Single women and widows are often branded as witches to humiliate and ostracise them and seize their property. Why does this reprehensible practice continue unchecked and are our laws stringent enough to provide relief?

~By Shankar Sinha and Meha Mathur

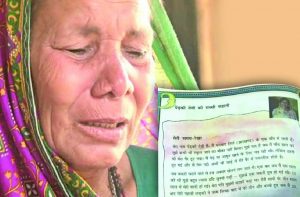

“My name is Pedki Devi. I live in a village in Jharkhand. When I was 15, I was married off. My eldest daughter was born three years later and subsequently, I gave birth to three more children. When I was 35, life came to a standstill when my husband died after an illness. Following that, my husband’s brothers tried to seize our land. They beat me up brutally and labelled me a witch. I filed a case against them. At the age of 40, I saw a police station for the first time. I learnt how to read and write at the age of 45. Now I am 50 years old.”

This testimony is not recorded in a police report but is part of a math textbook, Ganit ka Jaadu (The Magic of Maths), of the Jharkhand Education Project for Class III students. And the unfortunate story is followed by an exercise in which students have to mark, next to an illustration of a woman, the milestones of Pedki Devi’s life.

The cruelty of it is that it is not fictional. The real life Pedki Devi is still running from pillar to post to get justice against the atrocity perpetrated against her in 1999. Like so many other cases of crimes against women being relegated to mere statistics, this case too has been reduced to an exercise in a textbook for school students.

But the humiliation and cruelty that Pedki Devi of Kherabera village endured in March 1999 has not been captured in the bland account in the textbook. She can, however, still recall the day when her husband’s brothers pounced on her as she was returning from the fields. They dragged her and stripped her, forced her to ingest excreta and urine and beat her mercilessly. They conveniently branded her a witch—the evil force that killed her husband.

When her daughters saw their mother being assaulted, they rushed to her rescue, but they too were beaten up. One of them, Purni, suffered a miscarriage as a result. Pedki Devi spoke to India Legal’s sister channel APN, about the pain and humiliation meted out to her some 18 years ago. And as she faced the camera in front of her ramshackle mud home, one could see the 12 acres of land which had become the bone of contention. Pedki Devi vividly remembers the spot where she was publicly humiliated.

Neighbours are either unwilling to talk about the incident or are petrified to express their support. One aged woman who saw Pedki Devi distraught on the ground, covered with excreta over her face and had offered her water, now categorically denies she saw any crime being committed. She says she had merely offered water to a woman in distress. And one of the accused, Srikant Mahato, denies being present in the village on that fateful day in 1999. He also denies that he or his family members were after Pedki Devi’s property.

But the truth lies elsewhere and it came into the public domain because Pedki Devi filed a case and decided she would not take the humiliation lying down. In 2004, a trial court sentenced the culprits to one to four years in prison. But they went in appeal to the Jharkhand High Court which granted them bail.

CASE DITHERS

Unfortunately, Pedki’s lawyer dithered, for reasons best known to him, in pursuing the matter in court. He did not inform his client about the hearings and as a result, she failed to turn up in court twice on appointed dates. The case soon lost direction. Meanwhile, the emboldened in-laws began to openly threaten Pedki and her family with dire consequences. There are allegations that they may have had a hand in ensuring that the case languished in the courts.

It is clear that seizing property was what motivated the in-laws to label Pedki Devi a witch. While rural societies, where superstition reigns supreme, do resort to occult practices to “neutralise” evil forces or for healing purposes, the branding of old and widowed women as witches is a matter of convenience. Often, the real motive is to throw them out of their property or to abandon them if they are becoming a financial burden for the family.

Branding women as witches is more of a tool used by land grabbers to deprive families of their property. It is also used as a weapon of revenge against women who refuse to yield to sexual advances

Arun Kumar Naik of Jeet, an NGO that is working in Jharkhand, explains the modus operandi: a scare is deliberately created around a person, usually an old destitute woman. At times, young women are also targeted as witches, and in such cases, the motive is more often than not sexual exploitation.

Once branded, the woman becomes an outcast in her own village and is ostracised.

The problem is not endemic to Jharkhand alone. One hears similar stories from across the country—of women being branded as witches and blamed for the death of a family member, the failure of a crop or any other untoward incident.

SOME EXAMPLES

Here are a few illustrative instances:

- Badar village, Balrampur district, Chhattisgarh, 2016: A 35-year-old woman is beaten to death by her brother-in-law and his son on suspicion that she is responsible for a child’s death

- Mayangi village, Odisha, 2015: A 35-year-old woman is accused of being a witch and forced to eat excreta

- Anglong district, Assam, 2014: A gold medalist in javelin who represented the state in several national meets, is tied up in a fishing net and brutally beaten up by villagers on suspicion that she indulged in witchcraft

- Smit village, Shillong, Meghalaya, 2013: Twelve persons arrested for the lynching of three in a case of witch hunting. The accused were reportedly related to the victims

The statistics from various states on witchcraft-related murders is, to say the least, shocking (see box). However, the situation in Jharkhand is the worst. Social activist Ajay Kumar Jaiswal, who has been working at the grassroots level in the state for the last 26 years says that his team surveyed 332 villages last year and found 300 cases of women being harassed as witches. He says: “Jharkhand has 32,000 villages and every village has such cases. So, thousands of women are suffering. We need a very big awareness campaign to eradicate this problem.”

The statistics from various states on witchcraft-related murders is, to say the least, shocking (see box). However, the situation in Jharkhand is the worst. Social activist Ajay Kumar Jaiswal, who has been working at the grassroots level in the state for the last 26 years says that his team surveyed 332 villages last year and found 300 cases of women being harassed as witches. He says: “Jharkhand has 32,000 villages and every village has such cases. So, thousands of women are suffering. We need a very big awareness campaign to eradicate this problem.”

Dr Louis Marandi, Jharkhand’s minister for social welfare, women and child development and minority affairs says the government is doing its bit through campaigns using street theatre and workshops. But, she admits it will be a long haul: “We can’t eradicate the problem completely. We can’t be watching over people 24 hours a day,” she says adding that she has no knowledge of the Pedki Devi case. “If you give us all the papers and her story, we will try to provide her protection through the local administration.”

Jharkhand is among the few states to have enacted a specific law—the Prevention of Witch Practices Act, 2001. Other states also have laws in place to counter the malaise (See box). But these have not had the desired impact.

This is perhaps why activists like Jaiswal point out that the new law is not an effective deterrent in Jharkhand. “One year of punishment and Rs 2,000 as fine is hardly a punishment.” According to him, a more stringent punishment is required like the Rajasthan Prevention of Witch-Hunting Act, 2015 which provides for seven years rigorous imprisonment extending up to a life term, and/or Rs 1 lakh fine. This, he said, is more in keeping with the nature of the crime.

Laws and limitations

There are several laws that deal specifically with witchcraft and “witch” related offences. The first was the Prevention of Witch (Dayan) Practices Act 1999 enacted by Bihar. Later, when Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand were created in 2001, they too enacted laws to address the witches issue. Both adapted the 1999 Act.

Jharkhand introduced the Prevention of Witch-hunting (Dayan Pratha Act) in 2001 and Chhattisgarh passed the Tonahi Pratadna Nivaran Act in 2005. Later, some other states followed suit.

It was a high court directive to Odisha that led to the enactment of the Odisha Prevention of Witch-hunting Act 2013. The Odisha initiative was followed two years later by Rajasthan passing the Rajasthan Prevention of Witch-hunting Act 2015. In the same year, the Assam Witch-hunting (Prohibition, Prevention and Protection) Bill was passed and awaits enactment since it was sent back to the state by the Union home ministry for review.

Two bills—the Maharashtra Prevention and Eradication of Human Sacrifice and Other inhuman, Evil and Aghori Practices and Black Magic Bill and the Karnataka Prevention of Superstitious Practices Bill—have been passed but not yet enacted. Both address the problem of witch-hunting.

So far so good. But the big question is how effective are the enacted laws on the ground? Partners in Law, a Delhi-based legal resource group working in the fields of social justice and women’s rights, conducted an 18-month study in Jharkhand, Bihar and Chhattisgarh. Their 2015 report—Contemporary Practices in Witch-Hunting: Social Trends and Interface with Law—spells out the problem areas in laws dealing specifically with witch-hunting.

The study reveals what is wrong with the criminal justice system. For example, in one-third of cases, the victims never approached the police or were prevented from doing so by vested interest or relatives. Many of the cases registered were closed because of shoddy investigation, lack of evidence and witnesses or a compromise being worked out between the victims and the perpetrators.

It is only when publicly orchestrated violence occurred that the police took it seriously. To quote the report: “Based on our data, we can infer that the law interacts with victims only when physical violence involving public humiliation is involved, but such cases do not proceed to the appellate courts unless they pertain to or result in murder.” In short, the state does not normally appeal against acquittal in cases of witch-hunting.

According to the report, the special laws on witch-hunting on paper focus on preventive action and addressing harassment where the motive is clearly linked to “witch” accusation. These laws criminalise the acts of “identifying” and “exhibiting” any person as a witch along with the mental and physical torture which accompanies it. All the offences under the special laws are cognisable and non-bailable. They seek to prevent escalation of victimisation through early intervention by the police.

However, very few reported cases are registered under the new laws. The study examined 85 FIRs and found that only six were registered solely on the basis of special laws. Notes the report: “The data categorically shows that the mischief that the special law was enacted to correct remains unaddressed, with no action or prosecution against preliminary forms of harassment. In fact, the data establishes that special laws are rarely, if ever, used alone, and almost never at the preliminary stages to prevent escalation of violence. Our data from police records show that almost all cases are registered under provisions of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), with one or more provisions of the special law, to establish if it (witch-hunting) were the motive of the crime. The majority of the provisions of the IPC invoked in the records are related to beating, hurt, trespass, theft, murder, conspiracy, etc—with more bailable rather than non-bailable offences being invoked.”

According to police officials, the IPC is invoked since the special laws are not comprehensive enough to deal with defamation, trespass, intimidation, vandalism, destruction of property or murder. So, even when the new laws are invoked, it is in conjunction with the IPC. The police find it easier to frame their cases under the existing laws.

Sashiprava Bindhani, Odisha’s information commissioner, who filed a PIL in the High Court which led to the enactment of the special law in the state in 2013, speaks of how women who break from conventions are usually the targets of witch-hunts. “Having grown up in the Mayurbhanj district of Odisha, I observed the exploitation perpetrated through witch-hunting against women who threatened social structures.” She is of the view that since the legislation has come there is some change—cases are being registered and people are sympathetic to the victims. However, legal experts do not see any dramatic change.

So, have the special laws helped? Madhu Mehra, executive director of Partners in Law, and Anuja Agarwal, associate professor, department of sociology at Delhi University in a joint paper published in The Economic and Political Weekly have this pertinent observation to make: “The parading of women, tonsuring the hair and blackening the face are forms of violation that involve more than physical injury, as they intend and result in humiliating the victim, destroying her social standing and dignity in the community. These need to be part of the penal code, given their social resonance—although largely associated with caste atrocities perpetrated against Dalits, there is increasing evidence that such victimisation is also used to punish social and sexual transgressions, which may or may not take the form of witch-hunting.”

Thus, the new laws may have filled a legal vacuum but do not look at the socio-economic situation that encourages witch-hunting. It is known that it thrives in areas where there is lack of education, economic depravity, health facilities and access to justice. But the criminal justice system continues to see the malaise as one rooted in irrational, barbaric practices and superstition. This is even reinforced in several judgments, one of which calls it a tribal custom of the “Middle Ages” which is perpetuated till today.

Any law or amendments made to an existing Act has to factor the socio-economic context rather than see witch-hunting as merely an irrational act guided by superstitious beliefs.

Also, the motives for witch-hunting have changed over the years. Laws have to take into account the present-day reality.

THE ORIGINS

Tribal societies always believed in the tradition of good and evil spirits. The good spirits, it was believed, could bring about wellness in the community and heal people. The evil forces, on the other hand, could wreak havoc and cause natural disasters like floods, famine, disease or drive away the rain. In tribal communities, it was a woman who was endowed with the power of healing.

Tribal societies always believed in good and evil spirits. The good spirits augured wellness and heal people. The evil forces could wreak havoc and cause disasters.

However, the line between good and evil was always a thin one. Traditionally, it was the all-knowing “Mahan” or seer of the village who identified the woman with the evil force residing inside her. She would be branded as a witch, paraded naked and killed and her family members ostracised. Anthropologists like KS Singh, former director of the Anthropological Society of India, have been quoted as saying that the concept of black magic and white magic got further underlined after India became colonised by the European powers.

Subhash Mendupurkar, director of the Society for Upliftment through Rural Action (SUTRA), has worked extensively in Jharkhand. He traces the problem to lack of medical care. “Medical facilities have not reached many parts of the country. And in Jharkhand there is a deep-seated belief that some people have the supernatural power of healing as well as destroying things. So, if something goes wrong you end up blaming that person. Once modern medical facilities are made accessible such beliefs will fade away,” he says.

But today, branding women as witches is more of a tool used by land grabbers to deprive families of their property. It is also used as a weapon of revenge against women who refuse to yield to sexual exploitation. Also, the campaign of a political party is sometimes derailed, particularly within tribal areas, by branding one of its activists as a witch. Such exploitative behaviour is sought to be explained as part of local customs and therefore, acceptable.

While stringent laws will help, changing societal attitudes and mindsets is the real challenge. Forget a tribal state like Jharkhand, we have a situation where even in a cosmopolitan city like Mumbai, a leading Bollywood actor was recently accused of practicing witchcraft by her embittered ex-boyfriend.

Superstition, as they say, runs deep. And there are enough people waiting to exploit the vulnerable.

—With inputs from Rafi Sami and Irfan Amayur