The basic structure discourse is a gift of judicial wisdom offered as the highest form of education of those wielding constituent power—the power to make changes in the Constitution but not of changing of the Constitution

By Upendra Baxi

Once upon a time, Constitution-makers subjected political power to some threshold of moral and constitutional discipline of inherent constraints. It seemed natural after the revolutionary conditions in America and France in the 18th century to utter words like “immutable”, “unchangeable”, “unalterable”, “irrevocable” and “perpetual” to describe certain constitutional provisions as unalterable or unamendable; in fact, the German constitution heralds “dignity” as ewigkeitsgarantie–“eternal”.

But everything is now under stress in Covid-crazy days and a runaway hyperglobalising modern world—everything is infinitely malleable, and nothing is anymore sacrosanct. And the vanishing present does not allow us to think of constitutions as a discipline on power; now what seems imperative is only unrestrained power of governance. We seem to live in an era of what philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche described (as “passive nihilism” of “devaluation of all values”). Passive nihilism simply marks globally the “will to power” and its every day pathological banalisation, and we tend to forget what he called “active nihilism”–the installation of new values.

The basic structure discourse is a gift of judicial wisdom offered as the highest form of education of those wielding constituent power to grasp the distinction between the power not just to make changes in the Constitution but changing of the Constitution itself. Instead, it has been regarded as an unwelcome intrusion in well-ordered governance.

Very recently, while speaking at the Second JB Dadachanji Memorial Debate in Delhi, Attorney General KK Venugopal said that “if constitutional morality still breathed, first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s fear that the Supreme Court will become the third chamber of Parliament might come true”. He felt that the Supreme Court “has garnered to itself vast power, which no apex court in the world has ever exercised”. As a most “powerful weapon that surpasses all the powers conferred” on it , Article 142 invests it with power to “complete justice” which is now treated as a “Kamadhenu” from which “unlimited powers flow”. Indeed, he further said: “The use of constitutional morality can be very, very dangerous, and we can’t be sure where it will lead us to. I hope constitutional morality dies.” (see Baxi, India Legal, December 16, 2018). This was a thinly veiled attack on the basic structure doctrine itself, as constitutional morality has been imbricated in this “moral reading” of the Constitution (as Ronald Dworkin calls it).

In earlier times, in 1973, the then Attorney General, Niren De, argued that Article 368 did not limit the plenary constituent power of Parliament to repeal or to amend the Constitution all the way as long as the procedure outlined therein was followed. Thus, he argued, that Parliament can amend the Constitution as it likes: it may convert the republic into a monarchy, secular into theocratic, democratic into autocratic, a sovereign into a subordinate, and rights-based into a rightless charter. In a wafer-thin majority (indeed if there was one!), six justices (named Ray 6) held that Parliament had such plenary powers, and six others (called the Sikri 6) insisted on implied limitations to amendability, with an ambivalent vote by Justice HR Khanna (which he retroactively amended in l975 in Raj Narain).

It was left to Justice Yeshwant Chandrachud as the chief survivor of Kesavananda, and also the longest-serving chief justice of India, to develop the doctrine of basic structure; and he did so in chiselled prose and strict discipline of constitutionalism ever since Raj Narain, through Waman Rao, Minerva Mills and beyond.

But it must be emphasised that the doctrine is a prize cultural export commodity. It has travelled far and wide. We learn from the narrative of Bangladesh development (see Ridwanul Hoque, Judicial Activism in Bangladesh: A Golden Mean Approach, 2011), how Justice Shahbudin Ahmad cited basic structure approvingly in voiding the Eighth Amendment (affecting the powers judicial review by decentralisation of its High Court decision). Subsequently, the 5thamendment (validating all martial law regulations), 13thamendment (which permitted transfer of all power to unelected authorities upon completion of the elected term) and the 16thamendment (pertaining to impeachment of Supreme Court Justices by Parliament) were all invalidated.

What is more, the Fifteenth Amendment Act, 2011, now protects from amendments the Preamble, all fundamental principles of state policy, all fundamental rights’ provisions and the provisions of articles relating to the basic structure—a provision that India may well emulate.

The evidence from Pakistan suggests that while there is a basic structure to its constitution, the Supreme Court has not yet invalidated any amendment on that ground. Yet, while considering a constitutional challenge to the Eighteenth Amendment (concerning a new procedure for judicial appointments) and to the Twenty-first Amendment (empowering military courts to try criminal cases of suspected terrorists), a majority of 13 out of the 17 Justices invoked substantive implied limitations. They proceeded to rule further that the Court may indeed identify the constitution’s salient features and determine the validity of any abrogation or substantive alteration of any of these features.

To these vignettes must be added the authoritative survey of Professor Yaniv Roznai, who has indefatigably identified many other situations of unamendability. He finds that “various courts from different legal traditions and jurisdictions, inter alia in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, have identified a certain constitutional core or set of basic constitutional principles that form the constitutional identity which cannot be abrogated through the constitutional amendment process”. “Of course,” he says further that “the Indian Supreme Court was the pioneer in this trend”. And he adds that even in Malaysia and Singapore, where courts have “rejected the entire notion of implicit limits, there exists a recent inclination towards the idea of implicit unamendability” (Yaniv Roznai, Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments, 69-70 2017).

The idea of “implicit unamendability” is the very essence of contemporary constitutionalism that Kesavananda, and its normative progeny, celebrates in a worldwide diffusion. In its various judicial avatars, the wisdom of the Supreme Court of India has found different verbal safe harbours. But the general idea has been that while the changes in the Constitution should follow the procedure prescribed for amendment, changes of the Constitution must not stray beyond the boundaries of the preservation of its basic identity.

The moral maxim animating the spirit of the basic structure is that all powers are constitutional powers; these must share equally the opportunities and responsibilities mandated by the Constitution. All constitutional powers are supreme within their own sphere. Not a single constitutional power, including the judicial, is above the Constitution. The Supreme Court of India has tirelessly reiterated: “Be you ever so high, the law is above you.” But the idea of the spirit of the constitutional schema is always to be read in, and through, the provisions of the Constitution.

A favourite passage of mine occurs in the Raila Amolo Odinga (2017) Kenya decision voiding a presidential election for violating the framework of free and fair elections. Chief Justice David Maraga said that the “Supreme Court’s consistency and fidelity to the Constitution was an unwavering commitment” which led to nullifying President Uhuru Kenyatta’s election for a second term in office, while also giving 50 days to plan and hold re-election, whose results in the incumbent’s favour were later upheld. In his reading of the majority judgment, the learned chief justice said that it would be “a violation of the cardinal constitutional principles if the delegated powers were deployed dishonestly”.

He memorably added: “However burdensome, let the majesty of the Constitution reverberate across the lengths and breadths of our motherland; let it bubble from our rivers and oceans; let it boomerang from our hills and mountains; let it serenade our households from the trees; let it sprout from our institutions of learning; let it toll from our sanctums of prayer; and to those, who bear the responsibility of leadership, let it be a constant irritant.”

Instead of burying five fathoms deep—were it constitutionally permissible at all—the task ahead is to make every generation alive and wise to the values inherent to this enunciatory enterprise. The doctrine as it has developed does not betoken any arrogant judicial overreach or sovereign judicial despotism. Indeed,there has been no instance of wanton judicial review power which has prevented the plenary powers of governance from proceeding with the tasks of just development. The judicial powers, on all evidence, have been used sparingly, and with notable courage and craft though amidst contention the Nehruvian apprehensions have not come true. And the lack of finalisation of the memorandum of procedure in judicial appointments (mandated by the NJAC Case) shows, in my opinion, how a determined executive can usher in a diarchy where the executive wields as substantial powers as the judicial collegium.

Chief Justice Maraga’s words should resonate well amongst the constitution’s curators, custodians and connoisseurs. The tasks of constitutional elites everywhere lie in preventing constitutional dismemberment in the name of amending a democratic constitutionalism and in enhancing the arts of governance amidst the

“constant irritant” of the well-considered judicial discourse about constitutional good governance.

—The author is an internationally-renowned law scholar, an acclaimed teacher and a well-known writer

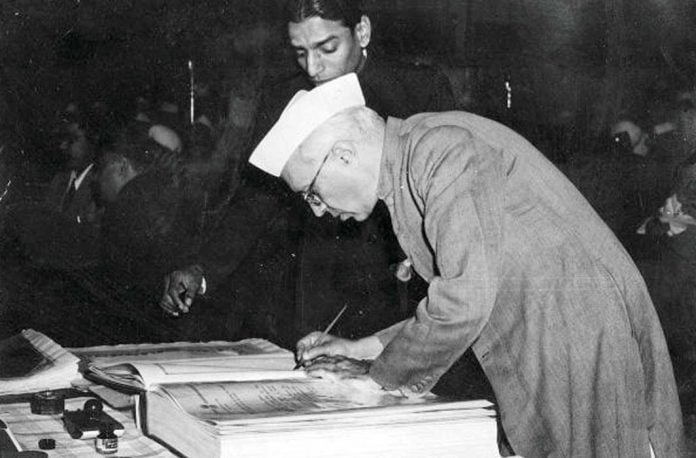

Lead picture: Jawaharlal Nehru signing the Constitution whose basic structure needs to be maintained

Photo credit: Wikimedia