The testimony of a 12-year-old boy who saw his father being murdered by killers hired by his mother was accepted as “reliable” by a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court

~By India Legal Bureau

If a 12-year-old is the solitary witness to his father’s murder, should his testimony be considered credible enough to warrant the conviction of the two hired killers? And if his mother was the one who plotted the killing, should the son’s testimony be enough to sentence her to life imprisonment?

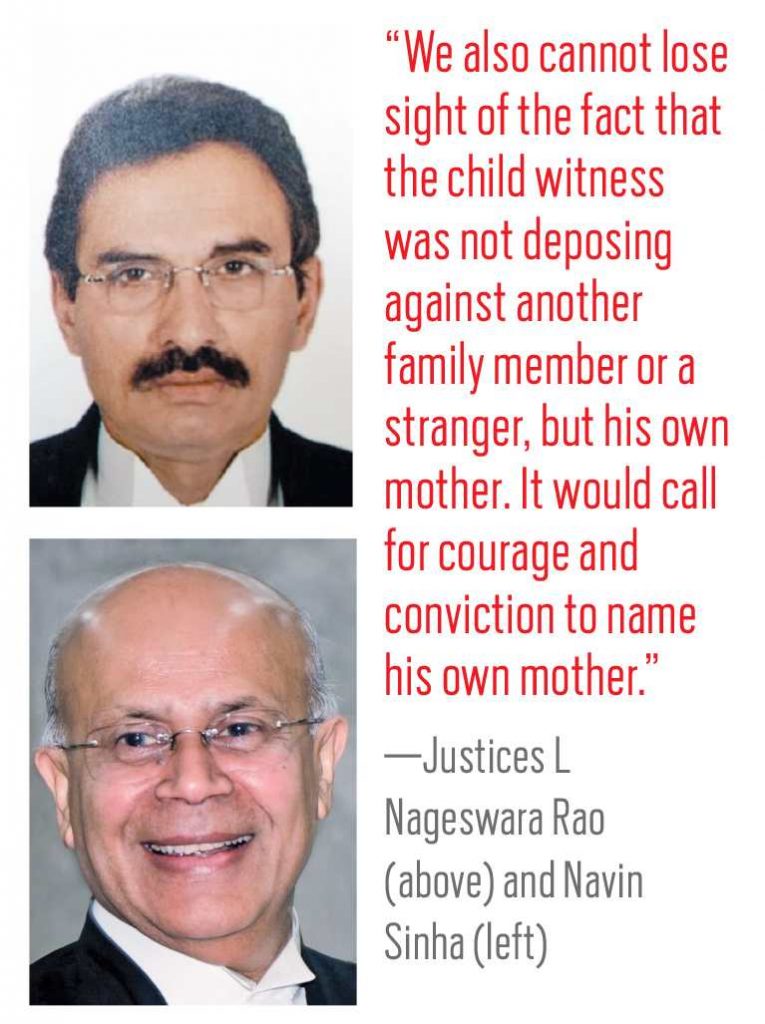

Both these questions were answered on May 26 by a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court comprising of Justices L Nageswara Rao and Navin Sinha. It confirmed the sentences awarded by the trial court and the Punjab and Haryana High Court to the three appellants, including the mother, for the murder. The Court also maintained that the testimony of the child was “reliable” and convincing and the three “stand convicted under Section 120-B, 302, 34 IPC and sentenced to life imprisonment”.

GORY CRIME

The murder took place in the intervening night of March 31-April 1 2007 in Haryana (the apex court order does not identify the place of crime or the identity of the deceased perhaps to maintain anonymity). The killing took place at about 1.30 am in the home of the deceased before his wife and his 12-year-old son. The latter was asked by his mother to alert the neighbour about the crime who reported it to the police the next morning (April 1). The post-mortem revealed that the victim suffered “eight incised wounds and seventeen penetrating incised wounds”.

The Court found the testimony of the child witness reliable and not tutored as alleged by the appellants. In fact, it was on the basis of the boy’s account and the details of the conspiracy hatched by the wife to get her husband bumped off, that the conviction was hinged. The Court noted in its order: “He (the witness) was a school going child aged 12 years. Both, the

trial Court and the High Court have found him to be reliable and convincing. We do not find anything from his evidence to make it suspicious as the result of any tutoring.”

It added: “We also cannot lose sight of the fact that the child witness was not deposing against another family member or a stranger, but his own mother. It would call for courage and conviction to name his own mother, as the child was grown up enough to understand the matter as a witness to a murder.”

EVADING LAW

The two who carried out the physical killing appealed against the trial court order pointing out that the FIR was registered by the police eight hours after the crime was committed, “giving sufficient time for manipulation and false implication”. It was brought to the notice of the court that Prosecution Witness-1 (PW-1), the neighbour, had deposed during cross-examination that about 15-20 villagers had come on hearing the commotion following the murder but none of them had been examined.

The Evidence Act

Section 118 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, states that a child can be a competent witness. But before admitting or recording the statement of a child, the judge must be satisfied that the witness comprehends the questions and has the intellectual capacity and understanding to give an accurate description of what he/she has seen, heard. The law does not fix any minimum age for a witness but his/her competency has to be established by the judge.

In Nivrutti Pandurang Kokate & Ors. v. State of Maharashtra, the apex court dealing with child witnesses observed: “The decision on the question whether the child witness has sufficient intelligence primarily rests with the trial Judge who notices his manners, his apparent possession or lack of intelligence, and the said Judge may resort to any examination which will tend to disclose his capacity and intelligence as well as his understanding of the obligation of an oath.

“The decision of the trial court may, however, be disturbed by the higher court if from what is preserved in the records, it is clear that his conclusion was erroneous. This precaution is necessary because child witnesses are amenable to tutoring and often live in a world of make-believe. Though it is an established principle that child witnesses are dangerous witnesses as they are pliable and liable to be influenced easily, shaped and moulded, but it is also an accepted norm that if after careful scrutiny of their evidence the court comes to the conclusion that there is an impress of truth in it, there is no obstacle in the way of accepting the evidence of a child witness.”

Moreover, it was argued that PW-2, the child witness, admitted not knowing the two assailants earlier. He identified them six months later during dock identification (where a witness identifies defendants in the courtroom or in the dock as being the perpetrators he/she saw at the scene of a crime) for the first time without any test identification parade held before that. So, his testimony could not be safely relied upon as the witness may have had only a “fleeting opportunity” to see those who committed the crime during “the alleged occurrence”.

The Supreme Court dismissed both these arguments. It said in its order: “Considering that the occurrence took place in the dead of night, and PW-1 (the neighbour), being a lady deposed that she proceeded for the police station early in the morning, we find no infirmity to hold that the FIR was delayed, and therefore, may have been a result of prior deliberations.”

The Supreme Court dismissed both these arguments. It said in its order: “Considering that the occurrence took place in the dead of night, and PW-1 (the neighbour), being a lady deposed that she proceeded for the police station early in the morning, we find no infirmity to hold that the FIR was delayed, and therefore, may have been a result of prior deliberations.”

The court also found the behaviour of the wife of the deceased rather peculiar on the night of the murder: “We do find it a little strange, according to normal human behaviour, that at the dead of night, the appellant after witnessing an assault on her own husband, did not rush to the house of PW-1 for informing the same and sent her minor son for the purpose. The fact that she created no commotion by shouting and seeking help reinforces the prosecution case because of her unnatural conduct.”

The order underlined the fact that the child witness was long enough in the room when the assailants committed the murder to identify them later. To quote: “The witness has clearly identified the other two appellants also in the dock, having seen them during the occurrence. The number of injuries on the deceased is itself indicative that the assault lasted for some time enabling identification and did not end in a flash. We, therefore, find no reason to interfere with the conviction.”

The wife’s submission that it was a blind murder (a homicide in which the police has no clues) was not entertained by the apex court. Neither was a speculative submission that her husband had been killed elsewhere and the body dumped at home to falsely implicate her. The Court felt it was “too far-fetched for consideration”. It, therefore, “found no reason to interfere” and dismissed the appeals.