The Additional Solicitor-General intervened between Monsanto and Nuziveedu Seeds, giving the impression that the ministry is playing favourites. But this may not be the full picture

~By Vivian Fernandes

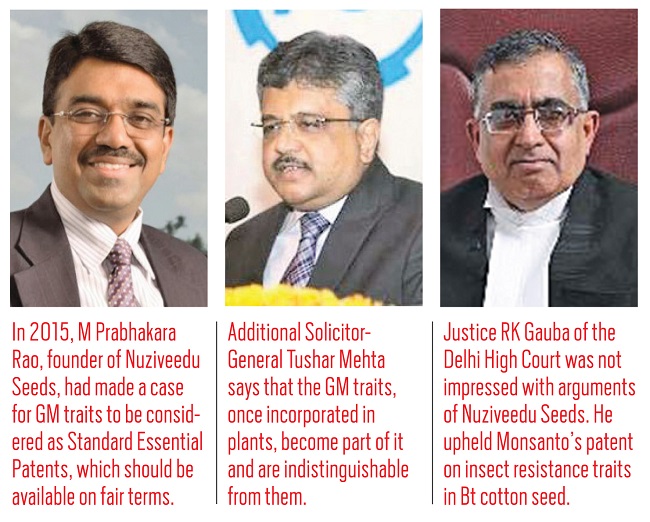

On May 16, when Additional Solicitor-General Tushar Mehta sought to intervene in a private dispute between Monsanto and its biggest erstwhile sub-licencee, Hyderabad-based Nuziveedu Seeds, it seemed like the agriculture ministry was not done with “fixing” Monsanto.

Monsanto, an American company, is the leader in genetically-modified crop technology. In December 2015, its local joint venture had terminated Nuziveedu’s licence over refusal to pay trait fee dues as per their contract. Mehta wanted to make submissions on behalf of the government on the patentability of genetically-engineered traits like insect resistance and herbicide tolerance in plants, a week after hearings on the matter had ended. But the Delhi High Court did not take them on record. It told him to move an application to do so and said the principal parties would be entitled to reply.

Incidentally, the views of the ASG and M Prabhakara Rao, the founder and managing director of Nuziveedu Seeds, are quite similar. In 2015, Rao had made a case for widely-used GM traits to be considered as SEPs (Standard Essential Patents) which should be available on FRAND (fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory) terms. He was quoting from an article in the August 2014 edition of the Colorado Law Review. Rao has also been pushing for the traits to be patented under the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights (PPVFR) Act.

STANDARD ESSENTIAL PATENTS

India has protected these genetically-engineered traits under the Indian Patent Act, as amended in 2002 and 2005. But the ASG believes that is not good for the country’s food security. He asserts that Monsanto and its licencees want to cling on to protections under that Act because they are addicted to profiteering. He wants widely used proprietary GM traits to be regarded as SEPs like the technologies used in smart phones, available freely on payment of a fee fixed by the regulator. Monsanto’s bollworm-resistance trait, for instance, is found in almost all the Bt cottonseed planted in the country.

Though the ASG agrees the traits by themselves and the method of putting them in plants can be patent-protected, once inside, they become part of the plant. Except for microorganisms, the patent act does not allow animals and plants, including seeds, and species to be patented. Nor can biological processes be patented. The ASG was referring to a list of “exclusions” in the act.

The ASG says GM traits once incorporated in plants, become part of it and are indistinguishable from them. Rao, like the ASG, believes they lose their distinct character once grafted into plant DNA. And the plants pass on the genetic traits to subsequent generations through a biological process, which again puts them in the excluded category. Hence, the correct law, according to the ASG, for protection of GM traits is the PPVFR Act of 2001. If a proprietary GM trait is used by any breeder (that is say, a seed company like Nuziveedu) in any of the seeds it registers with the PPVFR Authority, the trait developer can make a claim for “benefit sharing” on the authority. The PPVFR Authority will make payments from a National Gene Fund, made up of contributions by seed companies registered with it.

WITHOUT PERMISSION

The ASG believes the PPVFR Act allows seed companies as breeders to use the proprietary traits in their own varieties and hybrids without permission. But this is only for limited or one-time use. Once the traits are introgressed (transfer of genetic information from one species to another), the seed company will not need to use the genetic material of the trait developer. In other words, he seems to be making a case for legalised grab of IPRs.

But Justice RK Gauba of the Delhi High Court, against whose order the two litigants had gone in appeal to the division bench, was not impressed by similar arguments advanced by Nuziveedu Seeds. In his order of March 28, he upheld Monsanto’s patent on insect-resistance traits in Bt cottonseed. He said the patent act has a section on “invention” by which it meant “a new product or process involving an inventive step and capable of industrial production”. The provision was inserted in 2002 so that patentees were not deprived of the reward for innovations based on skill and ingenuity and “above what occurs in nature”. The GM traits involve “laboratory processes and are not naturally occurring substances,” Justice Gauba averred. They are man-made and therefore, do not fall within the ambit of exclusions in the patent act.

But Justice RK Gauba of the Delhi High Court, against whose order the two litigants had gone in appeal to the division bench, was not impressed by similar arguments advanced by Nuziveedu Seeds. In his order of March 28, he upheld Monsanto’s patent on insect-resistance traits in Bt cottonseed. He said the patent act has a section on “invention” by which it meant “a new product or process involving an inventive step and capable of industrial production”. The provision was inserted in 2002 so that patentees were not deprived of the reward for innovations based on skill and ingenuity and “above what occurs in nature”. The GM traits involve “laboratory processes and are not naturally occurring substances,” Justice Gauba averred. They are man-made and therefore, do not fall within the ambit of exclusions in the patent act.

The gene which produces the bollworm-killing toxic protein in Bt cotton plants is obtained from a soil bacterium. But the natural isolate cannot be straightaway inserted into the cotton genome. It has to be modified for the plant to accept it. It also has components attached so that the production of the toxic protein is switched on and off at particular points in the life cycle of the cotton plant. This gene construct when inserted can locate anywhere in the plant genome. There are hundreds or thousands of possibilities. The production of the toxin, its potency, the crop yield, its quality, and other properties of the plant can be affected by the location of the insertions. Each of these insertions is called an “event”. The event chosen after screening, for patenting, would be the one that gives the best set of desired results.

Justice Gauba said the PPVFR Act is for plant varieties. A plant variety, he said, is the lowest rank grouping of plants, distinguished from others by one or more characteristics. Relying on the 1991 international convention on protection of plant varieties, he said, a single plant, a trait (like disease resistance or flower colour), a chemical or other substance (like oil or DNA), or a plant breeding technology (like tissue culture) do not meet the definition of a variety.

Justice Gauba also termed benefit sharing as a “pot of gold at the end of the rainbow” because it depended on the breeders (seed companies) registering their varieties with the PPVFR Authority, which is not mandatory. Most seed companies, in fact, do not.

The ASG believes that once the traits are introgressed, the seed company will not need to use the genetic material of the trait developer.

Agribiotech companies say benefit sharing is for farmers and conservers of biodiversity. It is not for developers of GM traits which are manmade and created in laboratories. They say the law makes a distinction between the subject matter of an invention and use of an invention. If the subject matter is a plant or variety, it cannot be patented under IPA, but inventions whose use lies in plants and varieties can be patented.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST?

Incidentally, Rao was made a member of the PPVFR Authority in October 2016. He has been saying that seed companies should not have to obtain a non-objection certificate (NOC) from the trait developer, as it gives the developer a handle to impose onerous terms. Once the Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee recommends commercial release of a GM trait and the government accepts the recommendation, seed companies should be free to use the trait on terms fixed by the government and not the trait developer. Otherwise, it will result in a monopoly, he said.

On a reference by the PPVFR Authority, the ASG has opined that such an NOC is indeed not necessary. It is not prescribed by the Act. An NOC goes against the grain of the PPVFR Act, he says, which is to promote the development of new varieties and hybrids. He says a mere declaration is enough. This should not be construed as an NOC. A self-declaration that genetic material used in transgenic varieties has been lawfully obtained is enough.

Rao is said to enjoy considerable clout in the agriculture ministry, though this correspondent cannot vouch for it. His company was a big beneficiary (but not the only one) from the ministry’s 70 percent reduction in Bt cottonseed trait fees (payable to a joint venture of Monsanto). Bt cottonseed prices to farmers were cut by just four percent. Seed companies kept the savings.

Given the agriculture minister’s publicly stated dislike of Monsanto’s “profiteering”, it would be reasonable to assume that the ASG’s views have his consent. But a senior agriculture ministry official said on a non-attributable basis, that the minister has not given his approval to the ASG’s legal opinion and the ministry has not vetted it. “It is a private matter between two companies and the government has no locus standi in the dispute.” Since the agriculture ministry had issued a notification in May last year waiving patents on GM traits and then withdrawing the notification hastily, one cannot say for sure that the issue has been laid to rest.

—The author is editor of www.smartindianagricutlure.in