Above: Nusli Wadia (left) was an independent director of the Tata group, and Cyrus Mistry (right) former chairman of the Tata group

An analysis of the provisions of the Companies Act, 2013, and of Clause 49 of SEBI’s Listing Agreement shows that these directors do not really have freedom

~By Mukesh Kacker

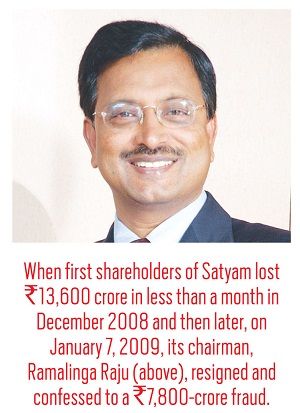

It was L’affaire Satyam in 2009 which brought words like “corporate governance” and “independent directors” to national prominence though they had been part of the corporate lexicon for some time. When first shareholders of Satyam lost Rs 13,600 crore in less than a month in December 2008 and then later, on January 7, 2009, its chairman, Ramalingam Raju, resigned and confessed to a Rs 7,800-crore accounting fraud, the spotlight was firmly focused on its high-profile independent directors who included a Harvard Business School professor and a former cabinet secretary.

What was till then known in corporate India but never acknowledged openly became an open secret—that independent directors on the boards of listed companies were hardly independent and just endorsed every proposal brought in by the dominant shareholder or promoter without any questions or due diligence. It triggered a national debate on corporate governance standards and on the role of independent directors. It led to a revamped Companies Act, 2013, which tried to enforce rigorous corporate governance standards and defined the role of independent directors. In order to align its own provisions with this revamped Act and to make the corporate governance framework more effective, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) also amended Clause 49 of the Equity Listing Agreement in 2014.

Legislation has not been able to fix either corporate governance or the independence of independent directors and major corporate controversies involving these two issues are brought to the fore from time to time—the grounding of Kingfisher Airlines, the Tata vs Mistry battle and the Infosys imbroglio being the major ones. That the system is still broken was recently admitted by Ajay Tyagi, the new chief of SEBI, who said in April 2017 that independent directors were not really independent. Though there is a clear link between the three pillars—corporate governance norms, role of independent directors and their independence—I will only examine the last issue. What constitutes “independence” and why are independent directors not “independent” as reportedly admitted by the SEBI chief?

Speaking of independence, first there are traits and qualities that come within the realm of personality and psychology of an individual—ethics, commitment to fairness, self-esteem and a desire of being faithful to the post one occupies. These cannot be legislated. Many commentators have said that nothing can be done to enforce independence because it comes from within. But surely we are not talking about this aspect of independence here. We are primarily concerned with what can be legislated and enforced, namely, the independence from the dominant shareholder or promoter so that the independent director doesn’t feel beholden to him.

It can be safely assumed that independence of thought, action and decision-making in all positions of higher responsibilities is a function of three factors—process of appointment, process of removal and monetary compensation. The judiciary in India is independent because all three factors are largely independent of the executive. The higher civil services in India were also meant to be independent of the political executive and the processes of their appointment and removal and their salary are insulated from the political executive, though the same cannot be said about their transfers and promotions which have become reasons for the loss of their independence. In the case of independent directors in listed companies, if these three factors can be kept insulated from the dominant shareholder, then we will have a beneficial environment for independence. Let us see whether the Companies Act, 2013, and SEBI’s Listing Agreement have been able to create such an environment.

Section 149 (6) of the Companies Act, 2013, lays down that an independent director is a person of integrity, possesses expertise, and is not related to promoters or directors in the company.

Section 149 (6) of the Companies Act, 2013, lays down the essential requirements for being an independent director. It says that an independent director means a director who, in the opinion of the board, is a person of integrity, possesses relevant expertise and experience, is not related to promoters or directors in the company and who has or had no pecuniary relationship with the company or with its promoters and directors. It then goes on to expand the definition of “no past or present pecuniary relationship”. Section 49 of SEBI’s Listing Agreement also mirrors these essential requirements. These are pretty exhaustive and I find them sound in terms of vetting the past and present credentials of a prospective independent director.

FRAUGHT PROCESS

The devil lies in the process of appointment. Clause 49 of the Listing Agreement lays down that the Nomination and Remuneration Committee of the board will formulate “the criteria for determining qualifications, positive attributes and independence of a director” and will identify and recommend to the board their appointment. The board then approves or disapproves the recommendations made and takes them to a general meeting of the company for final approval.

Section 152(2) of the Companies Act lays down that every director shall be appointed by the company in a general meeting. Now, how does the Nomination and Remuneration Committee select an independent director? The fact is it does not! It only identifies and “nominates” and, expectedly, it can only nominate people known to or close to the promoter or other directors. Although this committee is headed by an independent director, it is easy to see that only those who are close to the promoter and trusted by him have a chance of first being nominated by the committee and then being approved by the board and shareholders. Directorship in listed companies, therefore, remains a closed and incestuous group. It is nobody’s case that the persons nominated are not deserving or meritorious. The issue is that those appointed know very well that they owe their appointment to the promoter and will therefore hesitate to disagree with him. It is felt that there should be a statutory body to “select” independent directors and the board of a company and its shareholders should not be able to reject the selection without a grave cause.

What about removal? Is that insulated from the dominant director? Under Section 115 of the Companies Act, 2013, shareholders can give a special notice to move a resolution. Under Section 100, shareholders collectively owning 10 percent of paid-up equity can call for an EGM. Section 169 says that any director can be removed by passing an ordinary resolution at a general meeting. It makes no distinction between an “independent” or “non-independent” director.

Thus, all that it takes to remove an independent director is to give a special notice to move a resolution, then call for an EGM and then pass that resolution. Since most Indian promoters have large shareholdings in their company (more than 10 percent), removal of an independent director at their behest is not merely a possibility but a reality. This was recently played out in the Ratan Tata-Cyrus Mistry spat.

Thus, all that it takes to remove an independent director is to give a special notice to move a resolution, then call for an EGM and then pass that resolution. Since most Indian promoters have large shareholdings in their company (more than 10 percent), removal of an independent director at their behest is not merely a possibility but a reality. This was recently played out in the Ratan Tata-Cyrus Mistry spat.

After Mistry’s removal as chairman of Tata Sons, first the independent directors at Indian Hotels Company came out in support of Mistry. Thereafter, independent directors at Tata Chemicals and at Tata Steel also came out in his support. Tata reacted by alleging that Nusli Wadia, an independent director at these companies, was behind these developments and moved to have him removed from these boards. I am not taking sides with either Mistry/Wadia or Tata on the merits of the spat. I am only concerned at the relative ease with which Tata was able to orchestrate the removal of Wadia. If a person of the stature of Wadia cannot express his disagreement as an independent director, what will be the fate of ordinary independent directors?

ISSUE OF REMUNERATION

Let us now analyse the monetary compensation aspect. The Act of 2013 and Clause 49 of the Listing Agreement are both right in prohibiting any kind of business or pecuniary relationship between the independent director and the company. On remuneration, Sections 149(9), 197(5) and 197(9) of the Companies Act, 2013, prescribe that independent directors can be paid a sitting fee and related reimbursements for attending the board/committee meetings and profit-related commissions as approved by the members. This is the problematic part. It is easy to see that for profit-related commissions, the proposal has to start in the board and then has to be taken to a general meeting for approval by shareholders; the process must be blessed by the dominant shareholder and must strike at the very roots of the “independence” of directors.

If on the other hand, an independent director is paid yearly remuneration as mandated by either statute or rule, then he has no reason to feel grateful to the promoter. At present, over 90 percent of the companies do not pay profit-related commissions to independent directors, while many of the top companies pay huge commissions. Both practices are wrong. Independent directors have been entrusted with huge responsibilities and it is only fair to give them proper remuneration. This should be mandated by statute or rule and should not be dependent on the largesse of the promoter.

It would have been great if the panel on corporate governance under Uday Kotak-led SEBI panel had deliberated on these core issues.

It is time the MCA and SEBI took note of the issues raised in this article and plugged the loopholes.