Is the Narendra Modi aura finally waning? It may be too early to say so with certainty but this is a question worth posing.

From a regional leader, Modi metamorphosed into a national icon in 2014, leading the BJP to an unprecedented Lok Sabha victory. But the party’s victory march did not stop there. Pregnant with hope as the times were, the BJP won Haryana, where it had no prior electoral base. It also went on to win Maharashtra and Jharkhand in the same year.

The appeal of Modi was spilling on from the national stage to the regional electoral arenas of a country with dazzling diversity. And with this the BJP was becoming synonymous with Modi, who was becoming larger than the party itself.

There were few reverses the party faced, apart from Delhi and Bihar, where the alliance of JD(U) and RJD defeated it.

The party took Assam and dramatically defeated the CPI(M) in Tripura. A post-poll alliance of the Congress and JD (S) halted it in Karnataka. It was only late in 2018 that Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh halted its victory marches, till another Modi wave post-Balakot led to an even bigger BJP victory in 2019, followed by the core ideological agenda of revocation of Article 370 — which gave Jammu and Kashmir special status — being fulfilled.

However, the recent months have seen dramatic reversals in state elections, with Jharkhand being the latest instance. The JMM-Congress-RJD alliance is set to clinch a clean victory in Jharkhand, with the BJP, which could not strike an alliance with the All-Jharkhand Students’ Union (AJSU), suffering losses.

This, then, is the difference between Modi’s BJP in 2014 and in 2019. The Lok Sabha surge of 2019 is being unable to translate into regional victories months after it. Anti-incumbency is being able to rattle the BJP the way it rattles any other party. The Modi wave – which has been alive at the Central level – is unable to make the BJP make regional politics irrelevant.

The defeats are deeper in the sense that they come at a time when the BJP is pursuing a very centralised politics, fulfilling its core Hindutva agenda and also projecting Modi and his core agendas as issues on which state polls are to be contested. And the reverses come in the core regions of the BJP rather than in peripheral regions. After Haryana and Maharashtra, Jharkhand confirms this trend.

It is possible to argue that these defeats are just like the three electoral reverses the BJP faced late in 2018; that national politics is about Modi and regional politics about local issues. Only time will tell if this is the case.

But there is no doubt that unlike 2014, the Modi of 2019 cannot deliver victories in state polls.

The defeats of the BJP in state polls over the last one year also mean that the party no longer rules most states. It now rules only in pockets, with larger swathes of the country under non-BJP and non-NDA governments.

Indeed, Modi’s ideologically sharpest hour in 2019 is also a time of electoral reverses. The second Modi government is the one that revoked Article 370. It was during this government’s term that the Supreme Court verdict in the Ayodhya title suit went in favour of Hindu litigants, something that BJP supporters rejoiced. The issue of illegal immigration – something the RSS has always been concerned about — has also been brought forth sharply with the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, adding a Muslim filter that is in sync with Hindutva even if it is constitutionally suspect.

It is at this time that the BJP has been unable to form governments in two of the three states that went to polls in recent months. It has also lost its only ideological ally, the Shiv Sena, in 2019.

Since the BJP had made it clear that elections would be fought on ideological grounds – like the revocation of Article 370 – the electoral failures, which may be local in many senses, are symbolic reverses for the Modi-Shah duo as also the core agenda that is being speedily pursued now.

With these defeats, it is also clear that the BJP will not be able to have a majority in the Rajya Sabha, and passage of its Bills will depend on the Opposition and undecided regional parties. In other words, rather than practising a strongly centralised, top-down, politics, the BJP will have to reach out to political parties. Constitutional amendments – which need a majority in both Houses and cannot be passed through a joint sitting of the two Houses – will be almost impossible to pass unless the Opposition is on board.

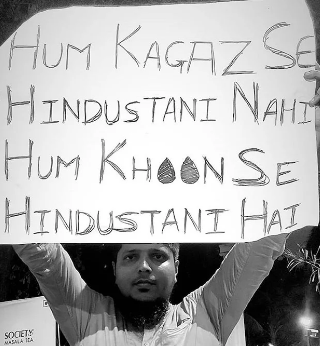

The discourse of the strong leader in full command is under challenge – in state elections and even on the streets, if the anti-CAA protests are anything to go by.

Modi’s statement that there is no thought yet on a nationwide NRC – despite the statement by Amit Shah in Parliament and the construction of a detention centre as far as Karnataka – just goes to show that the Prime Minister may be thinking of putting the core agenda of an NRC alongside CAA on hold, at least for a short while.

All signs suggest that Modi is no longer what he was in 2014, and since the BJP has been reduced to a Modi-Shah party, this may not be great news for it.

-Author-

–Dr.Vikas Pathak teaches at the Asian College of Journalism, Chennai