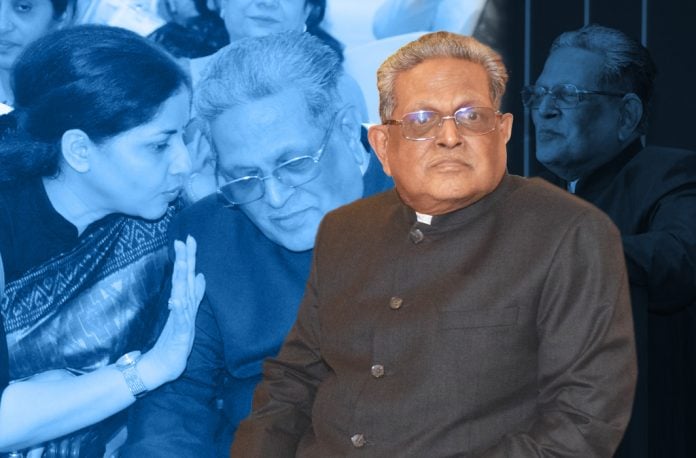

S RAJENDRA BABU was the 34th chief justice of India. He also served as chairperson of the National Human Rights Commission of India and was appointed a permanent judge of the Karnataka High Court in February 1988. He was elevated to the Supreme Court in 1997. In May 2004, as the most senior judge of the apex court, he succeeded Justice VN Khare as chief justice of India.

While his tenure at the top was comparatively short, as a Supreme Court judge, he delivered several landmark judgments on a broad range of issues—from constitutional matters to the environment and also corporate and taxation disputes. His most memorable judgment was his interpretation of mob psychology in the case relating to the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, following the assassination of then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. He also delivered a far-reaching interpretation on the provisions of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986.

Post retirement from the apex court, Justice Rajendra Babu was appointed the ICICI Chair (Professor) at the National Law School of India University. His abiding interest in community health led to him being appointed president of the International Nursing Services Association, a post he held for 25 years. In an interview with RAJSHRI RAI, MD, India Legal, and Editor-in-Chief, APN NEWS, he elaborated on contemporary concerns and his legal legacy. Excerpts:

As India and the world tackle the Covid-19 crisis, people of your calibre have a special role to play. You have been giving training in community health work as president of the International Nursing Services Association. Can you tell us about your experience in this field?

When I was practising as a lawyer I came in contact with some officers and workers from Oxfam—a well-known social service organisation. They, in consultation with administrators, heads of social organisations and doctors, who worked in CSI Hospital, Vellore, met at the instance of representatives of funding agencies. They formed the International Nursing Services Association, or INSA, as a registered society with small infrastructure to give advanced training to rural health workers. I was invited to head the executive committee.

The nature of the programme would not enable it to deal with a pandemic like Covid-19 except to bring awareness of the disease, personal protection, etc. In fact, such an exercise was done in relation to HIV, AIDS, TB, and use of tobacco, malnutrition, infant mortality, hygiene and similar matters. The funding was done mostly by approving programmes of their liking. By 2005, the funding was very heavily controlled by law and I could not spare much time for financial details as by then I was in the teaching faculty of NLSIU. Also, I was sounded about moving out of Bangalore; hence I resigned from the president’s post.

You have been the chairperson of NHRC. How do you draw a balance between protection of human rights and the need for the State to use police force to enforce lockdowns and quarantines?

NHRC is created by a statute for protection and promotion of human rights. No health protection duties were given to it; nor did I have any occasion to deal with any epidemic. I maintain a very low profile and I am not in public life or work as a social activist. The experience either at NHRC or INSA will not help me in the present situation.

What advice would you have for governments in dealing with the needs of health workers, especially during an epidemic? Have we learnt any lessons?

The pandemic we are facing has two aspects—public health and personal health. If personal health is properly taken care of, public health issues will not arise at all except perhaps from spreading to others. If everyone is careful, such a situation may not arise. However, on the basis that it is highly contagious, the government may like to take certain steps. Even if extensive testing is done, there being no cure, the only result is isolation. Isolation leads to psychological problems.

In the three speeches made by the prime minister, all that was stated was what we have to do during the lockdown period. Nothing was elucidated as to the steps to be taken by his government.

In our country we do not have social security measures at all. With complete lockdown, no agricultural, commercial or industrial activities can be carried on and the labour class dependent on them will have no wherewithal to live on. They will have to seek shelter and alms for food. Lockdown has been imposed with no vision as to social or economic cost. I need not elaborate on these aspects as very good informative discussion is available in the media. In any emergency, the liberties of citizens can only be reasonably restricted and not trampled.

As India’s 34th chief justice and as a judge of the Karnataka High Court, you delivered landmark judgments in civil, criminal, environmental, constitutional, taxation, corporate and IPR cases. If you were to choose the most challenging subject among these, which would it be and why?

I have discharged my functions as a judge to the best of my ability after interaction with stalwarts in the profession. I could retire with complete job satisfaction. The gap between law and justice must be bridged and law must be interpreted to render justice; for, courts are not courts of law but of justice. This is the real challenge for a judge.

In an important case, the Supreme Court ruled that the Tandava Nritya (dance) in public with skull and trishul was not part of the Ananda Marga faith. Can you elaborate on this?

Ananda Margis wanted to perform tandava dance by holding a skull and a live snake while receiving their religious leader at airports or railway stations. In an earlier case, the Court held that this ritual was not part of their faith. Later on, this ritual was sought to be added by rewriting their faith which we held was not permissible and also such ritual was not an essential part of their religion.

You analysed provisions of the Muslim Women Act of 1986 in Daniel Latifi vs Union of India.

In Daniel Latifi’s case, the issue was related to payment of maintenance to a divorced wife which was upheld in the Shah Bano case. The validity of the new law to overcome this decision was questioned before us.

We held that by a practical interpretation of the new law, divorce will not be effective unless adequate provision is made for the upkeep and maintenance of the wife without going into the constitutional aspect. We felt that the object of modifying the law had misfired. Incidentally, we examined the condition of women in India.

In today’s India, sale of PSUs is a big controversy and debate. You passed many judgments, including disinvestment of government equity in HPCL and BPCL, after your elevation to the Supreme Court in September 1997. What are your thoughts on these matters now? Should the courts be involved in the issue?

We have to recall the history behind the law for acquisition of petroleum companies which were in the private sector. It was said that petroleum products are highly sensitive to defence and security of the state. After acquisition, PSUs thrived and became profit-earning companies. The government thought they could reduce their equity and allow privatisation.

We held that acquisition was made under a law and therefore privatisation should also be under a law. If any infrastructure is brought into existence by using government funds, it can be dismantled only by an appropriation act. No safeguards were provided to keep control of the company. So, we held that disinvestment was not permissible.

You can be quite harsh and outspoken in your judgments. In 2002, in Natarajan vs Subba Rao, you came down severely on the designated judge for “crippling” the freedom of a prosecutor. What was the main principle involved?

In Natarajan vs Subba Rao, the complaint was that the attorney general had given an opinion mala fide and in a biased manner. We held such an attitude cannot be attributed to him and in that context we might have made some observations.

You have also been an educationist as Chair (Professor), NLU. In your LLB in 1939, you stood first class first. What do you think of legal education in India today? Where does it need the most improvement? Are we becoming just degree factories?

My speeches on legal education, rights regarding life, liberty, equality, human dignity, women’s rights, independence, accountability of judiciary are all in the public domain and easily accessible. I need not reiterate them.

You have a great interest in Vedic learning and Vedanta. What is the greatest lesson you have learned from the Upanishads that you would like to share with us? I believe that contentment is the true happiness in life which leads to non-attachment or vairagya. Vairagya is the essence of Vedanta. Music is performed in the background of shruti. Without shruti, no music concert can be held but shruti does not interfere with music. That’s how Vedanta will be in the background of life.