By Vikram Kilpady

The day Delhi recorded the highest rainfall in January since 1989, Harish Rawat was doing back-to-back virtual campaigns on Twitter and YouTube. Necessitated by the campaign bar due to the spread of Omicron, the Election Commission of India’s (ECI) regulation had this veteran Congress leader, a former chief minister and a Union minister, lend his familiar visage for the poll pitch a few days after rival Harak Singh Rawat trooped back into the party. Not one of the aya Rawat, gaya Rawat school of politics, an Uttarakhand version of Haryana’s aya Ram, gaya Ram tradition of opportunism, Harish Rawat is shepherding the state campaign until the ECI lifts the bar on open campaigning. Though Rawat had decided not to contest, the Congress has declared him from Lalkuwan constituency instead of the previously announced Ramnagar seat, while bete noire Harak Singh Rawat’s daughter-in-law Anukriti Gusain Rawat will contest from Lansdowne. Harish Rawat’s daughter Anupama Rawat, has also been fielded from Haridwar Rural segment. The Congress, incidentally, is fighting 70 seats in the state.

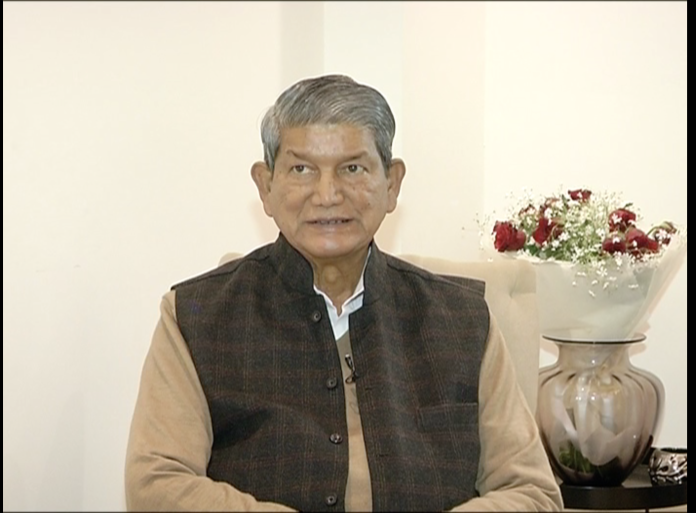

Rawat’s had a tete-a-tete with a small TV crew on the party’s stellar chances in the state aided by the overwhelming anti-incumbency against the BJP. Beaming, he’s confident that failure of the double-engine BJP will see the Congress trump them at the hustings. The fresh-looking flowers in the vase that line the camera frame are plastic and never to age; Rawat, a man of many winters, is sprightly and warm. Despite the still-intact hair and the wide smile, he is showing signs of the long day he has had in front of webcams.

There is a steady stream of visitors in white khadi, swaddled in pashminas and warm jackets and an assortment of caps, Himachali topis and woollens. The hangers-on nudge him away for another meeting with undisclosed leaders as the office-residence’s kitchen drops a clanger as tea and snacks are made to keep the 73-year-old buzzing and energetic.

Some 20 minutes later, the cook trundles out with water and says sahab will take some 30 minutes or even longer today. The gathered media contingent returns to their mobile screens, and those who didn’t, murmur their plans for a wintry Delhi evening. But fate has other things in store for them.

Harish Rawat returns after some 40 minutes, apologising profusely. He then takes the seat next to the vase, bang in the camera’s sights, and checks the lapel microphone. Interviewing him is colleague Sanjay Raman Sinha, who has been wondering how his silver stubble would look onscreen. This reporter is sitting behind the camera and observing the interview.

The initial questions to warm the subject up are harmless like what’s up with the grand old party’s campaign in a state with a very strong anti-incumbency against the ruling BJP. Rawat says candidates have been chosen, the party will release their names shortly.

Responding to the agenda of the party, the veteran Congressman expresses dismay at the havoc the BJP has left the state reeling under. He says vikas is lying dead, referring to the BJP’s promise of vikas that has been in fits and starts, and no-starts in some places, especially Uttarakhand. He frowns at the ignominy the Kumbh has had to suffer for the Covid-19 testing scam which made front pages elsewhere and on the corruption that led to the scam. Rawat blames the BJP, as he is expected to, but doesn’t stoop to the level of a newbie dilettante; no blame is laid at individual leaders’ feet but at the BJP’s colossal collective failures.

He then makes a pointed reference that the rich, the Ambanis and the Adanis, have made more wealth in the price rise that has left the poor destitute. It takes him some effort to recollect the difference in the price of cooking oil during Congress rule and now. It comes, but Rawat hides his impatience with his memory, turning pages as it were in some notebook in his mind, by his steady gaze at the floor.

The charges roll off his lips with practiced ease, again the effortlessness of a campaigner marshalling the big ticket points and ticking them off with panache to the crowds’ fawning. But there is no crowd here, just journalists nodding away with each point being made vehemently yet politely.

Just when Rawat is scoring metaphorical runs, his aides rush in with all intention to smother the interview, at least for a bit. Someone high and mighty from the party wants to confer. The iPhone is cradled like the expensive toy that it is, with the leader on the other end holding as Rawat finishes making his point. The production crew is handed a paper with the name of a high command factotum scrawled in black ink, people who can crane their necks try to read the name, some give up at the handwriting and the task it is to decipher it upside down. The interview is then paused.

Rawat glides into the adjoining bedroom, enveloped by his aides, who latch the door behind them. The tension is visible on their faces. Perhaps the patriarch was back imploring the party’s factotum to ensure them a chance this year.

With no chief ministerial face being declared, Rawat has been at the centre of attention, a firm contender himself. He’s left it to the party’s wishes. Maybe he will put in his all to bargain for his offspring and leave the rest for later. A hush descends on the living room. The harsh lights and their heat add to the discomfort of those in their masks, some N95, some cloth, fearing Omicron’s velvet touch. Dusk is folding itself into a rainswept night, distant traffic moves in faint symphony.

Rawat returns, again apologising, old world charm and manners holding fast even as age is chipping away at the limbs. My colleague has warmed up enough and goes for the jugular. What about the one family, one ticket theory this time? Your son and daughter want to contest too? He doesn’t budge or shy away from it; they’ve worked their way to cultivate constituencies which have never voted for the Congress, he says. They have put in real hard work to make their presence felt. Surely, they should be rewarded, Rawat underlines. But the party will take the decision, and we will go with it.

Again when asked why he chose to put out an ambiguous tweet on his alienation within the Congress a few weeks ago, Rawat’s gaze is upright and firm. I’m a Nehru Gandhi family loyalist and I will remain one till I die, he says in an obvious reference to the many leaders who have switched over to the Trinamool Congress in Goa or elsewhere to other options. He justified that it fell upon him as a senior leader to say what he wanted through a tweet. The wish was to retire and not to jump ship like rats, a reference not lost on the gathered with the return of Harak Singh Rawat to the party from the BJP. Harak Singh had queered the pitch for Harish Rawat when he was chief minister and he was back to harvest an anti-incumbency against the very government he was part of till last-to-last week.

A question on the factionalism in the party draws an exasperated sigh from the gathered. More MLA hopefuls and their relatives are on the stairwell trying to meet his eyes while the interview is on. Time’s ticking, the list is near final and Akbar Road is very far, Harish Rawat’s South Delhi home is an easy destination.

Rawat soaks in the expectant glances. After the phone call, he’s a different man. Something is certain, he doesn’t reveal what. But he’s now attacking the BJP for claiming credit on the all-weather roads project for the Char Dham. The humour suits the increasing gathering as he savages every claim of the Uttarakhand BJP and says all were Congress projects: Banihal, Mangalyaan. All UPA projects, someone else took credit. The BJP claim of developing Uttarakhand is as true and real as the Rs 15 lakh that is yet to come, he says with a twinkle in his upturned eyes.

The late Chief of Defence Staff General Bipin Rawat’s brother shouldn’t have joined the BJP, he says. Their father was a man who was Congress-inclined. Now to lose it all by joining the BJP, he tut-tutted.

Coming to the attack of the BJP on the Amar Jawan Jyoti flame dousing, Harish Rawat chooses to bat it down. Martyrs’ issue is very serious, can’t create political controversies, he says. Now the patriarch is impassive, having shielded away autumn, winter. Spring lies ahead and in Dehradun on March 10, it will be a bounty of brahma kamals.

But for now, Harish Rawat is in fine balance, confident and calm!