Three-year-old Sherin Mathews’ tragic end in the US started in a heartless adoption procedure back home

~By Sujit Bhar

The tragic and confusing death of the three-year-old Indian girl, Sherin Mathews (Saraswati in India), in Richardson town, Texas, US, in the care of her adoptive American parents, Wesley and Sini Mathews, has become more mysterious.

Many versions of the story have appeared in the media, but when India Legal investigated the issue, it found while the case is yet to be solved in the US, many pieces of the jigsaw puzzle were not fitting back home in India either.

The adoption process in India, especially for inter-country adoption, is pretty rigorous, at least on paper. This may be a one-off case of such adoption gone haywire, but the tragedy has made it imperative to probe the issue.

Starting from the basics, one has to understand how inter-country adoption takes place and how it happened for the Wesley couple.

First, details of a “legally free” (box on facing page) child are put up on the relevant website of the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA). That is where foreign couples get to see the child first.

The details of the child are accompanied by his/her health report. Sherin was a special needs child. Originally, only special needs children were available for international adoption, points out Shireen Merchant, a lawyer dealing with adoption, but a recent change in the rules says if a child is rejected three times within the country, he/she can be put up for international adoption.

According to Babita Kumari (see interview), who ran the adoption agency, Nalanda Mother Teresa Anaath Seva Ashram, from where Sherin was selected, the Mathewses approached one of CARA’s Authorised Foreign Adoption Agencies (AFAA). CARA has clearly laid out the functions of an AFAA. Out of the eight instructions for AFAAs in the CARA notification, No 3 clearly says: “Give orientation to the prospective adoptive parents on culture, language and food of the place to which the adopted child belongs.”

How does a child become “legally free”?

For any adoption, first the child has to be declared “legally free” for adoption. There is a set process for this.

For any adoption, first the child has to be declared “legally free” for adoption. There is a set process for this.

When an orphan child is set up for adoption, as per the Juvenile Justice Care and Protection of Children Act, all documents pertaining to the child are examined to see if she has any roots. Reviews conducted by adoption agencies are supposed to be overseen by the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA), the nodal agency within the Ministry for Women and Child Development. If the child has parents who want to give up their child for adoption, papers are drawn up and gone through court procedures to ensure that the parents have surrendered all their rights over the child. Only then can the adoption process start.

While it is good on paper, it is clear from a discussion with Babita that many of these details remain on paper. Wesley came to India and to the adoption agency to select the child. He hails from Kerala, though he is a Qatari by birth, while his wife, Sini, was born in the UAE. They are both US citizens.

“Sini had not come for the first visit, because she is a teacher and did not get leave,” Babita told India Legal. “When Wesley selected Saraswati, he called up Sini and they had a talk over the phone and decided. Sini came later, when the final signatures had to be put and the adoption process had to be completed.”

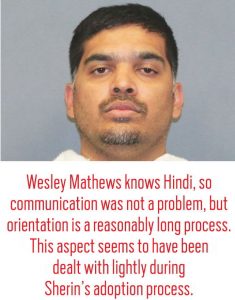

How was directive No. 3 dealing with orientation completed? According to Babita: “There was a gathering of children at the centre where the parents were treated to some fun and games and food.” That was it. Wesley knows Hindi, so communication was not a problem, but orientation is a longer process. Under no circumstances can what happened be called an “orientation”. Did Saraswati get to like Wesley? Did her choice matter?Answers to these questions are awaited.

What Indian authorities insisted upon was a strict adherence to written documentation. However, a child has his or her unique needs, and these must be looked into.

Speaking to India Legal, Lt Col Deepak Kumar, CEO of CARA, made it clear that CARA cannot be faulted in its dealing with inter-country adoptions. “CARA last year (till March) went through 600 inter-country adoptions (of a total of 4,000), and I have handled 200 of them,” he said. “There has been no problem so far. This is a one-off case. Let me tell you, CARA is an extremely careful and responsible organisation.”

He talked about how “trained social workers in the US”—organised by Holt International—had visited the house of the Mathewses and had checked on Sherin. “I have 40 pages of reports to show that things were fine. There were five reports,” he said.

“They had given good reports of progress from Richardson regarding Sherin,” he said. “These reports are mandatory and we keep a close watch.”

So what happened? There are two worrying areas. First, while the reports talked about good “adjustment”, they also mentioned that Sherin was having eating problems, not wanting to eat at home, but outside. That problem seemed to have grown and it was never mentioned in detail how this was being dealt with.

Bitter end to adoption

A look at how the Sherin Mathews tragedy unfolded

On July 8, 2016, a chirpy three-year-old girl, Saraswati, originally given up by her biological parents in Gaya, was adopted in Nalanda by an Indian-American couple, Wesley and Sini Mathews. The happy girl, with a slight squint in one eye, went all the way to Richardson, a town in the suburbs of Dallas, and was renamed Sherin. But on October 7, 2017, Sherin went missing. The police searched high and low with a large number of personnel and even with helicopters and drones. On October 22, Sherin’s body was found by police dogs under a culvert, one km from her house.

On July 8, 2016, a chirpy three-year-old girl, Saraswati, originally given up by her biological parents in Gaya, was adopted in Nalanda by an Indian-American couple, Wesley and Sini Mathews. The happy girl, with a slight squint in one eye, went all the way to Richardson, a town in the suburbs of Dallas, and was renamed Sherin. But on October 7, 2017, Sherin went missing. The police searched high and low with a large number of personnel and even with helicopters and drones. On October 22, Sherin’s body was found by police dogs under a culvert, one km from her house.

The mystery around the death was compounded when Wesley gave conflicting reports to the police regarding how the girl managed to go so far from her house at a late hour. Different versions of the couple having ordered her to drink milk and when she refused, of having ordered her out of the house, have emerged. The police have refused to accept the parents’ version.

Richardson police re-arrested Wesley, 37, on October 30, charging him with first-degree felony of injury to a child and for trying to confuse the investigation with conflicting statements given to the police. Wesley had earlier been arrested for suspected child endangerment for the ill-treatment of his adoptive daughter. He was released on bond.

The tragedy has had repercussions in India. External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj has requested her cabinet colleague, Women and Child Development Minister Maneka Gandhi, to probe the adoption process, especially in inter-country adoption cases. Swaraj has requested Gandhi to institute tighter checks while issuing passports for adopted children. It has been decided that no such permission will be given without the consent of the ministry.

The other clue could lie in the abrupt shutting down of Babita’s adoption agency by the authorities through a letter dated September 7, 2017. The shutters came down on September 15 and the children in the agency were transferred to another agency.

The reason given was “irregularities” and that the agency was not being run as per norms. The last three times investigators had visited the agency were on December 8, 2016, May 15, 2017 and June 2, 2017. While the letter to Babita says that the reports were all negative, Babita told India Legal that no investigator had ever turned up and that “none of the supposed reports that the investigators had submitted to their superiors bore any signature of either the social worker present here or of the coordinator.”

The reason given was “irregularities” and that the agency was not being run as per norms. The last three times investigators had visited the agency were on December 8, 2016, May 15, 2017 and June 2, 2017. While the letter to Babita says that the reports were all negative, Babita told India Legal that no investigator had ever turned up and that “none of the supposed reports that the investigators had submitted to their superiors bore any signature of either the social worker present here or of the coordinator.”

It has to be remembered that the adoption process of Sherin had been completed at the agency barely five months before the investigators “arrived” and gave negative reports, resulting in the shutdown.

Even if one accepts that what Babita claimed to this correspondent wasn’t probably the entire truth, it becomes clear that the government, all the way up to CARA, was well aware that something wasn’t right in the procedures followed. The logical step would have been to immediately review the adoption processes already gone through, of which Sherin was also a part.

Even if one accepts that what Babita claimed to this correspondent wasn’t probably the entire truth, it becomes clear that the government, all the way up to CARA, was well aware that something wasn’t right in the procedures followed. The logical step would have been to immediately review the adoption processes already gone through, of which Sherin was also a part.

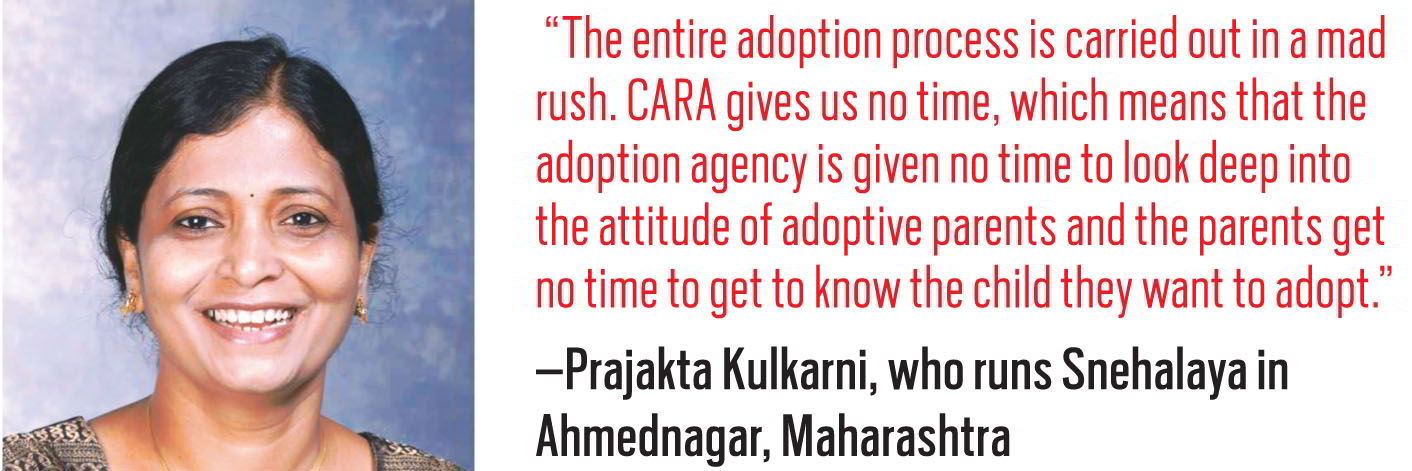

Prajakta Kulkarni, who runs an adoption agency, Snehalaya, in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, and is aware of the rules regarding inter-country and intra-country adoptions, told India Legal: “The entire adoption process is carried out in a mad rush. CARA gives us no time, which means that the adoption agency is given no time to look deep into the attitude of adoptive parents and the parents get no time to get to know the child they want to adopt. More importantly, the poor child gets no time to adjust to strangers —especially if they are white—suddenly becoming his or her parents.”

“The problem arises with the speed of the adoption process”

IL gets the legal perspective from advocate Shireen Merchant

Shireen Merchant, a lawyer dealing with adoption, including inter-country cases, says that things started getting worse after the online process was started two years back. “There used to be time earlier for the parents to meet the child and get to know each other, and a certain bond would develop before they actually adopted the child,” she says. “The problem arose when certain adoption agencies started asking for donations and pressured parents for money. When the parents complained, the government—India is a signatory to the Hague Adoption Convention—switched to the online method. The intention was noble, but the inherent problems have not been looked into.” Now an agency gets Rs 40,000 for an in-country adoption (including legal fees) and $5,000 for an inter-country adoption.

Two things stand out like sore thumbs, she says. “First is the speed at which the entire process is carried out,” says Merchant. “That is not fair to any party. Secondly, it would be wise for the parents to meet the child first. In an inter-country adoption, this meeting is not even mandatory. I have seen cases, in domestic adoptions, where parents who have suddenly decided not to keep the child any more come back to the agency to dump the child. There are legal implications, but at least the child has a place to stay.”

What if this happens abroad, when the child has already been granted citizenship of that country? Governments around the world issue citizenship immediately after receipt of CARA’s Certificate of Conformity of Adoption.

What is this hurry like? When the parents apply, they wait for a “free” child to be allotted to them for their perusal. Over e-mail, they get a child study report, photograph (pictures of three children are sent) and health certificate. For domestic adoptions, the parents get just 48 hours to decide (and they haven’t even met the child) and for inter-country, 96 hours.

If they refuse a child, they go straight to the bottom of the waiting list. How long is the waiting list? According to Kulkarni, there is a waiting list of approximately 17,000 parents and very few “free” children up for adoption.

Then the CARA documentation starts. For foreigners, there is a window of one month for their dossier of relevant information to come to CARA.

“The agencies are pressured, the parents are pressured, and the child is pressured no end,” says Kulkarni. From what Kulkarni described, it seemed more like a deal in commodities. Merchant describes it more aptly like an online shopping mall with the clock ticking—rather than the transfer of a child with a soul and feelings, from one country to another, from one culture to another and from one home to a strange place that he/she must call home.

Sherin was a victim of all this and her glass of milk was no more than a window to her lonely soul.

“Sherin never had a problem with drinking milk”

Babita Kumari of Nalanda Mother Teresa Anaath Seva Ashram talks to IL:

Babita Kumari’s Nalanda Mother Teresa Anaath Seva Ashram was ordered to shut down on September 7, 2017. Sherin was selected by the Mathewses from this Ashram. Babita talks about Sherin: “Look at Sherin’s picture. Do you feel in any way that she was depressed or uncared for or undernourished? She was a jolly girl in my adoption agency. She had been drinking milk for a long time. Every morning, around 6-7 am, all children drink milk. When the children are small, they drink from a bottle and later they are shifted to drinking from glasses. Not one of the ayahs ever complained to me that she was not having milk. And there was no question of choking on her milk. Her only ‘defect’, if you can call it that, was that she had a minor squint in one eye, effectively making one eye become smaller sometimes. She was a perfectly healthy child with me.”

She talked about the procedures followed at her Ashram. Adoption, especially inter-country adoption, has to go through several strict forms as prescribed in the Juvenile Justice Care and Protection of Children Act. The prospective parents in inter-country adoption are probed deeply, and a Home Study Report (HSR) is prepared. This HSR looks into the prospective parents’ passport and visa details, their educational and professional qualifications, details of their property, and many other angles, including police verification. Thereafter, a dossier is prepared and copies of it are sent to CARA, the district judge of Nalanda and other places, while one is kept with the adoption agency.

“Saraswati stayed in my adoption agency for 16 months, and there was no problem,” she says. “No child had ever had any problem, yet they shut down my Ashram,” she added.