His Swansong

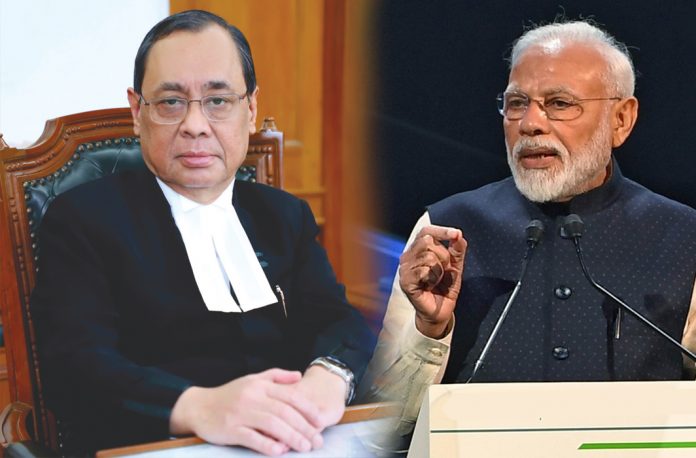

With a little more than 10 days that remained until he retired on November 17th, 2019, India’s bespectacled, scholarly-looking 46th Chief Justice, Ranjan Gogoi, 64, wrote his swansong in a series of high profile judgments which emanated rapid-fire from the highest court of the land over which he had presided as master of the roster since October 3, 2018.

Some 10 cases listed before him included – not necessarily in order of importance, the long-drawn-out Ayodhya masjid-mandir dispute; the Sabarimala tussle, which was referred to a seven-judge bench even as the Court continued to uphold the right of women to pray inside tee erstwhile men-only temple; dismissal of the politically contentious review petitions seeking to re-examine the Court’s December 14, 2018 verdict which said that there was no corruption in the Rafale fighter jets deal; confirmation that the Chief Justice of India’s office comes under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, emphasising that “in a constitutional democracy judges can’t be above the law”; closure of the contempt case against Congress supremo Rahul Gandhi with the admonition that Gandhi needs to be more careful with what he says. The cased filed against Gandhi alleged that he had wrongly linked his slogan “chowkidar chor hai” against Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the Rafale allegations to the Supreme Court.

In his parting speech, the retiring chief justice said that as an institution “we have tried to deliver much more than what is reasonably possible, yet, today each of us is required to deal with new challenges, which unfortunately arise from within and outside of our court complexes and our judicial processes.”

“Within our court complexes, there is an increasing indifference to the decorum and discipline that were always the hallmark of our institution. Sadly, such indifference lies more among some of the stakeholders who are part of the justice delivery infrastructure, yet are completely indifferent to its health and progress…

…The indifference of such stakeholders to the dignity of our institution has reached new lows in the recent past, as rank hooliganism and intimidatory behaviour has become the order of the day in some pockets of our court system. This has to be acknowledged, so that its vicious designs are defeated and the glory of our institution stands uncompromised..

I would say that the time has come that the high courts shake off the sense of any inertia and play an active part as the true guardian of all court complexes under their jurisdiction as well as of the judicial process, besides safeguarding the well-being of our judges and the magistrates there.” His remarks were seen as a response to the week-long ugly spectacle of Delhi High Court lawyers and policemen battling one another on the streets.

The Rebel Within

These were indeed stirring words, and the first chief justice from the state of Assam is known to have a gripping and compelling turn of phrase when he wants to as some of the quotes at the end of this article will demonstrate. But more than is farewell speech and, perhaps in equal importance to the cases he presided over as his term ended, Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi will probably be best remembered for the mutinous press conference in which he participated on January 11, 2018, along with three senior Collegium judges in which they jointly cast serious aspersions on the functioning of the Supreme Court under then CJI Dipak Misra. At stake was the future of “democracy” itself, they averred pointing out flaws in the system of judicial appointments and assignment of cases.

In fact, the nation was left guessing whether Gogoi, who was the second seniormost judge, would be named successor to Misra the following October after Misra’s retirement, as has been the traditional practice. It was surmised that the government may sit on his appointment out of sheer pique stemming from his participation in the “judges’ revolt” the indirect target of which was the executive branch for its attempts at politicizing the judiciary.

But high-level sources indicated that such speculation was unwarranted not only because Misra, who is not known to be a vindictive man would follow the laid down procedure and recommend Gogoi, but also, more importantly, because the government, particularly officials close to the law ministry had opened back-channel discussions with persons close to Gogoi to ensure that he would not be unjustly hostile to the government in important cases, such as Ayodhya, which would be coming up before Constitutional benches.

Apparently assured that it would not be facing a hostile CJI, the government facilitated a smooth succession instead of any attempt at procrastination or supersession which may have sparked off a constitutional crisis. In fact, Justice Gogoi had repeatedly demonstrated that he would not be swayed by concerns other than those which motivate him.

Transfer Politics

Sadly, the Collegium, has not been able to avoid public scrutiny under Gogoi’s stewardship, and the “judges’ mutiny” of January, 2018 has been overtaken by other controversies. Hardly had the recent brouhaha over the dramatic about-face on the Collegium’s decisions on elevation of two judges to the Apex Court died down than another hullabaloo erupted. News broke out in high judicial circles that the government was sending signals to the Collegium to transfer the high profile Justice S Muralidhar out of Delhi High Court. He had often been the target of Right-Wing ideologues.

Muralidhar was widely admired for his uncompromising opposition to communal violence and his defence of personal liberty and Article 21 of the Constitution. He was critical of the incarceration of intellectuals like Gautam Navlakha, for alleged Maoist links. He convicted members of UP’s PAC in the 1986 Hashimpura slaughter. He also led the bench that slammed former Congress MP Sajjan Kumar into jail in a case related to the 1984 anti-Sikh pogrom.

The proposal met with considerable resistance from senior judges NV Ramana, Sanjay Kishan Kaul, and AK Sikri. In fact, matters came to such a head that Kaul is believed to have said he would call an open press conference to register his dissent. Sikri suggested that the decision could wait until after his retirement in March. To his credit, Gogoi, rather than risking further public debate, stood up for the integrity of his institution and deferred the move. Sources close to Gogoi made sure that the CJI was given due credit for taking a stand.

This is not the first time that Gogoi’s name has been indirectly mentioned in reference to a transfer or posting. The CJI is known to be a good family man who develops close ties within the system and is loyal to those he admires even if they at times they attract controversy.

For example Delhi High Court Judge the late Valmiki Mehta is related to Gogoi through marriage. Gogoi’s daughter is married to Mehta’s son, Tanmay, who is emerging as a high profile lawyer in the courtrooms of the capital. His relationship to the CJI was commonly known in the power circles but Gogoi reportedly kept at a safe distance from him. Similarly, he also kept at arms-length from his son, Raktim Gogoi, a high profile lawyer based in Delhi whose flashy lifestyle and preference for expensive cars had once allegedly caught the attention of the Enforcement Directorate.

Judge Valmiki Mehta had also courted controversy. Two years ago, when TS Thakur was CJI he had ordered Mehta to be transferred out of the Delhi High Court to the Andhra/Telengana High Court. In fact, when the Law Ministry sat on this recommendation, Thakur threatened to withdraw all judicial work from Mehta. And before his retirement, Thakur had asked the government to file a detailed report on why the recommendations of the Collegium had not been carried out in this case. Justice Mehta continued to enjoy his tenure in the Delhi High Court.

Sexual Harassment Imbroglio

Perhaps the saddest episode to engulf Gogoi during his entire career was the sexual harassment case against him—something that his friends say hurts him deeply even to this day. Following a complaint against the CJI in a sexual harassment case, an SC in-house panel which probed it came to the conclusion that there was no substance in it. The committee said it found “no substance in the allegations” made by a former woman staffer of the apex court that the CJI had sexually harassed her and after she rebuffed his advances, she and her family were targeted and victimised. The in-house panel comprised Justice SA Bobde, the second most-senior judge in the SC, Justice Indu Malhotra and Justice Indira Banerjee.

“The In-House Committee has submitted its report dated 5.5.2019 in accordance with the in-house procedure to the next senior judge competent to receive the report and also sent the copy to the judge concerned, namely, the chief justice of India,” a press release signed by the Supreme Court’s secretary-general stated. Referring to the Court’s judgment in the 2003 Indira Jaising case, the panel added that its report constituted a part of the in-house procedure and therefore it was not liable to be made public. Protests followed the announcement, not just from women’s groups and activists, but several senior advocates. The police imposed Section 144 around the precincts of the apex court and several lawyers and activists were detained.

In a statement released to the press, the complainant said that she was not just “highly disappointed and dejected” to learn that the in-house committee appointed by the Supreme Court found “no substance” in her sexual harassment complaint, but also felt that “gross injustice” had been done. “The committee has announced that I will not even be provided a copy of the report, and so I have no way of comprehending the reasons and basis for the summary dismissal of my complaint of sexual harassment and victimisation. Today, I am on the verge of losing faith in the idea of justice,” she said.

Later in the day, several senior advocates appearing on TV shows said the report could be challenged not just by the aggrieved person but by anybody. The general refrain was that the charges were not against any ordinary person but against the chief justice.

No sooner had the charges become public than the CJI suo moto constituted a special bench comprising CJI Ranjan Gogoi and Justices Arun Mishra, SanjivKhanna on Saturday to adjudicate into the sexual harassment complaint.“We are not passing orders on allegations but media should show restrain to protect independence of judiciary,” the bench said.

The CJI said: “Independence of judiciary is under very serious threat and there is a “larger conspiracy” to destabilise the judiciary. There is some bigger force behind the woman who made sexual harassment charges. “If the judges have to work under these conditions, good people will never come to this office. After 20 years I have bank balance of 6,80000 and the issue in hand, my brothers will consider, not me and the seniormost judges will consider this issue.”

Loyalty Begets Loyalty

As they say, in the real world, loyalty often begets loyalty. Justice Gogoi is known to admire J&K High Court Judge Ali Mohammad Magrey whom he helped appoint as chairman of the State Legal Services Committee when Gogoi was himself the Executive Chairman of NALSA. Magrey was also inducted as Kashmir’s first judge into NALSA. Magrey landed himself into a spot of controversy when word got out that his daughter had been inducted into the state legal aid body under allegations of favouritism in which the name of retired state Judge Hasnain Masoodi also figured. Masoodi headed the State Selection Cum Oversight Committee.

The induction of Magrey’s daughter sparked off a prolonged inquiry by the Supreme Court. But Gogoi, as a demonstration of his fairness and loyalty attended the marriage of Magrey’s son in Kashmir and also enjoyed a small vacation at the scenic Putney Top tourist attraction.

Kashmiris are known for their hospitality and generosity to whom a guest is like a God. Gogoi has a fondness for cuisine and fish, and his visits to the valley have attracted him to the delicious flavor of fresh water trout which is abundant in the crystal clear river waters near Pahalgam and Achhabal.

As a gesture of his admiration, respect, and loyalty to the Chief Justice, Magrey regularly air-parcelled fresh trout for the CJI’s dining pleasure.

More recently, as a show of solidarity with a proud son of Assam, the Guwahati High Court decided to provide post-retirement facilities to Gogoi after his retirement. The full court of the Guwahati High Court has decided, in a resolution adopted by the protocol committee at its meeting on 30 October to accept the following proposals: “A dedicated Private Secretary to look after day to day requirement of his lordship and madam. The PS, in addition to discharging whatever duties entrusted to him, may also coordinate with the registry for any protocol-related requirements.

“One Grade 4 Peon and one Bungalow Peon to be made available at the Guwahati residence of hisLordship. A chauffeur-driven vehicle belonging to the High Court in good condition be made to his Lordship on fuel basis as and when required.

“A nodal officer be identified from the Registry to coordinate with the Private Secretary.CJI Gogoi had started his practice at the Guwahati High Court. He served in the Guwahati HC before being elevated to the Supreme Court. Last year, he took as the chief justice of the India. In view of the fact that he has chosen to settle down in Guwahati after his retirement, as an institutional courtesy, the protocol committee of the HC proposes that the courtesies be extended to him”.

Controversy And Enigma

People in the know have welcomed this as a show of judicial solidarity. Some observers. however, view the CJI as an enigma whose actions may, sometimes, not comport with varying positions he takes in public. For example, at a time when India’s institutions seem under organized attack from an insecure and self-serving political establishment, the recent words of Gogoi came as a breath of an invigorating breeze: “Independent journalists and sometimes noisy judges are democracy’s first line of defence”. In that same speech Justice Gogoi favored a more pro-active judiciary.

But shortly afterwards, when the Supreme Court learned of ousted CBI director Alok Verma’s deposition before the CVC from the newspapers even before the official report had been handed over in a sealed envelope to the Court, as it had ordered, Justice Gogoi’s reaction in open court was swift and harsh.

Thundered the chief justice: “What is this? We will not hear you today. None of you deserve a hearing,” Senior Advocate Fali Nariman, representing Verma, emphasised that stories were on Alok Verma’sresponses to questions the CVC put to him. These were not in a sealed cover and were not meant for the Supreme Court. But the Court remained unmoved. It refused to take on record the reason for adjournment of the hearing. “For reasons which the court is not inclined to record”, the hearing was deferred to the end of the month.

The Verma “leak” was not the only matter pertaining to the press that annoyed the chief justice. Almost simultaneously, another story appeared featuring Deputy Inspector General Manish Kumar Sinha who had been probing corruption charges involving CBI special director Rakesh Asthana also moved the apex court challenging his transfer to Nagpur. In his plea to the Court he alleged interference by National Security Adviser (NSA) Ajit Doval.

“The transfer was arbitrary, motivated and mala fide, and was made solely with the purpose and intent to victimize the officer as the investigation revealed cogent evidence against certain powerful persons,” Sinha said. The Supreme Court, however, denied an urgent hearing into this case.

Gogoi expressed further displeasure over this matter also having appeared in the press: “Here is a litigant who mentions it before us and then goes out to distribute the petition to everyone…This court is not a platform for people to come and express whatever they want… This is a place where people come for adjudication of their legal rights. This is not a platform and we will set it right.”

The corridors of the Supreme Court are still abuzz with controversial arguments about why the CVC’s report should have been delivered under sealed cover (were national security secrets involved), and why the “service related matter” regarding the summary removal of Verma without recourse to due process could not have been taken up separately from the charges and counter-charges of corruption within the CBI.

This is ironical in view of Justice Gogoi’s own demonstrated advocacy of a free and fearless press. Below are excerpts from the stirring speech he made a few months ago at the third Ramnath Goenka Lecture in New Delhi:

•Not too long back, I had read an interesting news article talking about the surprising surge – which is not so surprising, all things considered – in the sale of George Orwell’s 1984 in the United States. That piqued my interest in revisiting the classic. And, for some reason, I want to recollect a thought from it today. “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.”

•(Ramnath Goenka) could call Spade a Spade. Someone who could speak truth to power. Even if it came at a cost. To be ready to break, but not bend could be called obstinacy by some, and determination by others. Is it a matter of perspective? I do not know. And, I cannot say for others but as far as I am concerned, I only feel that we need to ask ourselves some questions: Where is the Goenka in us; his ideals; his values?

•The judiciary must certainly be more pro-active, more on the front foot. This is what I would call as redefining its role as an institution in the matters of enforcement and efficacy of the spirit of its diktats, of course, subject to constitutional morality (= separation of powers).