Though the Kulbhushan Jadhav case has been propelled to the international stage and India has won the first round, there is uncertainty over whether Pakistan will listen to The Hague or its own judges

~By Parsa Venkateshwar Rao Jr

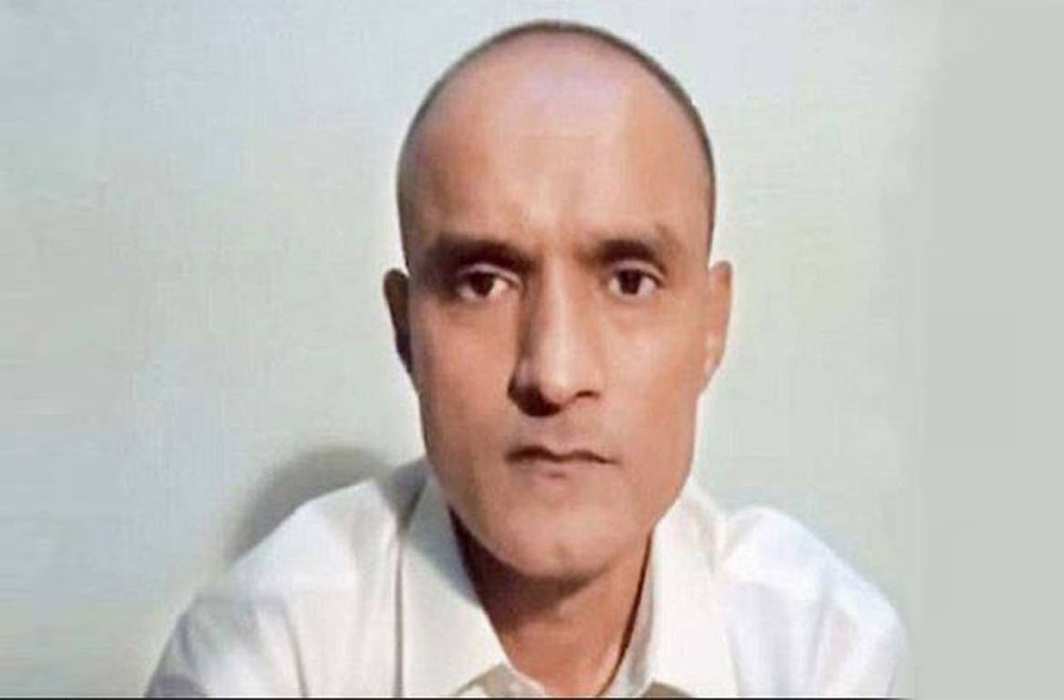

This is not a cricket match where screaming fans can egg on their side. An individual’s life and the rights of two sovereign states are at stake. So the order of the International Court of Justice at The Hague on May 18 asking Pakistan not to execute Kulbhushan Sudhir Jadhav, a former Indian Navy commander accused of espionage and terrorism and sentenced to death by a General Court Martial, should be seen as a legal relief. The legal battle has not even begun. So far, India has won a reprieve.

Pakistan stands firm in its view that Jadhav is an Indian spy sent into the country to unleash terrorism, and that sentencing him is part of its righteous war against terrorism. It is no use getting angry with Pakistan’s arguments which form part of its rhetoric, mainly political and partly legal. India has no option but to deal with Pakistan, whether at the negotiating table during bilateral talks or at international forums such as the ICJ and the United Nations. India had decided to fight the legal battle over Jadhav. And it involves finer points of international law.

In its application, India cited Article 36 (b) of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations 1963 and Article I of the Optional Protocol. Article 36 mandates consular access to nationals of the country represented by the diplomatic mission. And Article I of the Optional Protocol says: “Disputes arising out of the interpretation or application of the Convention shall lie within the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and may accordingly be brought before the Court by an application made by any party to the dispute being a Party to the present Protocol.”

The ICJ, in its order, has accepted India’s contention on these two issues. It has accepted that the dispute over consular access needs to be addressed, and that the issue falls squarely within the jurisdiction of the Court.

India has, however, taken a maximalist position. In its application, it has asked the Court to suspend the death sentence against Jadhav, to restrain Pakistan from executing him and to “annul the decision of the military court”. It has pleaded that if Pakistan is unable to set aside the death sentence, then the ICJ “must declare the decision illegal” and direct it “to release the convicted Indian National forthwith”.

India has, however, taken a maximalist position. In its application, it has asked the Court to suspend the death sentence against Jadhav, to restrain Pakistan from executing him and to “annul the decision of the military court”. It has pleaded that if Pakistan is unable to set aside the death sentence, then the ICJ “must declare the decision illegal” and direct it “to release the convicted Indian National forthwith”.

India requested immediate measures “pending final judgment in this case” to “take all measures necessary to ensure that Mr Kulbhushan Sudhir Jadhav is not executed”, that Pakistan inform the ICJ about the action it has taken to defer the execution and that nothing is done to “prejudice the rights” of India and Jadhav. India requested that given “the extreme gravity and urgency of the threat”—of Jadhav being executed—the Court “render an Order on its Request without a hearing”.

It can be seen that the Court has acceded to India’s request for the provisional measures, but it did not agree to give the Order without hearing the other side. “The Court decided to hold a hearing in order to allow both Parties to present their arguments.” (Verbatim Record of the proceedings).

Harish Salve, India’s counsel, carefully argued the issue of Article 36, paragraph 1 of the Vienna Convention on Consular Access and cited the decision of the Court in two earlier cases. These were the LaGrand case (between Federal Republic of Germany and the United States of America, 1999) and the Avena case (between Mexico and the United States, 2003). In both, the ICJ had ruled in favour of Article 36 of the Vienna Convention and the Federal Republic of Germany and Mexico. Salve argued: “The graver the charges the greater the need for punctilious adherence to the Convention.”

The Pakistan side had used rhetorical language interspersed with legalities to make its point. Dr Mohammad Faisal, Director-General (South Asia and SAARC), said that Pakistan was “being ambushed into appearing before the Court on a few days’ notice, and we are here”. And again towards the end of his presentation, he said: “Whilst we were bounced into appearing before the Court, it is always an honour to do so.” And at another point, he said: “More importantly, if the Court will forgive my language, we simply have no reason to stop the canary from singing. Others might wish that, we do not.”

The other point Faisal made was there was enough scope for Jadhav to pursue appeal. He said: “Pursuant to Article 184-3 and Article 199 of the Constitution of Pakistan, individuals have successfully obtained relief from the courts. India and Pakistan have a common source for the vast bulk of our legal processes and procedures.”

He also said:“Just to make the point absolutely clear, an expedited hearing which would dispel any suggestion for the need of provisional measures is an approach that Pakistan would invite the Court to adopt. On this basis, Pakistan would be content for the Court to list the Application of India for hearing within six weeks.”

The counsel for Pakistan, Khawar Qureshi, QC (Queen’s Counsel), said India’s plea for provisional measures was based on “bootstraps arguments”. And he went on to explain: “If there is no availability of substantive relief, provisional measures cannot and should not flow. A bootsraps argument is a term familiar to English lawyers, and I apologise for using it, but I hope one can visualise how someone is trying to pull themselves up from their boots.”

On the legal front, Pakistan has sought to corner India on the issue of Jadhav’s passport. Its argument is that if Jadhav is an Indian national, as claimed, then his true passport has to be presented and not the “false” one he had at the time he was arrested where his name was shown as Hussein Mubarak Patel.

On the issue of consular access, it has tied itself up in knots. First, the argument was that neither the Vienna Convention nor the 2008 bilateral agreement between India and Pakistan over consular access extends to spies and terrorists. This was based on its contention that Jadhav was a spy and a terrorist. On the other hand, it denied that it did not allow consular access, and argued that it sought India’s help for evidence in the case and was willing to consider the issue of access. It said there was a time-bound obligation for this.

What can be asked is whether Pakistan has any other corroborative evidence to prove Jadhav’s alleged acts of subversion other than his confessional video. But that issue, it will be said, will have to be argued in Pakistan courts and it will have to be decided by their judges, and there is not much that the ICJ can do about it.

Qureshi said: “It was not that long ago that the Soviet Union and the United States of America were engaged in what is known as the Cold War, and we all accepted the fiction that there were no spies.”

Is it time then to recognise spies and accept that they have rights though they may not be extended diplomatic immunity? But then, no state will ever own up a spy, and it will be no different with India and Pakistan.

The case then hangs in the balance.