A day after President Ram Nath Kovind appointed four new judges to the Supreme Court last September and four days before they were actually sworn in as Justices of the top court, the court registry announced the creation of two new court rooms within the premises.

“It is hereby circulated for the information of all concerned that as per the orders of Chief Justice of India, two additional courtrooms have been created near the existing court number 10 which have been numbered as court number 16 and court number 17,” said the court registry in a note.

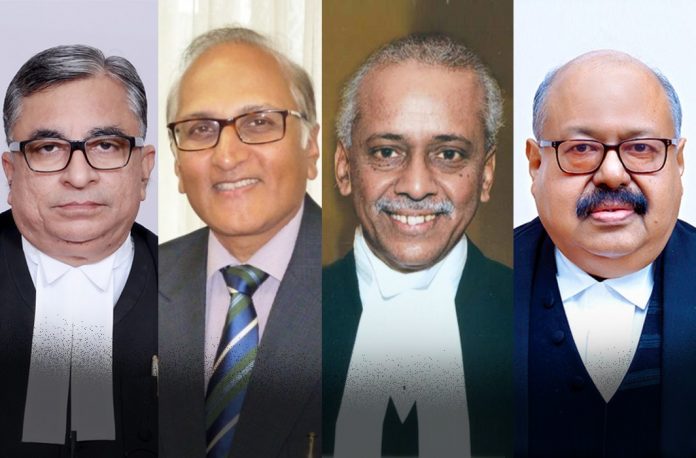

Yet more than four months after they were sworn in, the four judges—– former Himachal Pradesh Chief Justice V. Ramasubramanian, former Punjab and Haryana Chief Justice Krishna Murari, former Rajasthan Chief Justice S.A. Ravindra Bhat and former Kerala Chief Justice Hrishikesh Roy—– have not got official accommodation and continue to work out of state guest houses.

The situation came about, keeping in mind the huge backlog of cases across the country from the lower courts to the country’s top court. According to official figures, there are over three crore cases pending in the lower and districts, 44 lakh cases in the country’s 25 high courts and nearly 60,000 cases in the apex court alone. It was with a view to tackle the backlog in the SC that the government increased the strength of SC judges from 31 to 34, including the Chief Justice of India. The government took the step after the then CJI Ranjan Gogoi wrote to the Prime Minister Narendra Modi to increase the number of judges in the top court. The CJI reasoned that due to paucity of judges, the required number of constitution benches to decide important cases involving questions of law were not being formed.

The Supreme Court (Number of Judges) Act, 1956 originally provided for a maximum of ten judges (excluding the CJI).This number was increased to 13 by the Supreme Court (Number of Judges) Amendment Act, 1960, and to 17 in 1977. The working strength of the Supreme Court was, however, restricted to 15 judges by the cabinet (excluding the Chief Justice of India) till the end of 1979. But the restriction was withdrawn at the request of the Chief Justice of India.

Though the strength of the SC has increased by 60 per cent in the last three decades, no thought has apparently been given to the accommodation for the judges. In 1988, its strength was increased 18 to 26 and more than 20 years later, in 2009 it was further increased to 31 to expedite disposal of cases.

But accommodation for the judges has not quite kept pace with the increase in their numbers. Supreme Court and high court judges are entitled to Type VIII and Type VII bungalows having four to five bedrooms, besides servant quarters, front and rear lawns and garage. These are mostly located in Lutyens’ Zone Akbar Road, Ashoka Road, Krishna Menon Marg, Moti Lal Nehru Marg, Tughlak Road and the newly built New Moti Bagh Complex. It is learnt that there are 32 bungalows allotted to Supreme Court judges, which technically means that only two of the four of the new judges appointed should be without an official roof over their heads.

But the problem arises due to many retired judges being appointed as heads of watchdog bodies, tribunals, regulatory bodies and such like. Delhi is already home to over 40 tribunals and other bodies presided by former judges of the Supreme Court. In most cases, they are appointed to the new posts immediately on their retirement as SC judges. Thus they seldom feel the need to pack up and move to new premises. They simply continue to stay on, leaving the officials of the housing ministry scratching their heads searching for a place for the new judges to be put up.

There could be no more telling example of this than the panel headed by a retired Supreme Court judge that was set up to resolve the water dispute between Punjab and Haryana under the Punjab Accord of 1985. After 24 years, the panel — the Eradi Commission —–which cost the exchequer Rs. Nine crores was wound up with the dispute still unresolved. All the while, Justice V Balakrishna Eradi continued to stay in a Lutyens Delhi bungalow with manicured lawns the size of a football field.

The Law Commission had suggested that merely increasing the number of judges without improving infrastructure in the courts would do little to help address delays. Among the steps recommended to improve infrastructure was the creation of a specialized service to provide critical administrative support to judges from the lower courts all the way to the apex court. Judges would then be able to devote their time to judicial activity.

Meanwhile, the four newest judges of the apex court continue without an official roof over their heads.

— India Legal Bureau