As protests rage over the release of Padmavati, the Supreme Court has declined to intervene, leaving it to the Censor Board to take a decision. There are numerous other instances when courts have refused to curb freedom of speech and expression

~By Venkatasubramanian

As the release of Padmavati draws near, vociferous protests from state governments and fringe elements have been the order of the day. This is not a new phenomenon. But what needs to be hailed is that increasingly, courts are refusing to stop a film’s release simply because it hurts the sentiments of a particular community.

Going simply by precedent, there are valid grounds why the Supreme Court may consider permitting the release of this film, too. It told two public interest petitioners who sought its intervention last week to stop the film’s release that their pleas were premature as the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), a statutory body, is yet to decide its certification.

The film producers, who expected the Board to certify, had first set December 1 as the date of its release. They, however, deferred it “voluntarily” in view of the protests and threats from a section of the Rajput community who alleged that the film defames the Rajput queen, Padmini. The film is based on fiction authored by 16th century Sufi poet Malik Muhammed Jayasi. The protesters claim that the film shows her consorting with the invader Alauddin Khilji.

The Cinematograph Act, 1952, lays down that a film shall not be certified if any part of it is against the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or involves defamation or contempt of court or is likely to incite commission of any offence.

Under Section 5B(2) of the Act, the centre has issued certain guidelines. A film, these guidelines say, is judged in its entirety from the point of view of its overall impact and is examined in the light of the period depicted in the film and the contemporary standards of the country and the people to whom the film relates, provided that the film does not deprave the morality of the audience. Seen in the light of these guidelines, the protesters have clearly jumped the gun without waiting for the CBFC to complete its review of the film.

The petitioner, Siddharajsinh Mahavirsinh Chudasama and 11 others—all from Gujarat—had submitted to the Supreme Court that Rani Padmavati, a medieval-era queen of Chittorgarh, is worshipped by Rajputs as Sati Rani Padmavati in numerous temples of Rajasthan. The most prominent temple is situated inside the palace of Chittorgarh where thousands of Hindus pay obeisance.

Chudasama and others asked the Court to consider whether in the garb of artistic liberty, historical facts, especially with reference to historical legends, can be distorted so as to cater to the prurient sense of a certain section of the audience. They alleged that the film shows Padmavati doing a “Ghoomar” dance, which is contrary to how this dance is traditionally performed. “The Queens never used to do Ghoomar themselves and the thumkas (hip movement) and the revelation of skin by Padukone, in her portrayal of Padmavati, has hurt the sentiments of the Rajput community,” the petition said. They further alleged that the film has love scenes between Padmavati and Alauddin Khilji, who was the second and the most powerful ruler of the Khilji dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate and who marched to Chittorgarh to have a glimpse of her. Legend has it that Padmavati and other women of Chittorgarh committed sati before Khilji and his forces entered the fort in order to avoid being victims of their lust after their menfolk, led by the king, lost the battle.

The petitioners contended that the violent protests against the film’s release are indicative of the grievances of members of the Hindu community, which also need effective redressal. “Though the script is not in public domain, but once the movie is released and if there is anything which is against the traditional portrayal of Rani Padmavati, then irreparable loss would be caused and the same might even escalate to a law and order problem,” the petitioners cautioned the Supreme Court. They, therefore, sought the Court’s directions to constitute a committee of eminent historians and prominent citizens to prescreen the movie for them, so that they could check the veracity of the script.

Thus, without seeing the movie or verifying its contents, the petitioners alleged that in the garb of creativity, the producers of the film had taken undue liberty and completely changed historical facts. “It is submitted that the portrayal of historical legends have to be done in a historically accurate manner and creativity cannot be used as a pretext to malign or sully their image,” they contended.

However, the Supreme Court bench of Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justices AM Khanwilkar and DY Chandrachud dismissed the petition on November 10, on the ground that the Censor Board was yet to take its decision in “an independent manner”.

On November 20, the same bench had to deal with a similar petition, this time filed by an advocate, Manohar Lal Sharma, against Padmavati. The bench reiterated its view that its interference would be tantamount to pre-judging the matter, as the film has not yet received a certificate from the CBFC. The bench, however, thought it apt to strike off what Sharma had stated in paragraph 17 to 22 in entirety and made it clear that what was struck off should not be used otherwise. “Pleadings in a court are not meant to create any kind of disharmony in the society which believes in the conceptual unity among diversity,” the bench held.

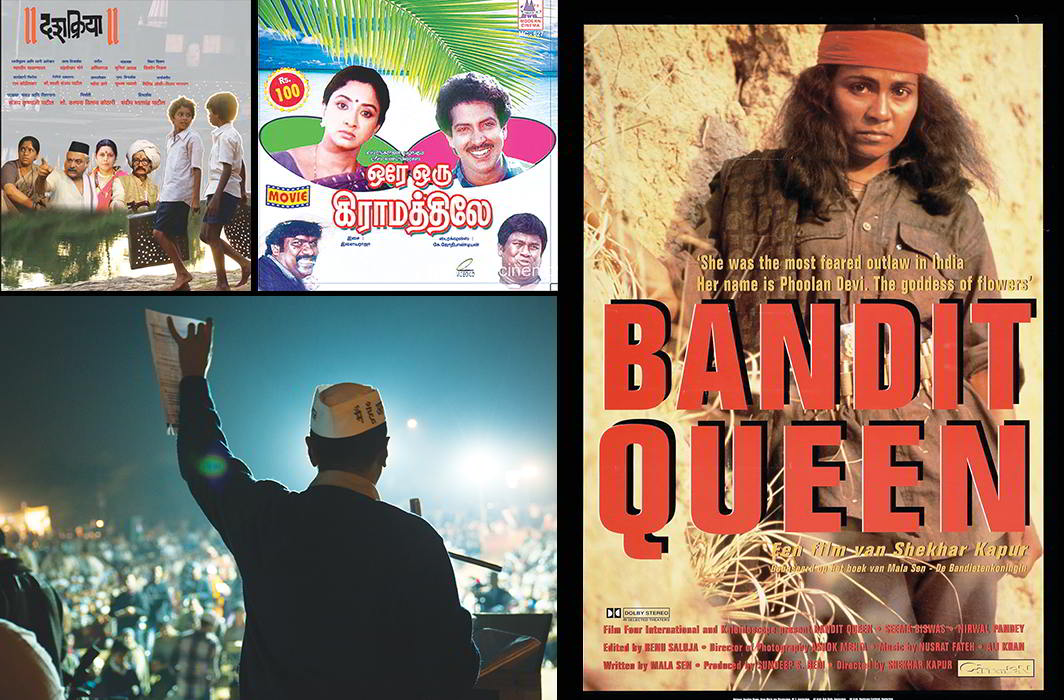

The bench told Sharma that from Bandit Queen to An Insignificant Man, the Supreme Court has always rejected pleas for bans on movies. Although the bench did not go into the merits of Sharma’s plea that even the promos of a film cannot be released without the film’s certification, the bench found that it was not competent to intervene when a statutory body was about to exercise its duty in the matter.

The bench told Sharma that the Court’s decision in Nachiketa Walhekar v CBFC, rendered on November 16, was instructive. In this case, Walhekar’s petition seeking a stay on the nation-wide release of the film, An Insignificant Man, was heard by the bench on November 17. The documentary, which shows the early days of the Aam Aadmi Party, which is in power in Delhi, was sought to be stayed because it contains a video clip pertaining to the petitioner. Walhekar, an accused in a case, allegedly threw ink on Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal. Walhekar claimed that the video clip was originally shown by the media, but after a complaint was filed at Patiala House Courts, it was not shown and therefore the film, too, should not have been granted a certificate by the CBFC.

The bench held that freedom of speech and expression are sacrosanct and it should not be ordinarily interfered with. The bench made it clear that it would restrain itself in not entertaining the writ petition or granting an injunction against the movie’s release on November 17 when the CBFC had already granted it the certificate.

The bench held: “A film, or a drama or a novel or a book is a creation of art. An artist has his own freedom to express himself in a manner which is not prohibited in law and such prohibitions are not read by implication to crucify the rights of an expressive mind.”

It added: “A thought-provoking film should never mean that it has to be didactic or in any way puritanical. It can be expressive and provoking the conscious or the sub-conscious thoughts of the viewer. If there has to be any limitation, that has to be as per the prescription in law.”

Dismissing Walhekar’s petition, it held: “The courts are to be extremely slow to pass any kind of restraint order in such a situation and should allow the respect that a creative man enjoys in writing a drama, a play, a playlet, a book on philosophy, or any kind of thought that is expressed on the celluloid or theatre, etc.”

The Bombay High Court, too, has faced a similar petition, this time against the release of the film, Dashkriya, which means posthumous rites and rituals. The petition was filed based on the official trailer of the film and was dismissed by the Court.

The petition, filed by one Sameer Shankarrao Shukla and others, alleged that the screenplay of the film offends the sentiments of the Brahmin and barber communities. The filmmakers, it said, have no right to introduce something in the film which is not present in the novel on which it is allegedly based. Thus, it said, the film is a distorted version of the novel. The novel is not a historical document, but an imaginative story for which it cannot be rendered the status of gospel, the petitioners further contended.

The film is based on Baba Bhand’s novel, Dashkriya, published in 1994, and its theme is against the commercialisation of such rites. Justices Mangesh S Patil and SS Shinde of the Aurangabad bench of the High Court, in their judgment delivered on November 17, refused to intervene as the CBFC had already given its certificate for the film.

Fanfiction and plagiarism

In copyright law, a derivative work is a creation that includes major copyright-protected elements of an original, previously created first work. Derivative work may be scholarly or interpretive as in biographies and essays or imaginative as in historical fiction, mythological fiction and fanfiction.

The relatively new fanfiction genre is a genre of fiction, more specifically derivative fiction, wherein a fan of a particular book, film, television show or historical or mythological story writes missing scenes, back stories, prequels and sequels of their favourite stories, or simply places their favourite characters in an alternative universe and creates a different storyline altogether. By definition, fanfiction is of variable quality. Fanfiction began as an underground activity in the west during the 1960s via the Star Trek fandom, but has been legitimised ever since through various laws and litigation. A famous example of contemporary fanfiction is EL James’ Fifty Shades of Gray. The writer Jane Austen’s works, too, have been fanfictionalised. At present, there are a whopping 900 such spin-offs in published form. Pride and Prejudice accounts for the majority of published Austen-inspired books.

In India, the tradition of writing historical fiction is very old. Some of the most famous writers include KM Munshi in Gujarati literature and Saradindu Bandopadhyay in Bengali. The phenomenon of fanfiction is again, however, more modern. Notable recent works include Amish Tripathi’s Shiva trilogy and television serial Shree Krishna, both of which are wildly imaginative, uncontroversial fanfiction using the gods as characters.

The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, an international copyright treaty, stipulates that derivative works shall be protected although it does not use this term. An extensive definition of “derivative works” is, however, given by the United States Copyright Act. Under it, all creative works are protected by the fair use doctrine.

Not surprisingly, the legitimisation of fanfiction as a literary genre has come about only after a few run-ins with the law. And some works have either been killed or edited first and then put into the public domain. As Darren Hudson Hicks writes in The Aesthetics and Ethics of Copying, fanfiction continues to pose a confounding legal and business dilemma. Here are a few of the more famous lawsuits.

The Sherlock lawsuit: After creating a critically-acclaimed annotated version of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, author and editor Leslie Klinger wanted to produce an anthology of new Holmes stories written by modern authors. But in 2013, Klinger received a letter from Conan Doyle Estate Ltd demanding that he pay copyright licensing fees if he wanted to release the book. Klinger sued, and in June 2014, US Circuit Judge Richard Posner agreed, saying he could not find “any basis in statute or case law for extending a copyright beyond its expiration”. He even called the estate’s demands for licensing fees on the expired works from authors like Klinger a “disreputable business practice” and “a form of extortion.” The judge awarded Klinger the attorneys’ fees he spent fighting the case. The estate later appealed to the US Supreme Court, but the justices dismissed the appeal in November 2014.

The Harry Potter Lexicon: The Harry Potter Lexicon was launched in 2000 as a comprehensive online encyclopaedia for JK Rowling’s massively popular fictional universe. It was started by a school librarian and Potter fan named Steve Vander Ark. Rowling initially praised it. But when a Michigan book publisher called RDR Books announced plans to turn the Lexicon into a published book and sell it for profit, Warner Bros. and Rowling filed a suit in October 2007, claiming the planned book infringed on their copyrights. However, in 2009, RDR was given the green light to release a truncated version that included less of Rowling’s creative content.

Axanar: In January 2017, just weeks after a US district court judge rejected the claims of fair use from the producers of the Star Trek fan film Axanar, Paramount Pictures, producers of the original series, and Axanar Productions announced a settlement by which “substantial changes will be made to Axanar to resolve this litigation” and future productions from the company will adhere to the new fan film guidelines put forth by Paramount as a result of this case. Axanar is a prequel of Star Trek.

60 Years Later: The reclusive author of the iconic Catcher in the Rye, JD Salinger, has not published any work in nearly half-a-century. However, when Salinger became aware of a planned novel , 60 Years Later: Coming Through the Rye, by one Fredrik Colting, a story that followed a 90-year-old fictionalised Salinger attempting to “kill” a 76-year-old version of Holden Caulfield, Catcher’s angsty teen protagonist, in 2009, he filed a court case. It led to US district judge Deborah A Batts issuing a preliminary injunction blocking the publication of the book. The ruling was later overturned by the Second Circuit Court for “lack of proof of irreparable harm”, but the two sides eventually agreed to a permanent injunction barring the book from ever being published in the United States.

Thus it is seen that, while the conceptual distinctions between various genres of creative work are unambiguous, a piece must have enough original material to merit release or publication.

—Compiled by Sucheta Dasgupta

The bench concluded that the contention of the counsel appearing for the petitioners that what is conveyed in the film is not traceable in the book was the subject matter in the exclusive domain of the CBFC when permission was granted to release the film. Besides, the question of violation of one’s right to practise religion does not arise as there is no ban on the performance of such rituals, the bench reasoned. The High Court relied on the Supreme Court’s recent order in the Nachiketa Walhekar case to further buttress its decision.

Thus, in recent times, the judiciary has avoided interference with the artistic freedom of a filmmaker, citing the responsibilities of the CBFC in permitting or refusing such permission to release a film. The judiciary also appears to be of the view that once the CBFC takes a decision on certification, there is no scope for the judiciary to step in and review the decision as, unlike the CBFC, it is not competent to decide on the merits of certification.

In S Rangarajan v Jagjivan Ram, the Supreme Court held that its commitment to freedom of expression demands that it cannot be suppressed unless the situations created by allowing the freedom are pressing and the community’s interest is endangered. In Rangarajan, it was argued that certain groups in Tamil Nadu had threatened violence if the film, Ore Oru Gramathile, went ahead—a classic case of the heckler’s veto. Rejecting it, the Court asked what good is freedom of expression if the State does not take care to protect it. Freedom of expression cannot be suppressed on account of threat of demonstration and processions or threats of violence… that would be tantamount to negation of the rule of law and a surrender to blackmail and intimidation, it said. The Court’s answer, thus, was to require the State to maintain law and order, and ensure that there is a safe space for freedom of expression without concomitant violence.

In D-G, Doordarshan v Anand Patwardhan, the latter’s film, Father, Son and Holy War, about sexual violence and communalism in India, was given an A certificate. Doordarshan refused to telecast it. It was argued that the film, if telecast on Doordarshan, would be viewed by illiterate and average persons who would be affected by its screening. The Supreme Court rejected this argument saying that the standard must be that of a “reasonable person” with an “average, healthy and common sense point of view”. The Court found that, as a matter of fact, the film was neither obscene nor was its portrayal of social evils a threat to public order. It directed Doordarshan to screen it, because it is a State institution and therefore would be covered by Article 19(1)(a).

In Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology v The Chairperson, Central Board of Film Certification, the Delhi High Court disapproved of the Board’s cuts on visuals pertaining to the destruction of the Babri Masjid in 1992 on the ground that those scenes promoted communal and anti-national attitudes. The High Court held that recalling the memory of a historical event cannot be a ground for excision, even if such a memory is imperfect or has the potential to revive tensions in society.

Freedom to speak involves the permission to narrate, the High Court held, adding that interpretations and constructions of the past may or may not be invoked for present political ends, but it is not for the province of the court to advance its own competing interpretation, and impose it upon everyone else.

In 2004, in FA Picture International v CBFC, the Bombay High Court came to a similar conclusion, striking down the Board’s refusal to certify a film about the Gujarat riots because it was a scar on national sensitivity and the film would aggravate the situation. The Court held that both the Board and the appellate tribunal had misconceived the scope of their powers.

“Films which deal with controversial issues necessarily have to portray what is controversial. A film which is set in the backdrop of communal violence cannot be expected to eschew a portrayal of violence,” the Court held.

It agreed that while exercising writ jurisdiction, it would ordinarily not substitute its view for the view of an expert. But it added that the foundation for its exercise must rest on its commitment as an expounder of constitutional principle. Where the decision of the CBFC entrenches upon the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression, it is not merely the function but the duty and responsibility of the court to intervene, the High Court held. It directed the Board to issue an appropriate censor certificate for the film, Chand Bujh Gaya.

The CBFC’s decision on Padmavati, therefore, has profound constitutional significance.