The Women and Child Development Ministry has recently framed draft guidelines for juvenile shelters. However, these do little justice to key issues and merely go over old ground, say child rights advocates

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

In the summer of 2007, national television ran the story of an eight-year-old boy from Begusarai in Bihar who committed the murders of his eight-month-old sister, six-month-old cousin and another baby girl who lived in the same village. During the telecast, the camera avoided the boy, but showed the village children running away in terror from him even as he was led away for presentation before the nearest juvenile justice board. When asked details of the crimes committed, the boy kept evading the queries by putting on a broad smile and asking for biscuits and candies.

Is this child a sadist? Does he deserve empathy and an opportunity to be rehabilitated in a special home and then into mainstream society, which is the basic principle of restorative justice? At another level, does he understand the full impact of what he has done? If not, once he does, how will he deal with the resulting emotions and come to terms with the consequences?

Following a Supreme Court directive on February 2, 2016, during the proceedings of a 2013 case regarding inhumane conditions in 1,382 prisons, the women and child development (WCD) ministry came out with a 287-page draft manual of guidelines on the care and upkeep of children in conflict with the law who are in observation homes, special homes and places of safety across the country. The guidelines aim to protect the inmates from neglect, exploitation and sexual abuse at the hands of the home staff.

Following a Supreme Court directive on February 2, 2016, during the proceedings of a 2013 case regarding inhumane conditions in 1,382 prisons, the women and child development (WCD) ministry came out with a 287-page draft manual of guidelines on the care and upkeep of children in conflict with the law who are in observation homes, special homes and places of safety across the country. The guidelines aim to protect the inmates from neglect, exploitation and sexual abuse at the hands of the home staff.

The guidelines are explicit in certain areas. For instance, it stipulates the staff not to “kiss, fondle or sleep alone with the children,” “touch a child in an inappropriate or culturally insensitive way,” “use corporal punishment or tolerate corporal punishment by the staff,” “give cash or gifts directly to children” and “engage children in personal work or employ them at work or at home.” Child rights advocates point out that these provisions address limited concerns and, as a result, miss out key points.

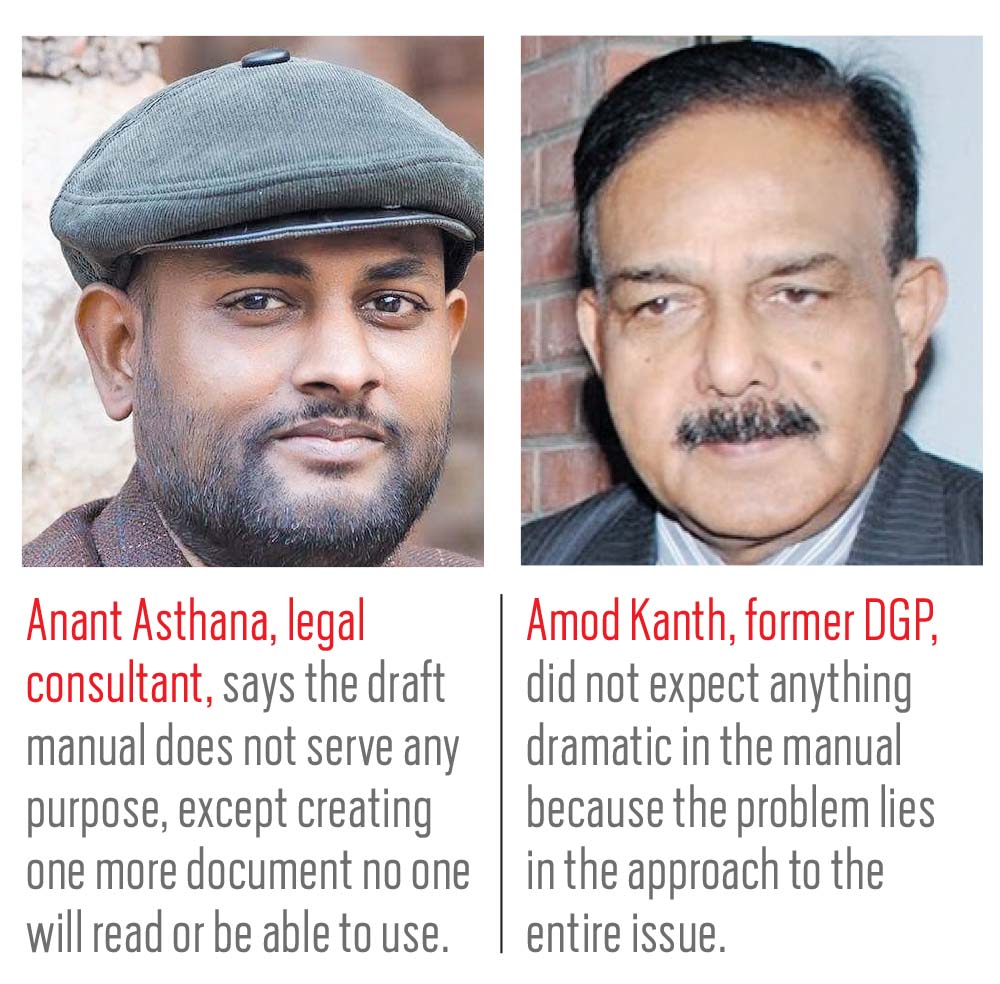

SERVING NO PURPOSE

Both legal consultant Anant Asthana and social activist and founder of NGO Prayas, Amod Kanth, agree that the manual does not contain anything new. “It is nothing like a Model Prison Manual, as envisaged, but a rather erratic cut-copy-paste job, a verbose document containing various provisions of Juvenile Justice Rules 2016, Juvenile Justice Rules 2007 and Juvenile Justice Act 2015 loaded with a lot of content on theory and principles, with some chapters on ‘Child Protection Policy,’ ‘After Care’ and ‘Monitoring Authority’ awkwardly inserted,” says Asthana to India Legal. “What needed to be done was to provide clear legal provisions on details which are required and not addressed in the Act & Rules, which this document does not do at all. This document does not serve any purpose, except creating one more document which no one will read and no one will be able to use,” he avers.

He goes on to point out lacunae in the manual. For a first, there is no mention of what documents or identification is required for parents and relatives who come to meet the children. This is crucial to address as often members of street gangs come posing as kin. Then, there is no detailing of how a record needs to be kept to ensure that children receive the money they earn working in kitchens and other places in child care institutions at the time of their release. The Rules 2016 provide a monetary incentive to children who show good behaviour.

Apart from this, there is no attempt to lay down a mechanism for setting up of drug de-addiction facilities, which is a massive problem among teenagers (Section 93 of the latest Act makes a reference to it). And then, there is the constant tussle between Legal Aid lawyers and the staff at the homes. The lawyers say they need greater access to deal with cases effectively.

Child rights advocates argue that the draft manual is silent on the handling of transgender children, the disabled and pregnant girls. It only mandates that a pregnancy or other tests be carried out on victims of sexual offences only in the case of an order by the juvenile justice board or a juvenile court.

In case of delayed birth registration of juvenile offenders, the Act puts the responsibility on the childcare institution, says Asthana. But details like who will fill up application forms and who will pay the fees are not available, he highlights, adding that if a child needs to be represented in higher courts, the question of who will be responsible for signing the vakalatnama on their behalf has not been clarified.

According to the latest JJ Act, an observation home houses the children during the inquiry, the shelter homes keep those who are pronounced offenders, while places of safety have both categories of children as well as adults. This is because under the JJ Act 2015, juveniles between 16 and 18 years of age, who are found guilty of committing heinous offences through a preliminary inquiry by the Juvenile Justice Board, will be sent to a children’s court that can pronounce the child guilty. Such juveniles can be detained in the place of safety until they reach the age of 21. Asthana points out that the manual does not provide adequate guidance on how to ensure segregation of children and adults in this institution.

“In most Juvenile Justice Boards (JJBs), there is an institution called Khariza,” says Asthana. “In Delhi, one can go to any JJB and find this institution. The JJ Act and Rules do not recognise this institution but it is very much required. When children are brought from observation homes or special homes or places of safety to be produced before the JJB on a given day, they are kept in this institution. It is managed and run by the 3rd Battalion of the Delhi Armed Police who escort them to and from the hearings. And whenever such children’s cases are called, officers of the 3rd Battalion take them out and bring them before the JJB and after the hearing is concluded, they are taken back to the Khariza. In the evening, a bus comes and takes these boys back to their respective institutions.” There is no mention of the Khariza in the guidelines.

DIVERGENT APPROACHES

India Legal visited the special home for boys at Majnu Ka Tila, one of the two such institutions in the capital. It was the place that housed the Jyoti Singh aka Nirbhaya rapist and currently lodges the 2015 Karkardooma court firing accused as well as the youngster involved in the 2016 Mercedes hit-and-run case. Superintendent Ramvir Singh said the complex, which has a place of safety, a shelter home and an observation home, has a total of 62 children, of whom 30 live in the special home. “We feed them and take care of their needs. However, it is hard sometimes, when they abuse you or gang up against you,” he said. Asked about success stories, he said there is a 99 percent chance of reform for kids who come in for statutory rape (sex with a minor). “These are a result of a romantic relationship to which the girl’s family had objections and simply used the law as a weapon to break up the relationship,” he said.

Former DGP of Goa and Arunachal Pradesh, Kanth, who runs Prayas Juvenile Aid Centre Society that manages the 20-year-old observation home at Feroz Shah Kotla which has over the years housed 12,500 plus juveniles, gives a very positive outlook. He says that half of the staff lives in the home with the children, sharing the same food.

Kanth also expresses his views on the new JJ Act that allows juveniles between the ages of 16 and 18 years to be tried as adults for heinous crimes. “I strongly opposed placing them under the purview of the criminal justice system both in the Salil Bali vs Union of India (2013) and the Dr Subramanian Swamy And Ors vs Raju Thr. Member Juvenile Justice Board (2014).” The second case pertains to the infamous Nirbhaya rape.

Regarding the draft manual, Kanth feels “there is nothing great about it. Frankly, I did not expect anything dramatic in it.” This is because the problem lies in the approach to the issue. Citing the statistic that the total number of juvenile crimes is less than one percent of crime in the country, Kanth says that of them, the number of heinous crimes is about 4,000-5,000. “Are we such a wretched country that we can’t look after 5,000 children?” he asks.

After missing several deadlines, when the ministry placed the draft of the manual before the apex court on May 5, the court directed: “The manual should be circulated to all the state governments/union territories expeditiously so that the suggestions and recommendations incorporated therein can be implemented, if necessary with state-specific modifications.”

“I have seen the document placed by the ministry on its website. However, state-specific modifications as suggested by the Supreme Court are not there in the document. I don’t think suggestions and recommendations given by various state governments have been included in it,” says Asthana.

When India Legal News contacted the WCD ministry, deputy secretary Ashi Kapoor said the department is working on the guidelines. The Supreme Court is scheduled to hear the case on August 10. It is hoped that the feedback from the states will be incorporated by then and the revised document presented before the court.