school authorities later tried to delete the footage

- The post mortem report says Pradhyumn died within two minutes of the attack. School authorities, however, got him transferred to three hospitals. The doctor at the third hospital declared him dead on arrival

- Ashok Kumar allegedly confessed within minutes of questioning by the police the same day. His colleague, school bus driver Saurabh Raghav, has, however, claimed that he is a scapegoat

- The SIT team has detained gardener Harpal Singh for questioning. It has already questioned 17 persons

- Francis Thomas, legal head and Jeyus Thomas, HR head of the Ryan International School group, have been arrested for tampering with evidence. The school has been closed indefinitely

- Ryan management has moved the Supreme Court, seeking transfer of case to a Delhi court for “fair probe”. The court has issued notices to the centre and the Haryana government

- Father Varun Thakur has petitioned for a CBI probe into his son’s murder and safety guidelines for children in schools

- The Bombay High Court declined anticipatory bail to the Ryan International Group’s founding chairman Augustine Pinto (73) and his wife, managing director Grace Pinto (62) and son Ryan Pinto, the CEO of the group, but extended interim relief from arrest to trustees

- The Supreme Court has also agreed to hear a plea of two women lawyers seeking framing of “non-negotiable” child safety conditions and implementation of existing guidelines

There is another key issue to do with growing privatisation and commercialisation of education which has also been cited in the petition filed by the father of the Ryan victim in the Bombay High Court opposing the anticipatory bail petition of the CEO, Ryan Pinto, and his parents, Grace and Augustine Pinto. Many hold this to be the main cause for the growing atmosphere of insecurity in schools and a corresponding rise in crime. For instance, in earlier days, non-teaching staff were permanent and employees of the school. Not anymore, with most of that work being outsourced. This is due to the mushrooming “global” and “international” label that schools freely flaunt and rapid expansion of branches once a school is established.

In the absence of collated data and with low reporting of such incidents, there is little understanding of how insecure children can be even on school premises. The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights is conducting its first survey on safety and security of schools. The audit involves 70,000 public and private schools across the country. The surveys are being conducted by students and teachers and cover infrastructure, prevention of sexual abuse and social discrimination. What makes it difficult to keep tabs on whether a school is complying with safety norms is that different state departments are responsible for enforcing different Acts and guidelines. For instance, the education department can take action against a school under the school recognition norms, but the Juvenile Justice and Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Acts are for the Department of Women and Child Development to enforce. The education department most often merely checks if the school has all the necessary certificates (regarding fire safety, building regulations and the like) issued by other government agencies, but cannot verify all of these through independent inspections. These are mainly meant for government schools and there is even less scrutiny in private schools.

There is also no synergy between the Acts and little awareness, as most of the laws dealing with child rights are comparatively recent. Soha Moitra, regional director of NGO Child Rights and You, says cases that come under the POCSO Act continue to be registered under IPC in many places just because of this reason. “The pace of change in terms of framing of laws has been slow, but the society around us is changing very rapidly. With the decline of the joint family, there is no safeguard for the child. We really need to act urgently and simultaneously,” she said. She also recommends strengthening of the Integrated Child Protection Scheme.

Too Many Guidelines?

Here is a list of various guidelines issued on the subject of safety of children by various government bodies

- Guidelines on Safety and Security of Children, 2014: MHRD

- Guidelines on Food Safety and Hygiene for School level Kitchens under Mid Day Meal Scheme, 2015: MHRD

- Guidelines on Safety of School Buses: Ministry of Road Transport & Highways

- Standard Operating Procedure for Dealing with any Terrorist Attack on Schools: MHA

- lnstructions on Bullying Prevention and Ragging in Schools: MHRD

- Standards of Safety and Precautionary Methods: CISCE

- Activity Book on Disaster Management for School Students: National Institute for Disaster Management

- Operational Guidelines, Child Health Screening and Early Intervention Services under National Rural Health Mission: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare

- CBSE Circular on Modification of its Affiliation By-Laws to include Transport Precautions

- Guidelines issued by Navodaya Vidyalaya Scheme on Prevention of Sexual abuse

- SSA Framework for Implementation 2009 (Chapter 6) on School Infrastructure and Development

- A Handbook for Administrators, Education Officers, Emergency Officials, School Principals/Teachers: MHA

- Guidelines for Swachh Bharat Mission: Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation

- Guidelines for Menstrual Hygiene of Girls: Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation

- Food Safety and Standards Authority of India Guidelines on Banning High Fat, Sugar and Salt in Schools

- CBSE Guidelines for Banning Junk Food in Schools

- Guidelines for Safety of Children in Schools: Department of Education, Government of Haryana

- Safety Guidelines for Protection of Children in Sports by NCPCR with National Institute of Mental Health And Neuro-Sciences and Sports Authority of India

- Safe School Vahan Scheme: Government of Punjab

- Guidelines Issued by Department of School Education, Punjab, to Ensure Safety and Security of Children in Schools, 2016

- NCPCR Regulatory Guidelines for Private Play Schools for Children in the Age Group of 3-6 Years

- Draft Regulatory Guidelines for Hostels of Residential Educational Institution for Children in the Age Group of 7-18 Years.

- NCPCR Recommendations for Inclusion of Safety and Security of Children in Schools Submitted to MHRD on New Education Policy

- Draft Guidelines Being Prepared by NCPCR for Regulating Hostels of Educational Institutions for Children below 18 Years

The Right to Education (RTE) Act prescribes recognition norms for schools. However, by way of safety, the only conditions schools are required to follow is “arrangements for securing the school building by boundary wall or fencing” and providing separate toilets for girls and boys. It is another matter that there are likely to be a large number of schools which don’t meet even these basic standards. The RTE Rules in each state may include further conditions, but most states don’t have specific measures relating to child safety. For instance, the Haryana RTE Rules which are applicable to Ryan International, enable the state government to require schools to furnish compliance reports, but does not elaborate on the nature of compliance. States have their own education Acts which impose additional conditions on schools, but these are likely to be in the nature of furnishing building and fire safety certificates at the time of applying for recognition. The trouble with all these policies is that there is no legal obligation for schools to abide by them. It is little wonder that when seven-year-old Pradhyumn walked into the school washroom, he probably gave little attention to the bus conductor waiting inside with sex on his twisted mind and a knife in his hand.