The intense juristic and judicial discourse around the Indian combat against Covid-19 places legal researchers also among the frontline of combatants against a sinister global pandemic. There appears to be a general consensus on the need for vast executive powers to fight this new menace. But equally, the implementation of the current lockdown raises many questions, especially concerning the dignity, livelihood and freedom costs for the impoverished strata (including necessitous migrants) which have been marred by some practices of the pedagogies of violence and inhuman cruelty. Economically, some of these concerns have been addressed by the Union of India, as the 2nd addendum issued by the home ministry (March 28, 2020) and clearly excludes significant sections of entrepreneurial agricultural activity from the lockdown regime.

The Supreme Court of India (SC) and many High Courts have already acted in many matters by exercising suo motu jurisdiction, which Professor Marc Galanter of the University of Wisconsin Law School earlier criticised for its “unprincipled nature” and causing disruption of “the normal operation of judicial hierarchy”. But he has now clarified (in a message to me on March 28) that he was criticising merely

those “initiatives” which were acts of “gratuitous grandstanding, frequently the expression of a single (Chief) Justice”. No such “grandstanding” is on display here.

The question that juristic discourse (the reportage in India Legal, Live Law and Bar & Bench, as well as deep analyses and granular reflections in Dr Gautam Bhatia’s posts in Constitutional Law and Philosophy) poses is, however, about the justification and constitutional limits of this power. It is not unpatriotic in the least to raise questions concerning the nature, scope, and limits of power and particularly to demonstrate how that power may be used to aggravate the violent social exclusion of marginalised groups. In fact, raising this awareness—self-styled super-patriots, please note—serves a democracy-reinforcing function.

Indeed, the immediate pre-Covid-19 jurisprudence of the Supreme Court speaks not of “good governance” but of constitutional good governance, which establishes the people-citizens of India as the real sovereigns whom all constitutional agents and institutions must serve. The judicial discourse on “constitutional renaissance” and “constitutional trust” (most notably articulated by Justice Dipak Misra) indwells in both normal and extraordinary times.

This does not mean that the judicial tasks are easy at all, given the eternal conflict between the wisdom of two astonishingly relevant Latin maxims: “Fiat justitia ruat caelum (Let justice be done though the heavens fall)” and “Salus populi suprema lex esto (The health of the people should be the supreme law or let the good (or safety) of the people be supreme or the highest law)”. If the latter maxim justifies conferral and exercise of vast executive powers, the primary function of courts and justices, however, remains the doing of justice and upholding difficult freedoms and complex rights.

LEGISPRUDENCE

The normative counter-insurgency against Covid-19 rests on the accumulated wisdom of legisprudence. Indeed,the mosaic of power rests on a combination of specific legislations against epidemics and disasters, leavened by multifaceted policy powers under the Indian Penal Code and the Criminal Procedure Code, and stands now reinforced by the modernised Disaster Management Act, 2005 (DMA). In a post-Covid-19 world, we may reflect on whether it was more of a catastrophe than a disaster and whether there should, indeed, be a multilateral treaty on the best ways to handle a pandemic.

The revival of powers conferred by a 123-year-old Indian Epidemics Act, 1897 (a law of only four sections, but vast in scope) is combined with the DMA. And the proclamation of a “notified disaster” signifies that states can make use of the State Disaster Relief Fund, while the central government contributes 55 percent for Union Territories (UTs) and over 90 percent for special category states/UTs (such as north-eastern states, Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand).

Moreover, as Ishan Bhatnagar and Ritesh Patnaik (two National Law University, Delhi students) have pointed out, the “prophetic” aspects of the Public Health (Prevention, Control and Management of Epidemics, Bio-Terrorism and Disasters) Bill of 2017 seem to have guided much of the anti-Covid-19 law and policy action today. Whether the continuation of colonial laws after 70 years of the working of the Constitution or whether the DMA provides ek dhakka aur do (give one more push) to the crumbling citadel of constitutional federalism should furnish some interesting post-Covid-19 concerns.

Yet, the constitutionality of certain offences under the Indian Penal Code is beyond doubt. These include Sections 188 (“disobedience to order duly promulgated by public servant”), 269 (“negligent act likely to spread infection of disease dangerous to life”) and 270 (“malignant act likely to spread infection of disease dangerous to life”). Much the same can be said of the rather elaborate seven sections of Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code which enable the executive to issue orders that prescribe powers to maintain order by taking extreme prohibitive actions that impinge variously on social and public life. However, Anuradha Bhasin (2020) now articulates the criteria of judicially reviewable objective satisfaction for Section 144 orders (see my article in India Legal on February 14, 2020).

In a deep constitutional irony, the Essential Commodities Act, 1955, a command and control planned national economy law, now helps, in a neoliberal era, to combat Covid-19! It enabled the Union government on March 13, 2020, to declare masks and hand sanitisers as essential commodities until June 30. This law’s vast potential to control production, supply and distribution and to secure their equitable distribution and availability at fair prices is once again writ large on the economy and the nation.

JUDICIAL APPROACHES

How should the justice delivery system efficiently function in a Covid-19 situation? The SC has boldly confronted this question (as per CJI SA Bobde, Dr Justice Dhananjaya Chandrachud and Justice Nageswara Rao) by invoking the powers of Article 142 and providing guidelines for court functioning (on April 6, 2020). The open embrace of digital and medical technologies is striking; had the Court accepted my suggestion in the early Bhopal days to establish a science and technology bench, a better access to a more thorough picture of the ongoing promise and peril of technologising the administration of justice, would have been possible. The SC had earlier decided (on March 23) that it would only convene benches to hear “extremely urgent matters”. The High Courts have also followed suit.

But the striking feature of the new normal is the wide exercise of suo motu jurisdiction. First, the SC has passed certain directions decongesting Indian prisons and remand homes and asked the states to prepare “readiness and response plans” for the prevention of the contagion. It has proceeded to enquire into the mid-day meal scheme (following the closure of schools and anganwadis across the country). Finally, the Court has directed that the time period for filing of cases before all courts/tribunals shall stand extended till such time that it passes further direction. There are instances where High Courts also have taken similar initiatives towards inclusive and complex equality. The SC is aware of the social criticism of the plight of migrant workers both within and across the states, (as late as April 6), it has declined to substitute the executive by judicial wisdom.

Covid-19 raises once again the issue of powers of nudge function. Social action litigation in India developed the art and science of the nudge function before a full-scale law and economics theory was built around it. A nudge is said to work independently of “forbidding or adding any rationally relevant choice options” and is also different from “changing incentives” (incentives that would also “modify rational behaviour”). Nudges, it is maintained, constitute a “genuinely distinct mode of governance, with a corresponding distinct normativity”. One may consider nudge functions “in a broader normative framework, along with other regulatory techniques; a broader project of good governance that is not distinct from law but encompasses various forms of legality” (see Péter Cserne, “Is Nudging Really Extra-legal?” 2016). Can socially responsible evaluation of judicial role afford to ignore the judicial nudge function at least in promoting incremental equality?

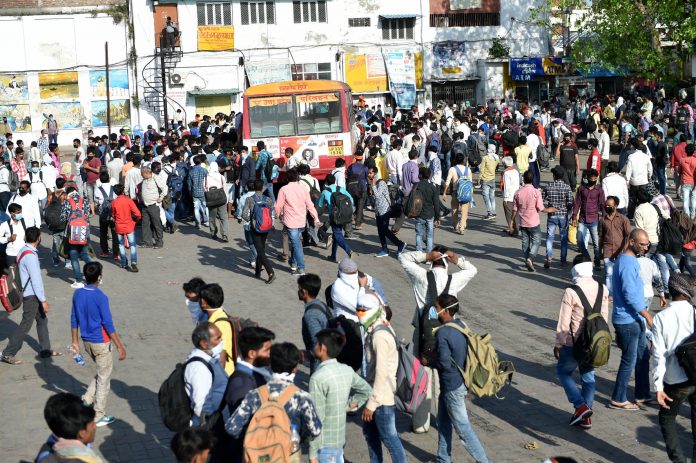

For example, performances of police brutality and even acts of sadism in dealing with citizen behaviour during the lockdown have marred the vaunted achievements of the lockdown regime. Pertinent questions have also been raised concerning acts of deprivation of dignity and health in the treatment of migrant exodus and at least in one instance, of mass spraying (Vrinda Grover et al: Bar & Bench, April 5, 2020). And the scope of violence by civil society actors, be it imminent food riots or domestic violence against women (see on the latter https://fightcovidnotpeople.in/2020/04/04/ensure- womens-rights-during-the-lockdown-an-open-letter-to-delhi-cm-kejriwal/) has been questioned. What constitutional courts can and should do to confront this remains a high priority matter for anxious debate and urgent social action.

However, the question what may constitute “urgent matters” has acutely arisen as the SC (per Nageswara Rao and Deepak Gupta JJ, April 3) has stayed the reasoned order of a single judge that matters of bail in SC/ST promotion were not urgent matters and these should not be listed because of Covid-19-related contagion. Similar was the effect of the orders of the Bombay High Court.

Are these foundationally “wholly illegal” as amounting to “judicial suspension of Article 21 rights” (as Dr Gautam Bhatia puts the matter)? Can these be further read as articulating the spirit of internal emergency imprinted on the Indian adjudicatory culture? Are these expressive of the “cavalier attitude towards the intersection of pandemics and mass incarceration”? Such questions raise all over again, the haunting qualities of fiat justitia and salus populi maxims in a Covid-19 world now infested with new summoning urgencies.

—The author is an internationally renowned law scholar, an acclaimed teacher and a well-known writer

Photo: UNI