The country of origin or manufacture stamp on products on sale on E-Commerce sites is a prerequisite in India. What happens when it is only true for the stamp?

By Sujit Bhar

A recent petition before the Delhi High Court has the potential to further open a Pandora’s Box and add to the chaos that has ensued amid the recent public outcry against China-made products. While the government seems clear about its objectives, that no ban on import of essential Chinese products would immediately ensue for obvious purposes, a possible hit on E-Commerce sites cannot be ruled out.

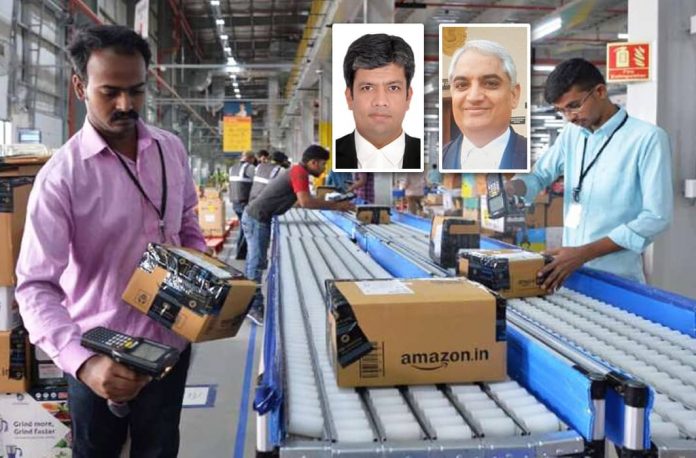

The petition, filed by advocate Amit Shukla before the division bench of Chief Justice DN Patel and Justice Prateek Jalan, alleges that E-Commerce sites in India are not adhering to the Legal Metrology Act, 2009 by not mentioning the name of the manufacturing country on products being sold. He explained that “the E-Commerce and E-Commerce Entity is defined in Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules, 2011. The E-Commerce Web Sites / Applications are in public domain and are accessed by public at large for the purposes of buying and selling of consumer goods and other goods online.”

The plea also states that in 2017 the Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules, 2011 was amended and it was made mandatory to publish the country of origin of the manufacturer on the e-commerce website. He said that the companies have not been adhering to this rule. The development on Wednesday (July 1) was that the bench has issued notices to the Centre, Flipkart, Amazon, Snapdeal and other e-commerce companies to this effect.

In the face of it, this could be mildly treated as a rather normal development and hardly noteworthy. In ‘normal’ times it would have drawn little attention. In the backdrop of the Chinese transgression in Galwan, Ladakh and India’s reply to that, however, this gains immediacy. While this plea can be treated in isolation as one simply wanting legal interference in the adherence of the act to the letter, it will certainly muddy waters for manufacturers from across the world (not just in China), who source most of their components from China, to do the final assembly. This will also apply to a large number of Indian companies that incorporate innumerable China-made components in what they finally assemble, or even import completely knocked down (CKD) kits and assemble them in India, resulting in a somewhat specious ‘Made in India’ tag.

The matter comes up for hearing on July 22, but before that one can investigate the possible pitfalls that lie ahead.

The ‘Manufacturer’ conundrum

In today’s world, the manufacturing country need not even be the assembling country and vice-versa. This is not only typical for electronic gadgets (including phones) that are sold on E-Commerce sites, but they extend to white goods engineering tools, specialized equipment and even motor vehicles.

The amended rule (of 2017) said that ‘in rule 6… (b) after clause (a), the following clause shall be inserted, namely:- “(aa) The name of the country of origin or manufacture or assembly in case of imported products shall be mentioned on the package;”…

That’s fair enough information for the consumer, who would want to know where the product has been sourced from. As per consumer protection laws, the consumer has legal right to such information. But the underlying issue is somewhat different. If, say, a product is marked as imported from Taiwan (Made in Taiwan tag), one has to keep in mind that Taiwanese businessmen have invested millions, if not billions of dollars in mainland China to set up massive factories so that cheap, efficient and abundant labour is available to help manufacture these. So, while the product will be sourced from Taiwan, it would essentially be made wholly in China.

This aberration would be further magnified by the fact that even iPhones would be made in China and any trouble in sourcing that would mean further disruption of international trade. In the Android field, the huge, spanking new Samsung plant (an extension of an old plant) in Noida, India, inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi just about two years back (it is said to be the largest mobile phone plant in the world), sources many of its phone components from China. This means that while the origin of the phone is India, it is chock-a-bloc with Chinese parts. How would one deal with that if public outcry reaches fever pitch?

There is obviously a middle path. Otherwise E-Commerce, as we know it, may come to a grinding halt in India.

According to Kaustubh Shukla (Picture inset top left), Advocate on Record at the Supreme Court, the Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules (amended 2017) apart, section 79 of the Information Technology Act would come into play here. “E-Commerce sites would essentially be considered intermediaries in this business. While this section deals with instances in which such intermediaries not to be liable, it as a corollary also explains instances where these intermediaries WOULD be liable.”

Sub-section 1 of s 79 says: “(1) Notwithstanding anything contained in any law for the time being in force but subject to the provisions of sub-sections (2) and (3), an intermediary shall not be liable for any third party information, data, or communication link made available or hasted by him.” However, sub-section c clarifies: “(c) the intermediary observes due diligence while discharging his duties under this Act and also observes such other guidelines as the Central Government may prescribe in this behalf.”

This is bolstered in Section 79 (3) “(3) The provisions of sub-section (1) shall not apply if—

“(b) upon receiving actual knowledge, or on being notified by the appropriate Government or its agency that any information, data or communication link residing in or connected to a computer resource controlled by the intermediary is being used to commit the unlawful act, the intermediary fails to expeditiously remove or disable access to that material on that resource without vitiating the evidence in any manner.”

According to Shukla, this is a legal angle that could allow the court to intervene. “However, let us realize that the court would be interested in the in the letter of the law and these sections would help in making up the court’s mind. However, beyond this legal scope, there would be issues that need to be understood,” he said. “One has to take into consideration hat India is a signatory to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which covers international trade in goods. Stipulations there would come into play if the issue blows up into an international one.”

Shukla is probably right in pointing out the limitations of this domestic public frenzy. He points out that the workings of the GATT agreement are the responsibility of the Council for Trade in Goods (Goods Council). This Goods Council is made up of representatives from all WTO member countries, including India and China. Any transgression on this could end up as expensive mistakes for India.

At the same time, informed choice is virtually a fundamental right of the consumer. Hence, he/she should be in the know of the antecedents of what he/she buys before making up his mind.

“As for the High Court so far, as I see it, is a legal one, and pretty straight,” says Shukla. “It is required by law that the country or origin or manufacture be stamped and this is perhaps all the court at this point would be rightly interested in. But remember, considering e-commerce sites as intermediaries, the follow-up would be noted in taxation issues. Each type of component would have different import duties and there will be a money trail that can easily be tracked. If such an appeal does come up later, the court could take this route and provide a direction.

“However, with millions of goods uploaded for sales on sites such as Amazon, it would be very difficult to trace each and every one back to its origins. Companies such as Facebook and OLX have teams to check each item put on sale. But the sheer size of Amazon, say, would make this incredibly difficult,” Shukla said.

“The line the court would probably take is the obligation issue. The seller and the intermediary have obligations to keep the customer informed about the product’s antecedents,” he added.

Neeraj Sharma (Picture inset top right), Advocate Supreme Court, agrees that within the court’s legal ambit the route s straight. “The directive from the court is based on law and the court quite rightly did so. Non-adherence to the rules laid out will be taken into account by the court. The court, I believe, would not see further in this particular appeal,” he said.

“For the issue of the stamping of made in a particular country, I think this has to be dealt with in Parliament. Frankly, this would be a long term affair that a mere legal insertion would not solve. Production cost of local components would be way higher and less competitive.”

He agrees that this ‘loophole’ remains within the system. “In the current globalised world, with stipulations accepted at the WTO, any sudden move could be a tricky one. For that we need to remain careful.”

Till such time, the Made in… stamp would remain contested.