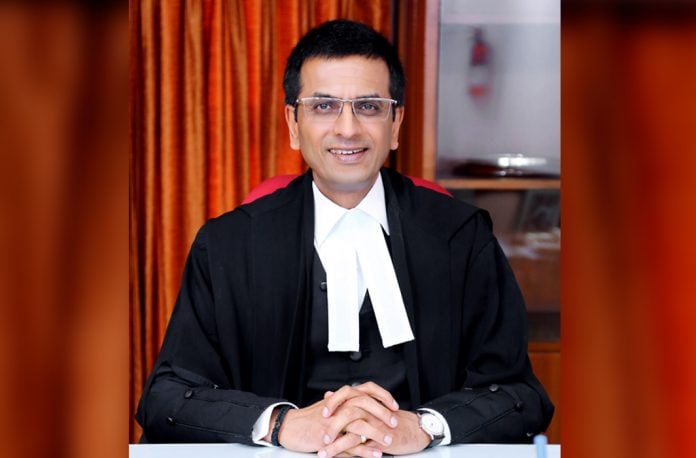

On occasions such as this when a lecture series commemorates the memory of a distinguished personality, it is conventional to begin with words of tribute. But for me personally, the opportunity to speak on this occasion has a deep personal connect. For me, this is homage to the Master. Justice Prabodh Dinkarrao Desai had the unique distinction of being appointed as a Judge of the High Court of Gujarat when he was barely thirty-nine. Over a distinguished career, he functioned as the Chief Justice of three High Courts in succession, those of Himachal Pradesh, Calcutta and Bombay between December 1983 and December 1992.

That a person who was appointed as a Judge of the High Court so young and yet was overlooked by destiny or the powers that be (whichever way one looks at it), must remain in contemporary times as another aberration in the process of judicial appointments. When the call for higher judicial office came, Chief Justice PD Desai preferred to retire from the Bombay High Court: so fiercely was he protective of his own independence and integrity….India as a whole, boasts of significant diversity—heterogeneous along a number of intersecting dimensions, including race, class, religion, and culture. This diversity is further defined across several axes: cultural, social, and epistemic and outlays diverse values, opinions, and perspectives.…In the plural mansion that is independent India, lies a population of over 1.3 billion people comprising several thousand communities.

At the framing of the Indian Constitution, questions arose on how independent India was to account for its heterogeneous polity. Uday Mehta eloquently elucidates the immense range of social realities that the founding members were called upon to address and how the document they gave birth to sought to unify a divergent India by accommodating all people who called India their home. For the founders, the Constitution was premised on both a deep trust in the tolerant nature of its citizens and an unshakeable belief that our diversity would be a source of strength. As Mehta observes, where the population was largely illiterate, the Constitution conferred universal adult franchise. Where the population was diverse and assorted, the Constitution conferred citizenship without regard to race, caste, religion or creed. Where the people were deeply religious, the Constitution adopted the principle of secularism.

Where the Indian State stood united, the Constitution created a federal democracy with all the political instruments necessary for local self-governance. Diversity within the strands of the Constitution is a reflection of the diversity of her people. One cannot exist without the other….The Constitution enacted a complete ban on untouchability and its practice in any form. The Constitution also stipulates that no citizen is to be subject to any disability or condition with regard to access to public spaces and the use of public resources on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth and that the state is empowered to legislate special provisions for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward class of citizens…. In elevating groups as distinct rights holders as well as empowering state intervention to address historical injustice and inequality perpetrated by group membership, the framers located liberalism within the pluralist reality of India and conceptualised every individual as located at an intersection between liberal individualism and plural belonging….The true test of a democracy is its ability to ensure the creation and protection of spaces where every individual can voice their opinion without the fear of retribution.

Inherent in the liberal promise of the Constitution is a commitment to plurality of opinions. However, the litmus test of any claim of commitment to deliberation is assessed by the response of two key actors—the state and other individuals. If you wish to deliberate you must be willing to hear all sides to the story. A legitimate government committed to deliberate dialogue does not seek to restrict political contestation but welcomes it.

As early as the 19th century, Raja Ram Mohan Roy protested against the curtailing of the press and argued that a state must be responsive to individuals and make available to them the means by which they may safely communicate their views. This claim is of equal relevance today. The commitment to civil liberty flows directly from the manner in which the State treats dissent. A state committed to the rule of law ensures that the state apparatus is not employed to curb legitimate and peaceful protest but to create spaces conducive for deliberation. Within the bounds of law, liberal democracies ensure that their citizens enjoy the right to express their views in every conceivable manner, including the right to protest and express dissent against prevailing laws.

The blanket labelling of such dissent as anti-national or anti-democratic strikes at the heart of our commitment to the protection of constitutional values and the promotion of a deliberative democracy. Protecting dissent is but a reminder that while democratically elected governments offer us a legitimate tool for development and social coordination, they can never claim a monopoly over the values and identities that define our plural society. The employment of state machinery to curb dissent instills fear and creates a chilling atmosphere for free speech which violates the rule of law and detracts from the constitutional vision of a pluralist society.

The destruction of spaces for questions and dissent destroys the basis of all growth—political, economic, cultural and social. In this sense, dissent is the safety valve of democracy. The silencing of dissent and the generation of fear in the minds of people go beyond the violation of personal liberty and a commitment to constitutional values—it strikes at the heart of a dialogue-based democratic society which accords to every individual equal respect and consideration. A commitment to pluralism requires positive action in the form of social arrangements where the goal is—to incorporate difference, coexist with it, allow it a share of social space. There is thus a positive obligation on the state to ensure the deployment of its machinery to protect the freedom of expression within the bounds of law and dismantle any attempt by individuals or other actors to instil fear or chill free speech. This includes not just protecting free speech, but actively welcoming and encouraging it.

An equal obligation to thwart attempts to curtail diverse opinions rests on every individual who may not agree with opposing views. Mutual respect and the protection of a space for divergent opinions is the process of viewing every individual as an equal member of a shared political community where membership is not premised on sharing a unanimous opinion…. Taking democracy seriously requires us to respond respectfully to the intelligence of others and participate vigorously—but as an equal—in determining how we should live together. Democracy then is judged not just by the institutions that formally exist but by the extent to which different voices from diverse sections of the people can actually be heard, respected and accounted for. The great threat of pluralism is the suppression of difference and the silencing of popular and unpopular voices offering alternate or opposing views. Suppression of intellect is the suppression of the conscience of the nation.

This brings me to the second threat to pluralism—the belief that homogenisation presupposes the unity of the nation…. As I have stated before, the framers demonstrated a commitment for the protection of India’s pluralist strands. For this reason, amendments to delete the right to propagate religion and to include a ban on dressing that identified with a religion were negatived in the Constituent Assembly.

By negating these amendments, the Constituent Assembly asserted the place of plural expression in the public sphere and signalled a clear departure from the singular unification model. Similarly, even though it was unanimously agreed that the freedom to propagate religion was included within the freedom of speech, the assembly found it necessary to include a specific provision in Article 25 also stating that a heavy responsibility would be cast on the majority to see that minorities feel secure.

A united India is not one characterised by a single identity devoid of its rich plurality, both of cultures and of values. National unity denotes a shared culture of values and a commitment to the fundamental ideals of the Constitution in which all individuals are guaranteed not just the fundamental rights but also conditions for their free and safe exercise. Pluralism depicts not merely a commitment to the preservation of diversity, but a commitment to the fundamental postulates of individual and equal dignity.

In the creation of the imagined political community‘ that is India, it must be remembered that the very concept of a nation state changed from hierarchical communities to networks consisting of free and equal individuals.

India, as a nation committed to pluralism, is not one language, one religion, one culture or one assimilated race. The defence for pluralism traverses beyond a commitment to the text and vision of the Constitution‘s immediate beneficiaries, the citizens. It underlines a commitment to protect the very idea of India as a refuge to people of various faiths, races, languages, and beliefs.

India finds itself in its defence of plural views and its multitude of cultures. In providing safe spaces for a multitude of cultures and the free expression of diversity and dissent, we reaffirm our commitment to the idea that the making of our nation is a continuous process of deliberation and belongs to every individual. No single individual or institution can claim a monopoly over the idea of India….

Finally, the commitment to pluralism lies in the constitutional trust expressed by the framers on every individual.… An example of this constitutional trust and obligation is evident in the divergent view of the relations between majorities and minorities upon India gaining her independence.

During the colonial rule, the Morley-Minto reforms recommended separate electorates for minorities. This recommendation for the first time introduced identity politics into the Indian regime by classifying groups as majority and minority.… When the Constituent Assembly was called to decide the fate of separate electorates in independent India, they decided that its inclusion was not essential to and even contrary to the requirements of a pluralistic society. They rejected separate electorates and dismissed the relevance of numerical disadvantage in a polity….

The framers of the Constitution rejected the notion of a Hindu India and a Muslim India. They recognised only the Republic of India. As one member of the Constituent Assembly said—we should proceed towards a compact nation, not divided into different compartments but one where every sign of separatism should go. As another member said—there will be no divisions amongst Indians. United we stand; divided we fall….What is of utmost relevance today, is our ability and commitment to preserve, conserve and build on the rich pluralist history we have inherited. Homogeneity is not the defining feature of Indians.

MA Kalam, a celebrated anthropologist wrote in a piece that: “a visible, discernible, lively and successful engagement with diversity is pluralism indeed. This definition calls upon us to look at each other and recognise that our differences are not our weakness.” Our ability to transcend these differences in recognition of our shared humanity is the source of our strength. Pluralism should thrive not only because it inheres in the vision of the Constitution, but also because of its inherent value in nation building. Today I have attempted to share with you the vision and spirit of pluralism that I believe has always defined India. India is a sub-continent of diversity unto itself. The mere mention of India evokes in every person a different idea which they associate with the nation.

Anybody truly conversant with Indian history will tell you that the single defining hallmark of ancient India was its divergent, scattered and fragmented nature. It has been for centuries a land of vibrant diversity of religion, language and culture. Pluralism has already achieved its greatest triumph—the existence of India.

The creation of a single nation out of these divergent and fragmented strands of culture in the face of colonial tyranny is a testament to the shared humanity that every Indian sees in every other Indian. The nation’s continued survival shows us that our desire for a shared pursuit of happiness outweighs the differences in the colour of our skin, the languages we speak or the name we give the Almighty.

These are but the hues that make India and taking a step back we see how altogether they form a kaleidoscope of human compassion and love surpassing any singular, static vision of India. Pluralism is not the toleration of diversity; it is its celebration.