By Inderjit Badhwar

In an unprecedented move, Rajasthan Police’s Special Operations Group has filed FIRs and started criminal investigation of no less a political bigwig than Union Minister GS Shekhawat along with one of the BJP’s top honchos Sanjay Jain and suspended Congress MLAs Bhanwar Lal Sharma and Vishvendra Singh. The probe centres on charges of humongous bribes aimed at luring away state legislators in an effort to pull down the ruling Congress government of veteran warhorse Ashok Gehlot, the blue-eyed boy of 10 Janpath’s Old Guard led by Sonia Gandhi.

But the unfolding events are more than a tale of personalities involving wannabe chief minister Sachin Pilot, 42, an accomplished and battle-hardened Congress (hitherto) rising star and a symbol of the party’s Gen Next straining at the leash against the likes of Sonia advisers Ahmed Patel, Veerappa Moily, Ghulam Nabi Azad, et al. At a macro political level, the shenanigans are yet another manifestation of the quagmire of greed, ambition, degradation and cynicism in which the national political system is bogged down.

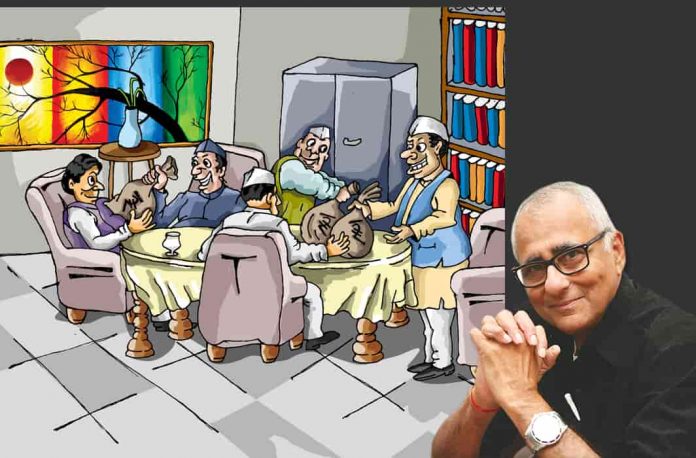

Welcome back to déjà vu. In other words, what else is new? We’ve seen popularly elected state governments come and go through the device popularly known in India as “horse-trading” wherein lawmakers elected on the tickets and platforms of one party simply switch in small numbers or in larger groups, depending on the size and majority of the lawfully elected government, for positions and monetary allurement, or protection against criminal cases they may be facing. Some of the recently recorded examples of governments being pulled down or cobbled together via unholy alliances as ruling entities post-elections even though they got clobbered by the public vote include Goa, Uttarakhand, Manipur, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh.

Most of these cases wind up in the courts. They ultimately reach the Supreme Court. And the courts have almost universally condemned horse-trading because it nullifies the real mandate of the people and the purpose of the anti-defection law embedded in the Tenth Schedule. In the absence of meaningful legislative electoral reform—which is anathema to the political class—all that the courts can do is to thunder against the evil and take action that will either delay or stymie parties from carrying out coups against elected governments through devices used by the perpetrators such as delaying floor tests and thereby opening up windows of endless opportunities to induce, cajole and bribe.

In November 2019, when the case of the 17 MLAs who had resigned in order to bring down the HD Kumaraswamy JD (U)-Congress government came to the Supreme Court, Justice NV Ramana opined that Parliament “should consider strengthening certain aspects of the Tenth Schedule so that such undemocratic practices (such as defection) are discouraged and checked”. The object and purpose of the Tenth Schedule, the Justice observed, was to curb the evil of political defection, “motivated by the lure of office or rather similar considerations… Horse-trading and corrupt practices associated with defection and change of loyalty for lure of office or wrong reasons have not abated. Thereby the citizens are denied stable governments”.

In a similar vein, Justice DY Chandrachud, who wrote the opinion on the Madhya Pradesh imbroglio that brought down the Kamal Nath government in March 2019, was unstinting in his criticism of the political class. It was best described by Supreme Court advocate Jai Anant Dehadrai: “Unsparing in its disgust for an apparently unquenchable and ‘we-will-stop-at-nothing’ lust for power, the Court was then constrained to note that this case had once again ‘shone a light on the often-fluid allegiances of democratically elected representatives’. Holding the proverbial mirror to our elected representatives, the Court wondered how their conscience could permit such egregious conduct. The Judgment ends with an affirmation that a Constitutional Court’s duty is to uphold democratic values while maintaining ‘an arm’s length from the sordid tales of political life’.”

Our cover story this week by attorney-journalist Neeraj Mishra (read here) says it all in the opening para: “It seems like the rerun of last season’s hit and the opening scene is always the same: luxury bus full of boisterous MLAs entering a luxury resort flashing the V sign. It seems to be happening with dreadful regularity every time a Rajya Sabha election approaches or as soon as rumours of a shaky state government take hold. We know what they are happy about but it’s inexcusable that they have to feel victorious after decimating the best tenets of electoral democracy.”

The drama is being played out as regularly on national TV as the latest Covid figures. As we watch with a mixture of disgust and amusement, we forget that these theatricals omit an essential message. What is the path to reform? When will democracy cease being a spectacle and become a living, breathing element of the growth and progress and value system of this nation as expressed in the Constitution bequeathed to us by the Founding Fathers?

As the story points out, The Representation of the People Act, 1951, does not offer much security to voters. It has no option which allows the censure or recall of an elected representative. “So once the voter has cast his vote, it is pretty much in the hands of the MLA or the MP to do what he feels like, which is more often than not: feather his own nest. The RPA has a provision for disqualification of elected representative if he is convicted under any of the scheduled offences. But this provision does not extend to considering ‘cheating the electorate’ after securing their vote a criminal offence.”

However, Section 405, IPC, says: “Whoever, being in any manner entrusted with property, or with any dominion over property, dishonestly misappropriates or converts to his own use that property, or dishonestly uses or disposes off that property in violation of any direction of law prescribing the mode in which such trust is to be discharged, or of any legal contract, express or implied, which he has made touching the discharge of such trust, or willfully suffers any other person so to do, commits criminal breach of trust.”

The crucial requirement of the Section, our cover story points out, are “entrustment whether express or implied” and “property”. Should the courts consider the position of elected representative “property” and vote an entrustment of that property to an individual? Especially in the light of the fact that turncoat MLAs are usually rewarded with some public office by the ruling party. Should that reward be regarded as “consideration” for disposal of the entrusted property? Either the court or the Election Commission will have to delve into it.

Should crossing the fence, he asks, then be considered an offence under the sections related to cheating and befooling a person under the IPC. No electorate has so far tried to register an offence against its own representative under any of the sections of the IPC so courts have not had the opportunity to rule on it.

It may well be worth it. It may also be worth exploring The Right to Recall, the widely acclaimed Swiss imitative of right to recall an elected representative if at least 25 percent of the electorate did not like his work. This is now gaining currency around the world. In 2016, says Mishra, BJP MP Varun Gandhi had presented a Private Member’s Bill in Parliament focusing on the need for right to recall. It did not find support even within his own party’s ranks. Once elected, no one wants to be recalled but they want to continue dodging their own voters with dubious statements to support their undemocratic decisions.

We ask: Can the courts find a mid way?

Lead illustration: Amitava Sen