The glacial pace of action increasingly imperils both judicial independence and the constitutional republic

~By Upendra Baxi

There has been more heat than light over the motion initiated by individual members of seven opposition parties regarding removal proceedings against Chief Justice of India (CJI) Dipak Misra. The motion was moved on April 20, 2018, disallowed by the Rajya Sabha Chair on April 23, 2018, and challenged as arbitrary and unconstitutional by two Congress signatories in the Supreme Court on May 7, 2018. The plea argued that “the impugned order, in a cavalier, cryptic and abrupt manner, shockingly holds that none of the other charges are made out without disclosing as to on what basis this finding was returned”.

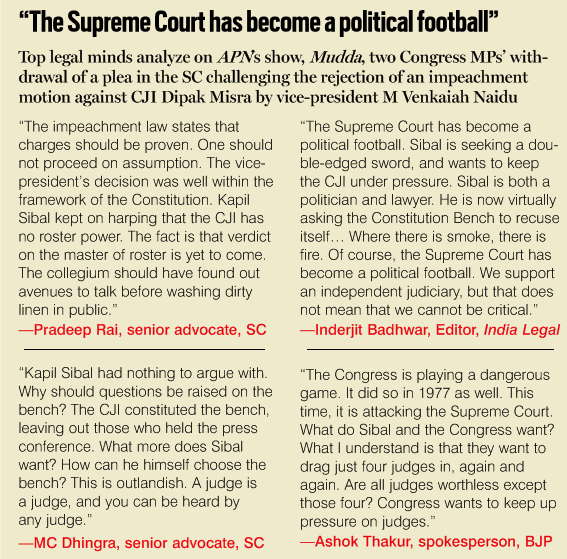

The petition was moved first before the Justice Jasti Chelameswar-led bench which adjourned the hearing till the next day. On May 8, a Constitution Bench was convened, comprising the five seniormost justices (discounting the collegium justices, four of whom had held a press conference on January 12, 2018). The substantive issues before the Bench were never argued as senior advocate Kapil Sibal, who was representing the petitioners, raised a threshold point: How was the order constituting the bench made?

His essential argument was that even when accepting that the CJI is a master of the roster, an order under the rule-making powers prescribes a five-judge bench when a “substantial question of law” (Article 145) is involved. The order making such a determination should be made available; when the Court asked him to proceed on merits, Sibal withdrew the petition, which was then dismissed by the Court as withdrawn. The political economy of speed characterising the motion and its withdrawal/dismissal is indeed amazing; perhaps an equally expeditious judicial decision may also have greeted the decision on merits.

Sibal is entirely right in claiming that a citizen litigant is entitled to know whether the bench was constituted by a judicial order and if necessary, to contest it. And one hopes that the situation is adequately clarified. On the other hand, eminent lawyers have publicly suggested that the argument on merits could have well proceeded, incidentally, also raising a challenge to a judicial order.

If the CJI has the power to constitute benches, being the master of the roster, can his order be challenged on the ground of natural justice whose venerable and valuable maxim is that no person shall be a judge in her cause? Can one object to a bench of five other seniormost non-collegium justices, other than the four who had taken part in a press conference on January 12, 2018?

Surely, it is unworthy to suggest that the CJI passed any substantive instructions in his own favour. And it is contemptuous to say that the five-judge bench will not decide in accordance with its constitutional duties.

The situation warrants comparison with judicial recusal. Recusal was ordinarily granted when the counsel mentioned that a judge should not hear a matter; often, a judge would recuse herself on the ground of conflict of interest and propriety. But in Subrata Roy Sahara (2014), Justice JS Khehar (speaking also for Justice Radhakrishnan) ruled that while recusal is an appropriate remedy when pecuniary bias is demonstrated, there is a general Third Schedule constitutional duty to adjudge all cases and controversies coming before the Supreme Court without “fear and favour”.

Thus, a constitutional convention was made subject to judicial review process and power. In the 2016 NJAC case, Justices Chelameswar and Adarsh Kumar Goel even added that a recusal would fall foul of the oath under the Third Schedule to do justice without fear or favour. Their Lordships further referred to the “doctrine of necessity”, a doctrine resting on the idea that necessity knows no law. This is very sparingly used to validate extra-legal/unconstitutional acts by state authorities.

Its contemporary usage first occurred in a dubious Pakistan decision by Chief Justice Muhammad Munir in 1954 where he invoked the maxim of a medieval British jurist, Henry de Bracton, which said “that which is otherwise not lawful is made lawful by necessity”.

What remains to be debated is the extension of this doctrine in situations suggesting an official bias to all justices (say in matters of judicial appointments, transfer of high court justices or other matters concerning the judicial collegium). At the same time, if all justices were to recuse, who then will decide the matter? This was not a “result” legally permitted, their Lordships ruled, by the “doctrine of necessity”.

Similarly, the mere motion of removal does not deprive the CJI of his functions as a master of rolls. Nor does the Constitution require a chief justice (or any justice) to stand down during the removal proceedings. Nor does any question of propriety even arise when the allegations against a justice are held not to have been made out by the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha or the Speaker of the House. Any change in the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, which blueprints the procedures to be followed in an inquiry for “proven misconduct” against a judge would have now to run the gauntlet of the basic structure doctrine as developed by the Supreme Court.

One hopes that this politics of judicial embarrassment will now cease, given that the incumbent CJI retires on October 2 and any proceedings for removal thereby become infructuous. Among the urgent issues that remain are the expeditious finalisation of the Court-approved Memorandum of Procedure, quick moves in filling all judicial vacancies, and a sorely needed workforce expansion of judicial services. The glacial pace of action increasingly imperils both judicial independence and the constitutional republic. What Justice Arun Mishra remarked from the Bench as recently as May 10 is that not merely daily media “discussion of court proceedings is happening” but that “every judge is targeted”. However, destruction of “this institution” may also mean, he said, that “you people won’t survive….” Modern history archives that the shining knights of accountability may also be the unwitting pioneers of destruction of residual institutional autonomy.

—The author is an international law scholar, an acclaimed teacher and a well-known writer