The landmark judgement has opened the doors for blocking defunct personal records from free public access on the Internet

~By Ajith Pillai

In this age of internet and search engines there may be records from your past which have no relevance to your present or future life. For example, there might be civil cases which have been closed, disputes which have been amicably settled and dusted. But they reappear each time your name is searched. These defunct documents, if kept alive in the public domain, may prove to be nothing more than a source of embarrassment. Do you have the right to have irrelevant documentation blocked? Or simply put: Do you have the right to be forgotten?

EXPOSED BEYOND COMFORT

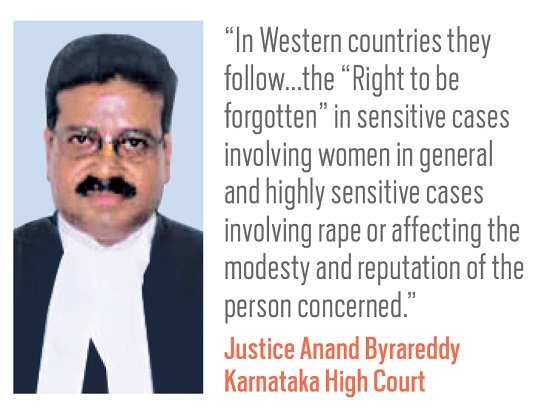

Indian law does not provide citizens any such right. In fact, the Information Technology (IT) Act, 2002 and the IT Rules, 2011 do not even delve on the issue. And yet, in a landmark judgement last month, Justice Anand Byrareddy of the Karnataka High Court adjudicated in favour of the right to be forgotten. This is the first time that an Indian court has taken cognisance of what is enshrined in the European Union Data Protection Directive, 1995 which gave citizens of member states the right to block defunct personal records.

The case which came up before the Karnataka High Court needs recounting to place the judgement in context.

A woman (Ms X) had filed a criminal complaint resulting in an FIR being lodged against her “husband” under various sections of the IPC. She also filed a civil suit seeking declaration that there was no marriage between her and the man and prayed for the annulment of the marriage certificate that was issued to the couple.

A woman (Ms X) had filed a criminal complaint resulting in an FIR being lodged against her “husband” under various sections of the IPC. She also filed a civil suit seeking declaration that there was no marriage between her and the man and prayed for the annulment of the marriage certificate that was issued to the couple.

However, a compromise was reached between them and their families. It was agreed upon that Ms X would withdraw her original criminal complaint and terminate all legal procedures initiated by her and continue with the marriage. A petition was filed by the husband to quash the case against him and the prayer for withdrawal was granted through a court order.

Subsequently, Ms X’s father approached the Karnataka High Court with the plea that his daughter’s name and address should be blocked from the court order relating to the quashing of the case against her husband which was in the public domain. In his ruling Justice Byrareddy put on record the family’s fears: “It is the apprehension of the petitioner’s daughter that if a name-wise search is carried on by any person through any of the internet service providers such as Google and Yahoo, this order may reflect in the results of such a search and therefore, it is the grave apprehension of the petitioner’s daughter that if her name should be reflected in such a search by chance on the public domain, it would have repercussions even affecting the relationship with her husband and her reputation that she has in the society and therefore is before this court with a special request that the Registry be directed to mask her name in the cause-title of the order passed in the petition filed by her husband—accused in Criminal Petition No.1599/2015, disposed of on June 15, 2015.

Further, if her name is reflected anywhere in the body of the order apart from the cause-title, the Registry shall take steps to mask her name before releasing the order for the benefit of any such other service provider who may seek a copy of the orders of this court.”

The court directed that it “should be the endeavour of the Registry to ensure that any internet search made in the public domain ought not to reflect the petitioner’s daughter’s name…”

Justice Byrareddy concluded his judgement by spelling out why he had recognised the right to be forgotten. To quote: “This would be in line with the trend in the Western countries where they follow as a matter of rule the “Right to be forgotten” in sensitive cases involving women in general and highly sensitive cases involving rape or affecting the modesty and reputation of the person concerned. The petition is disposed of accordingly.”

However, the Karnataka High Court ruling makes it clear that a wiping out of the woman’s name from all official court records is not feasible. It notes “if a certified copy of the order is applied for, the name of the petitioner’s daughter would certainly be reflected in the copy of the order.”

DEMANDING AMNESIA

While addressing the issue of public access to personal data, the High Court was touching upon a matter of universal concern. Websites and courts the world over are being flooded with requests to be forgotten. According to Google’s Transparency Report 2016, last year the website received 565,412 requests to delete URLs. It acted by deleting 43.2 percent of them. The volume of requests, the report points out, will only increase in the future.

There is case pending in the Delhi High Court where a petitioner has prayed that he is being denied jobs because his wife and his mother-in-law’s names figure in a criminal case. His contention is that when his name is searched on the internet by prospective employers the objectionable case and court orders pertaining to it pops up. The court is yet to adjudicate in the matter.

In another case, the Gujarat High Court dismissed the petition in which the petitioner had sought the court’s direction to restrain Google and the website Indiankanoon.org from publishing the judgment of a case in which he had got an acquittal. The court ruled that the judgment posted on the net was pronounced by the court and publishing it could not be restrained by and legal provisions.

The Karnataka High Court judgement has addressed a critical issue of immense contemporary relevance which has so far not been addressed by Indian laws. The right to be forgotten, no doubt, is a complex issue that involves personal privacy and the public’s right to information. Perhaps the judgement will inspire our lawmakers to bring clarity into the IT Act on an issue that needs to be urgently addressed.