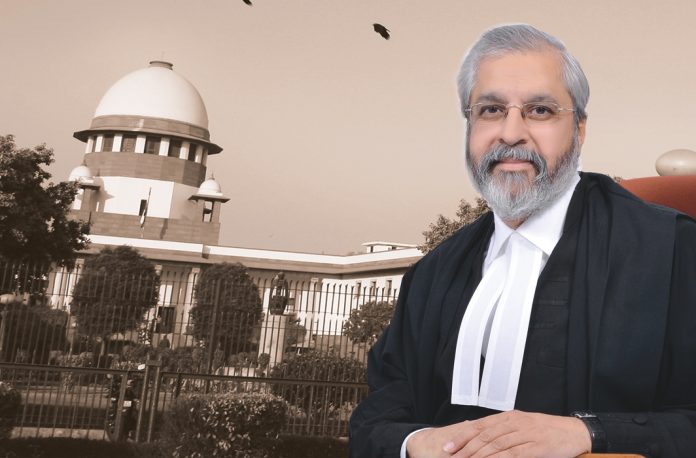

Justice Madan Lokur’s recent article criticising the “present-day functioning” of the Supreme Court for not behaving like a super-executive and not playing interrogator-in-chief to the Government of India over the migrant crisis, is one of the most dishonest and constitutionally perverse opinion pieces I have read since the crisis set in. In summary, his article takes the suo motu migrant order of May 26, 2020 of the Supreme Court to argue that the Court ought to have intervened immediately in the government’s handling of the migrant crisis. He then argues that the Court should have donned the mantle of a prosecutor and asked “pointed questions to the State” and sought a “plan of action” listing “steps taken and proposed to be taken to mitigate the hardships that the migrants faced,” and finally, whether “state governments were geared up for the massive influx of migrants”. These judicial orders, in his view, ought to have been issued in the form of a writ of continuing mandamus, effectively transferring executive control into the hands of the judiciary.

In his view, the failure of the Court to pass such proactive judicial orders, at the very inception of the national lockdown, had earned the Court a failing grade—‘F’. While Justice Lokur is entitled to state his views about the Supreme Court and its approach to the migrant crisis, the very basis of his criticism is at complete variance with well established principles of the Constitution—a document he swore an oath to uphold and protect. Lokur disregards the fact that the Indian Supreme Court, whilst conceived as a rights court, conferred with original jurisdiction by the members of the Constituent Assembly, was never intended to function as a super-executive or a super-legislature. He ignores, perhaps deliberately, the earliest stand taken on this seminal issue by the Supreme Court itself.

In Re, The Delhi Laws Act, 1912 [AIR 1951 SC 332], a seven-judge bench of the Court considered the doctrine of separation of powers and observed that the Indian Constitution was modelled on the British parliamentary system, “the essential feature of which is the responsibility of the executive to the legislature”. Therefore, to expect, nay, earnestly believe, that it is the Court which ought to replace Parliament and take the government to task at the very inception of a crisis, is to negate the very soul of our democratic polity.

Similarly, in Ram Jawaya Kapur’s case 1955 2 SCR 225 at 235-6, the Court categorically held that our Constitution does not contemplate assumption, by one organ or part of the State, of functions that essentially belong to another. The Court used even stronger language in the decades that came after, going so far as to say that the power of judicial review cannot be misused “to usurp or abdicate the powers of other organs,” [1981] 1 SCC 568 at 584. In fact, this understanding that there were strong limits on the Court’s powers to interfere with executive and legislative action dates back to its very conception by the founding fathers. AK Ayyar, who was part of the Assembly’s five-member committee tasked with formulating the draft provisions establishing the powers of the Supreme Court, while repeatedly stressing the importance of judicial independence warned against confusing it with overzealous activism. While the need for a jurisdiction which entertained rights-based cases was accepted, Ayyar remained firmly against any interpretation which allowed the Judiciary to usurp legislative and executive functions. He was clear that “the Judiciary is there to interpret the Constitution or adjudicate upon the rights between the parties concerned…the Judiciary as much as the Congress (referring to US Congress) and the Executive, depends for its proper functioning upon the cooperation of the other two.” (CAD XI, 9, 837).

Time and again, the Indian Supreme Court has stressed the need for it to exercise restraint when it comes to its power of judicial review. In Kalpana Mehta v. Union of India, (2018) 7 SCC 1, the Court expressly stated that the duty of judicial review which the Constitution has bestowed upon the judiciary “is not unfettered”. The Court held that “the principle of judicial restraint requires that judges ought to decide cases while being within their defined limits of power. Judges are expected to interpret any law or any provision of the Constitution as per the limits laid down by the Constitution”. In an equally powerful assertion of this principle, the Court in Dr. Ashwini Kumar v. Union of India (Writ Petition (C) No. 738 of 2016) accepted the view that the three wings of the government do have separate and distinct roles and functions that are defined by the Constitution. It held that “all the institutions must act within their own jurisdiction and not trespass into the jurisdiction of the other…By segregating the powers and functions of the institutions, the Constitution ensures a structure where the institutions function as per their institutional strengths”.

The constitutional scholar, Professor SP Sathe, was scathing in his criticism of judicial overreach. In his book, he analysed how in many cases “the Court has taken over the legislative function not in the traditional sense but in an overt manner and has justified it as being an essential component of its role as a constitutional court”. He laments that “there are instances of judicial excessivism that fly in the face of the doctrine of separation of powers…broadly it means that one organ of the State should not perform a function that essentially belongs to another organ”. To this end, believers of the “activist” construct of the Supreme Court, such as Justice Lokur, often look towards its cases from the 1980s to justify broad-based interference in Executive action. They ignore the fact that the Court had itself warned against such an approach in many of those cases.

Justice Pathak (as he then was) repeatedly stressed the importance of judges acting with circumspection. In the Bandhua Mukti Morcha case, 1984, 3 SCC 161, which is a much cited precedent for those in favour of judicial activism, Pathak’s opinion is often glossed over, in which he cautioned against “succumbing to the temptation of crossing into territory which properly pertains to the Legislature or to the executive government…In the process of correcting executive error or removing legislative omission the Court can so easily find itself involved in policy making of a quality and to a degree characteristic of political authority, and indeed run the risk of being mistaken for one”. Speaking on what the Court’s approach ought to be while deciding emotive issues, which would be applicable to the present-day migrant crisis, what Pathak held was apposite: “There is great merit in the Court proceeding to decide an issue on the basis of strict legal principle and avoiding carefully the influence of purely emotional appeal. For that alone gives the decision of the Court a direction which is certain, and unfaltering, and that especial permanence that in legal jurisprudence which makes it a base for the next step forward in the further progress of the law.”

Justice Lokur’s expectation that the top court should have simply waved a magic wand and asked “some questions” and sought some “reports” and would thus have ameliorated the suffering of lakhs of migrants, is unrealistic and counterproductive. Justice SP Bharucha, at a lecture on public interest litigation, put it aptly when he said that “this Court must refrain from passing orders that cannot be enforced, whatever the fundamental right may be and however good the cause. It serves no purpose to issue some high-profile mandamus or declaration that can remain only on paper.” In deciding the initial batch of migrant related PILs, some filed by activists and others by politicians, the Court had little choice but to rely on the assurances made to it by the Government. At the very inception of a national crisis, no reasonable person could expect the Court to interrupt ongoing relief measures and transpose itself in place of the national executive as the arbiter of ideal governance—all-knowing and all-wise.

Notably, Justice Lokur has himself been guilty of this transgression. In the Swaraj Abhiyan case, (2016) 7 SCC 498, writ petitions were filed seeking relief for drought affected areas, where Justice Lokur significantly widened the scope of the list before it and then went on to consider the various technical permutations and combinations that led to a declaration of drought by state governments, and then unabashedly recommended such declaration to Haryana, Bihar and Gujarat. Not stopping there, he also went on to list various “water conservation” techniques such as “dry land farming, water harvesting, drip irrigation etc” which the states should consider. Since when is all this the domain of the Supreme Court? Paradoxically, in the same judgment, Justice Lokur concludes by accepting and acknowledging the fact that a constitutional court is to show judicial restraint in issues of governance (para 110), and yet he refuses to apply the same principles to the Court now that he has retired.

Thus, the disingenuity in Lokur’s arguments stems from a deep-seated ideological bias, which is anathema for any judge, be it a magistrate or one who wields dizzyingly broad powers as a justice of a constitutional court. Before you assume that I am referring to a political bias or a bias pertaining to economic systems, let me clarify that I am not. Justice Lokur’s bias appears to be more insidious than these, in that he earnestly believes that a constitutional court in a democracy is, to borrow his term, “obligated” to invade and tinker in the executive domain if it thinks fit.

In other words, Justice Lokur is an aggressive proponent of the all-powerful “activist court”, an unelected and therefore unaccountable organ of government, which arrogates to itself primacy in the constitutional scheme and awards itself unlimited and wide-ranging powers of intervention in all matters of State. While in theory these powers are circumscribed by limiting provisions, a judge who subscribes to the activist belief interprets them differently, often “expansively”, thus widening the range of issues it can run its writ upon. The migrant crisis too, from Lokur’s activist-constitutional viewpoint, was a situation that obligated the Court to intervene and monitor the executive—like a superior authority. Constitutionally, this belief is a total negation of our democracy’s most fundamental principle—the separation of powers between the organs of government. While the degree of separation in India is not as strict as the United States or Australia, even so, the entire system is built on “checks and balances”. The underlying belief of this system is the acceptance of the inviolable principle that power cannot be permitted to accumulate in any one organ of the State. It must devolve strictly as per constitutional rules.

—The author is an advocate practicing in the Supreme Court of India