By Inderjit Badhwar

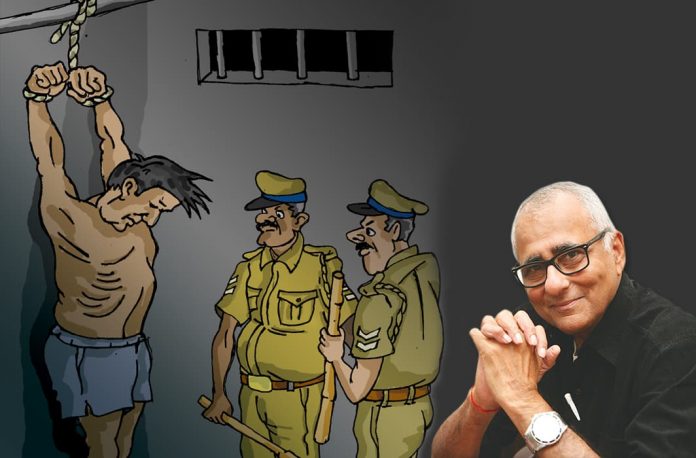

The brutal torture-murder of the father-son duo, P Jayaraj and J Benicks, by the Tuticorin (Tamil Nadu) police and subsequent arrest of some of the alleged perpetrators following a national outrage of protests has focused renewed attention on the latest report of the National Campaign Against Torture (NCAT). The document paints a chilling, horrifying picture of atrocities committed by various police and paramilitary forces in India. It records that the number of custodial deaths during 2019 remained at over five persons per day. The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) of India recorded a total of 1,723 cases of deaths in judicial custody and police custody across the country from January to December 2019.

These included 1,606 deaths in judicial custody and 117 deaths in police custody. Deaths in police custody occur “primarily as a result of torture. In 2019, NCAT documented the death of 125 persons in 124 cases in police custody across the country. Out of the 125 deaths, 93 persons (74.4 percent) died during police custody due to alleged torture, while 24 persons (19.2 percent) died under suspicious circumstances in which the police claimed they committed suicide (16 persons), died of illness (7 persons) and death due to injuries after slipping in police station bathroom (1 person); and the reason for the custodial death of five (4 percent) persons was unknown.

Among the states, Uttar Pradesh topped in deaths in police custody in 2019 with 14 cases, followed by Tamil Nadu and Punjab with 11 cases each; Bihar and Madhya Pradesh with nine cases each; Gujarat with eight cases; Delhi and Odisha with seven cases each; Jharkhand with six cases; Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan with five cases each; Andhra Pradesh and Haryana with four cases each; Kerala, Karnataka and West Bengal with three cases each; Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand and Manipur with two cases each and Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Telangana and Tripura with one case each.

According to the report, “the practice of torturing the suspects in police custody to punish them or gather information or extract confessions continued to be rampant… Some of the victims who were tortured to extract confession during 2019 included a 17-year-old boy (name withheld) in Tamil Nadu who was tortured to death to extract confession in a case of theft”.

What are the remedies available to the victims of police excesses that, aside from the heinous crime of torture, also include wrongful confinement or detention for indefinite periods of suspects still awaiting formal charges and a fair trial?

As I pointed out in my earlier editorial on this subject (read here), the Delhi High Court in Babloo Chauhan vs State Government of NCT, while dealing with an appeal on the issues of fine and awarding of default sentences without reasoning, and suspension of sentence during pendency of appeal, expressed its concerns about wrongful implication of innocent persons who are acquitted but after long years of incarceration, and the lack of a legislative framework to provide relief to those who are wrongfully prosecuted. The Court decreed that the Law Commission of India should undertake a comprehensive examination of the issue of “relief and rehabilitation to victims of wrongful prosecution, and incarceration”. The Court noted: “There is at present in our country no statutory or legal scheme for compensating those who are wrongfully incarcerated. The instances of those being acquitted by the High Court or the Supreme Court after many years of imprisonment are not infrequent. They are left to their devices without any hope of reintegration into society or rehabilitation since the best years of their life have been spent behind bars, invisible behind the high prison walls. The possibility of invoking civil remedies can by no stretch of imagination be considered efficacious, affordable or timely….”

The Law Commission released its report in August 2018. It is a lengthy, scholarly and passionately written document that makes sweeping recommendations for reforms and remedies as outlined in my previous report on this subject. What is noteworthy in the report is the international perspective based on various United Nations Conventions on torture and wrongful incarceration. It cites examples of various other countries which have developed legal frameworks for remedying such miscarriage of justice by compensating the victims of wrongful convictions, providing them pecuniary and non-pecuniary assistance.

These frameworks, the report says, “establish the State’s responsibility of compensating the said victims and also lay down their substantive and procedural aspects of giving effect to this responsibility—quantum of compensation—with minimum and maximum limits in some cases—factors to be considered while deciding the right to compensation as well as while assessing the amount, claim procedure, the institution set up”. Here are some examples:

United Kingdom: In conformity with its international obligations, the United Kingdom has inserted sections into the Criminal Justice Act of 1988, laying down the legislative framework under which the Secretary of State, “subject to specified conditions, and upon receipt of applications, shall pay compensation to a person who has suffered punishment as a result of a wrongful conviction, that was subsequently reversed or pardoned on the ground that there has been a miscarriage of justice—where a new fact came to light proving beyond reasonable doubt that the person did not commit the offence”.

It also provides the factors to be considered while assessing the amount of compensation, i.e. harm to reputation or similar damage, the seriousness of the offence, severity of the punishment, the conduct of the investigation and prosecution of the offence. In terms of the amount of compensation, the sections provide an overall compensation limit (distinguishing on the basis of period of incarceration i.e. less than ten years or ten years or more).

The UK Police Act, 1996, makes the chief officer of police liable in respect of any unlawful conduct of constables under his direction and control in the performance of their functions, “in like manner as a master is liable in respect of torts committed by his servants in the course of their employment; and, accordingly shall as in the case of a tort, be treated for all purposes as a joint tortfeasor.” It further provides for payment of any damages or settlement amount, for such cases, out of the police fund.

Germany: The German Civil Code called “Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB)” lays down provisions regarding “liability in case of official breach of duty” and states as follows: “If an official, intentionally or negligently, violates his official duty towards a third party, he shall reimburse the third party for the resulting damage. If the official is only liable for negligence, he may only be charged if the injured person cannot obtain compensation in any other way.”

United States of America: In the US, matters of miscarriage of justice resulting in wrongful conviction are primarily addressed by compensating those who have been wrongfully convicted in accordance with the federal or the respective state law, as may be applicable. In the federal sphere, a claimant is eligible for relief under this law on the grounds of pardon for innocence, reversal of conviction or of not being found guilty at a new trial or rehearing. These claims lie in the US Court of Federal Claims. The Code provides for a fixed compensation amount depending on the length of incarceration.

All the states in the US have their own respective laws providing for compensation—monetary and/or non-monetary assistance—to the victims of wrongful conviction, incarceration. In terms of monetary compensation, some states have laid down a fixed amount to be paid depending on the period of incarceration. The compensation can vary from $50,000 for each year of incarceration, and $1,00,000 per year for each year on death row.

New Zealand: Wrongful conviction and imprisonment is addressed via compensation granted ex gratia by the State.These ex gratia payments are in accordance with the Ministry of Justice’s “Compensation for Wrongful Conviction and Imprisonment (May 2015) Guidelines”. They provide for three categories of compensation for successful claimants: (i) payments for non-pecuniary losses following conviction—based on a starting figure of $1,00,000 for each year in custody (ii) payments for pecuniary losses following conviction (iii) a public apology or statement of innocence.

Lead Illustration: Amitava Sen