Pending litigation between various government departments has shot up to over a lakh cases and there seems little hope of succour, leading to a huge backlog and loss to the exchequer

~By Parsa Venkateshwar Rao Jr

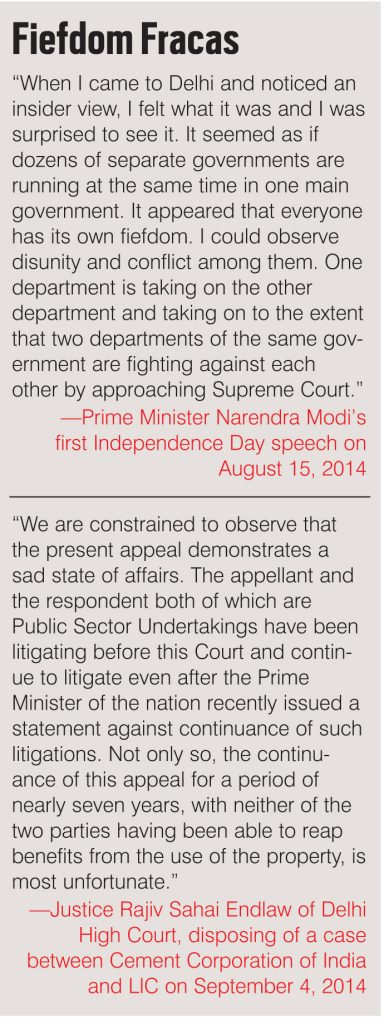

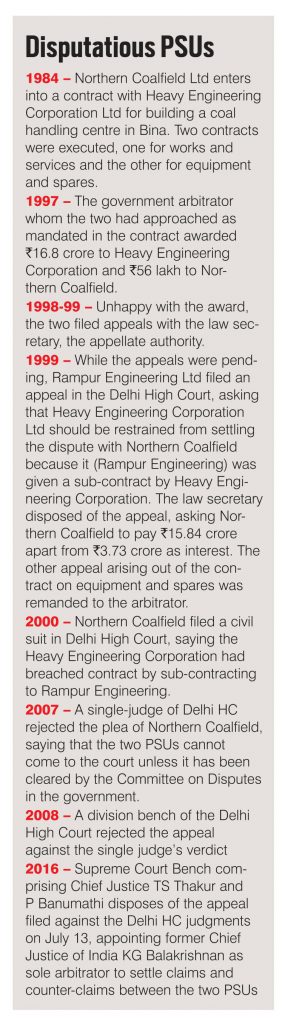

In the three-decade-old case of Northern Coalfields Ltd (NCL) v Heavy Engineering Corporation Ltd (HECL), former Chief Justice of India TS Thakur and Justice P Banumathi appointed former CJI KG Balakrishan as the sole arbitrator. This decision on July 13, 2016, raised many eyebrows. A senior official of the Ministry of Law and Justice, speaking on condition of anonymity, said that the apex court was wrong.

Speaking to India Legal from the headquarters of Heavy Engineering Corporation in Ranchi, its senior law officer Amit Srivastava said that Justice Thakur had appointed the sole arbitrator after the two PSUs (see box) appealed against the decision of the Permanent Machinery of Arbitration (PMA) in the Department of Public Enterprises (DPE). He said the proceedings had not yet been concluded and what the apex court said was the law of the land.

Meanwhile, Delhi High Court’s acting Chief Justice Gita Mittal was sharply critical of the lingering case between these two Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) which turned up like a bad penny on June 7. One of the contestants had filed for a refund of court fees to the tune of Rs 65 lakh which had been deposited with it since 2000. The Court made the Delhi government a party to the case and also ordered for an assessment of the time and resources expended by it in dealing with these two litigious PSUs.

The Delhi High Court made a sharp observation: “Public money is being expended in prosecution and defence of the cases… we have no information of the litigation expenses already incurred by both sides which includes lawyers’ fees and expenses. Such litigation which is almost between two limbs of one ‘body’ (government) is a gross wastage of public money.”

The legal dispute between these two PSUs is the proverbial tip of the iceberg. There are other PSU litigations which are pending and which take the shape of either a dispute between two PSUs or a PSU and a government department. However, there is no count of the exact number of cases pending before courts involving PSUs.

However, the PMA Cell shows that 66 cases were pending on April 1, 2017, nine have been disposed off in 2016-17, six in 2016 and three this year. There is the curious list of 22 cases which have been adjourned sine die, that is, no date has been fixed for the next hearing. Of these, seven have been adjourned on January 18 this year, and six date back to 1999 and one to 2003. Nine of them were last heard in 2008. It is obvious that the record on the arbitration front in the government is dismal. The pending cases involving PSUs remain baffling. After attempts of successive governments to rein in PSUs from getting into endless legal battles, there is still no light at the end of tunnel.

However, the PMA Cell shows that 66 cases were pending on April 1, 2017, nine have been disposed off in 2016-17, six in 2016 and three this year. There is the curious list of 22 cases which have been adjourned sine die, that is, no date has been fixed for the next hearing. Of these, seven have been adjourned on January 18 this year, and six date back to 1999 and one to 2003. Nine of them were last heard in 2008. It is obvious that the record on the arbitration front in the government is dismal. The pending cases involving PSUs remain baffling. After attempts of successive governments to rein in PSUs from getting into endless legal battles, there is still no light at the end of tunnel.

In 2011, there was a famous case in the Supreme Court involving the Electronics Corporation of India, which falls under the Department of Atomic Energy, and the Commissioner of Central Excise (Ministry of Finance). Successive governments have been aware of the problem of PSU litigation which has been going on for decades now.

It was in 1988 that the 126th Law Commission Report dealt with the thorny issue of litigation involving PSUs under the title: “Government and Public Sector Undertaking Litigation Policy and Strategies”. Rajiv Gandhi was then the prime minister and there was a glimmer of economic liberalisation on the horizon. The burden of the report was clear: To dissuade PSUs from entering into endless legal wrangles with each other.

Cut to 2010 when Law Minister Veerappa Moily announced the National Litigation Policy, where one of the thrust areas was how to deal with PSU litigation. This litigation not only increased pendency of cases but also created the sorry spectacle of one PSU pitted against the other, both of which were created by the central and state governments and sometimes through an act of parliament or state legislatures.

In 2015, then Minister for Law and Justice Sadananda Gowda announced a review of the National Litigation Policy of 2010. A law ministry official said: “The review became necessary because the 2010 National Litigation Policy could not be implemented.” But the review has not yet been done. “It is under preparation,” is all that officials in the ministry say.

The ministry is engaged in making a statistical table of pending litigation involving the government, and that includes PSUs. More than a lakh of cases have now been tabulated and the work is not complete. Sources said that this data is not available to the public and is meant as a reference for different ministries and departments in the government.

But PSU litigation is not the sole focus of the National Litigation Policy. Its thrust is on the government as a litigant, and there is general recognition, especially in the Supreme Court, that government is a “compulsive litigant” and the mountain of pending cases is largely due to it. The Litigation Policy of 2010, as well as its 2015 review, deals with this problem.

The parliament and the government have been grappling with the issue of PSU litigation in their own way. This has ranged from suggestions in the 154th Public Accounts Committee (PAC) report in 1974-75 to the office memo issued by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) in July 2014 asking PSUs to desist from going to courts and initiating litigation. But no one in the government seems to know whether these directions have been implemented and whether litigation involving PSUs has come down.

There have, however, been a series of office memos after the Supreme Court on February 17, 2011, rescinded its October 11, 1991 directive that a PSU cannot file a case until it is cleared by a Committee on Disputes (CoD) in the Cabinet Secretariat. The Cabinet Secretariat through its note of September 1, 2011 acknowledged the Supreme Court order and declared that “the Committee accordingly stands wound up with effect from the same date (February 17, 2011)”.

However, a system of consultation was revived informally by the PMO immediately after Narendra Modi took over in May, 2014. In a circular on August 7, 2014, PK Malhotra, secretary in the Ministry of Law and Justice informed secretaries of all departments: “In a meeting chaired by Principal Secretary to the Hon’ble Prime Minister on 31 July 2014 the issue relating to instructions to all the Ministries/ Departments/PSUs/Boards/Authorities under administrative control of various Ministries/Departments to desist from initiating inter-ministerial /departmental litigation in the Court of Law was discussed.”

It took note of the fact that “…a Permanent Machinery of Arbitration is functioning in the Department of Public Enterprises….” In case it was not possible to settle differences and disputes, the circular says “…the same should be referred to the Cabinet Secretariat and, then, if necessary to PMO”.

It took note of the fact that “…a Permanent Machinery of Arbitration is functioning in the Department of Public Enterprises….” In case it was not possible to settle differences and disputes, the circular says “…the same should be referred to the Cabinet Secretariat and, then, if necessary to PMO”.

There is however a constitutional twist to the story—should PSUs be considered state entities. The 145th Law Commission Report of 1992 under the heading “Article 12 of the Constitution and Public Sector Undertakings” dealt with the question of whether PSUs fall in the ambit of Article 12 of the Constitution, and whether removing them from the ambit of this Article through the proposed amendment would help reduce litigation. The commission said that complete judicial non-interference cannot be established.

Supreme Court Justices Syed Shah Quadri and Ashok Bhan in their judgment of February 18, 2003 in Chief Conservator of Forests, Govt. of A.P. v Collector and Others observed: “Under the scheme of the Constitution, Article 131 confers original jurisdiction on the Supreme Court in regard to a dispute between two States of the Union of India or between one or more States and the Union of India. It was not contemplated by the framers of the Constitution or CPC (Civil Procedure Code) that two departments of a State or the Union of India will fight litigation in the court of law.”

Additional Solicitor General PS Narasimha offers a counter-argument. He says if PSUs were established as autonomous corporations for commercial purposes, it is unfair to ask them to conform to rules and norms of a government department. If a PSU is expected to make profits, then it should be able to guard its commercial interests, if need be by turning to the courts.

There is a clear recognition in the Ministry of Law and Justice that PSU litigation, be it fighting private parties or with each other, persist. And despite the efforts of successive governments, including Modi’s, to contain PSU litigation, there has been little impact.

The ministry’s own initiative of settling inter-PSU cases through arbitration outside of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act has had only modest success till date.