By Nikhil Goel

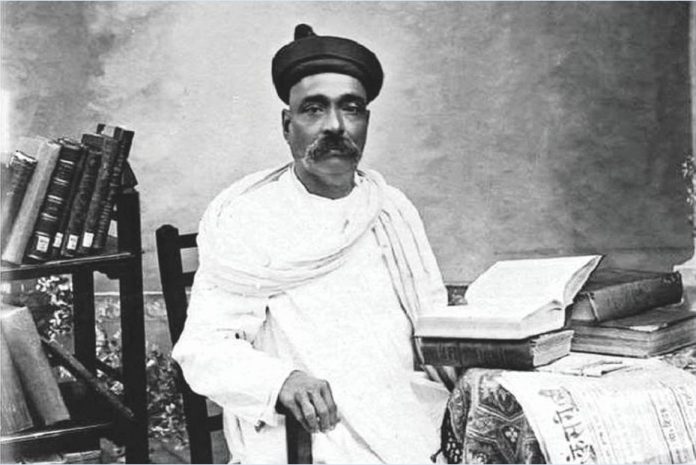

During a recent hearing, Justice DY Chandrachud, senior judge of the Supreme Court, revealed the significance of some immortal words of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a towering leader of India’s Independence movement. The remarks of Justice Chandrachud were inspired after he saw a painting in the background of the appearing Senior Counsel. He revealed that he had read those words every day when he was in that High Court as the words had great significance for justice.

This is not surprising as the immortal words represent a courageous willingness to suffer for a cause. The plaque carrying these words is installed on the second floor of the Court, just outside the central court where Tilak’s trial took place in 1908. The words are: “In spite of the verdict of the jury, I maintain that I am innocent. There are higher powers that rule the destiny of men and nations and it may be the will of providence that the cause which I represent may prosper more by my suffering than by my remaining free.”

There is no doubt that there is jurisprudential value in the words of Tilak. Everyone knows that Tilak was one of the most eminent revolutionaries who fought and guided the freedom movement of India. He gave the slogan, “Freedom is my birth right and I shall have it”. He was part of famous trio—Bal, Pal, Lal. His writings remain immortal and will continue to inspire Indians for centuries. Article 51A(b) of the Constitution makes it the constitutional duty of every citizen “to cherish and follow the noble ideals which inspired our national struggle for freedom”. In the 75th year of Independence, which is being observed as “Azadi ka amritmahotsva”, let us consider the jurisprudential significance of the words of Tilak.

The trial of Tilak in 1908 was on the charge of sedition due to an article of his in The Kesari. It was about the rather repressive measures adopted by Her Majesty’s government in response to rising cases of bomb violence. In fact, the first article on May 19, 1908, was a commentary on the incident in which Subhas Chandra Bose threw a bomb on the carriage of what he believed was carrying Magistrate Douglas Kingford. Unfortunately, the target of the bomb was in another carriage and two British women were killed.

Tilak, in his trademark voice, called such repressive measures “A Country’s Misfortune”. This was followed by another article titled These Remedies Are not Long Lasting on June 9, 1908. Her Majesty’s government, ever in thrall of itself, could hardly permit such “disaffection” to be spread, especially in a newspaper that had a circulation of 6,000 or so.

During the trial itself, Tilak chose to represent himself. Records of the trial show that his defence was not only formidable, but put to the sword the very provisions that he was sought to be convicted under. In fact, commentators have stated that the second trial of Tilak, though ostensibly titled Emperor vs Bal Gangadhar Tilak, was actually Tilak vs Colonial Legal Order. The trial records reveal that the jury was unable to unanimously agree and the split was 7:2. In fact, Davar J felt compelled to speak rather harshly through his judgment, calling the articles something that only a perverse or diseased mind could encourage. In response to this, Tilak stated the words that are now immortally written in stone.

It is significant that Tilak presented to the nation a selfless idea, so selfless that even when being sentenced to transportation to Mandalay, he saw it as a victory. Today, there is talk of repeal of the sedition law. It is well known that judgment in Tilak’s case (1898) which was approved by the Privy Council, has since been reversed by the Supreme Court in Kedar Nath Singh vs State of Bihar, 1962 as being against Article 19(1)(a).

Another significant aspect is infallibility of the justice dispensation and recognising that there are “higher powers that rule the destiny of men and nations” which need not in any manner be taken as a rejection of the system of justice dispensation. This is also reflected in the emblem of the Supreme Court—“Yato dharma tatojay (Righteous is victorious)”. This means that victory is not being confined merely to winning or losing a case but in being righteous and the Court’s endeavour constantly is to uphold righteousness. This is the foundation of “Dharam Rajya”—rule of righteousness. Let our jurisprudence be inspired by righteousness, inspired by immortal words of Tilak, our greatest revolutionary leader.

Author is an Advocate practising in the Supreme Court of India and the Delhi High Court. Currently, the author is also functioning as Special Public Prosecutor for the CBI and Additional Advocate General for the States of Karnataka and Haryana.